It is a dark and rainy night in the coastal waters of the Philippines. Sea wardens—community fishers trained by the local government to monitor the marine protected areas—flag a commercial fishing vessel found within municipal waters where they are prohibited.

The wardens inform the wayward boat over radio of their violation of entering municipal waters where only small-scale fishermen are permitted. The violators ask for proof of their transgression such as a photo or a record of coordinates, but when the wardens cannot produce any, there is no choice but to let the offenders go.

Indonesian sea wardens face a similar scenario, this time with a commercial boat operating within a marine protected area (MPA), where human activity is restricted to conserve the fragile habitat beneath it.

The fisheries sector is known for practices devastating to marine life through illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, and perpetrators are seldom prosecuted.

Athough all large vessels at sea are required to have satellite-based technology like the Automatic Identification System (AIS) and vessel monitoring system (VMS) that allow authorities to monitor their location, most vessels switch off their devices, which might indicate some suspicious and potential illicit activities, says Arifsyah Nasution, regional oceans campaign lead of Greenpeace Southeast Asia.

“Strengthening the capacity of sea wardens at the local level in adopting and using applicable modern technology at the field levels will help national governments perform more effective efforts against illegal activites that can not be resolved alone with AIS and VMS requirements,” Nasution tells Eco-Business.

Since 2020, a growing number of nations have pledged to protect and conserve at least 30 per cent of the ocean in a movement dubbed “30 x 30”: 30 per cent by 2030. This is equivalent to safeguarding 109 million square kilometres, an area almost 12 times the size of the United States.

Emerging technologies are proving increasingly helpful in monitoring abuses at sea and enforcing existing laws, and will become critical tools as more of the ocean comes under protection. Some of these include: an artificial intelligence-enabled device that ensures sustainable practices on boats in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, a low-cost vessel monitoring tool for small-scale fishermen in the Philippines, a spatial monitoring tool that tracks illegal fishing in Raja Ampat, a satellite-based reef monitoring system that recognises coral bleaching, and a device that detects fish blasting in real time in Sabah.

Eco-Business explores this rapidly growing array of cutting-edge technologies that are helping to manage the ocean’s delicate ecosystems.

Snaring illegal fishing and forced labour through Artifical Intelligence

Tuna fisheries are under severe threat from IUU fishing, due in part to a widespread failure to tackle the issue that has left nearly 90 per cent of global fish stocks exploited or depleted, according to a United Nations’ study.

The industry is reliant on human observers to monitor such activities, but they often face intimidation and harassment, resulting in many boats going unobserved. Inspections have also dropped due to the Covid-19 pandemic with authorities suspending requirements for on-board observers to contain the spread of the virus.

The absence of human observers on board is “worrying” but it is what electronic monitoring data hopes to remedy, says Mark Zimring, largescale fisheries director of US-based environmental organisation, The Nature Conservancy.

A human observer makes notes on the tuna catch in a vessel in the Western Pacific Ocean. Image: The Nature Conservancy

Together with his team, Zimring developed FishFace, a system which has electronic monitoring installed on video cameras onboard, that use facial recognition to gather fisheries data like recognising species, measurements and seafood traceability.

Data from the cameras are transmitted to the monitoring office instantly, so that it can be used to make management decisions more quickly. The traditional way of checking the data is by accessing hard drives of vessels that may be at sea for up to six months, costing time and money that imperiled global fisheries do not have.

“Using early phase artificial intelligence tools, the system is able to automatically identify when activites are ocurring on deck and records what is happening. As AI tools advance, it is hoped that they will accelerate and largely automate electronic monitoring data review,” said Zimring.

Apart from illegal fishing, human rights abuses are rampant in the seafood sector.

Thai Union Group, the world’s largest canned tuna producer, was embroiled in a labour scandal six years ago, where employees were reportedly working under dire conditions.

An Associated Press investigation in 2015 found that children were forced to work for little or no pay peeling shrimp which ended up in the supply chains of American brands like Chicken of the Sea, and on major retailers’ shelves, including Wal-Mart, Kroger and Whole Foods.

Since then, Thai Union has taken steps to address forced labour risks across its supply chain, including implementing FishFace’s AI technology to oversee possible unethical and human rights abuses aboard its tuna vessels.

Zimring notes: “Often times, fishers may not know or understand the rules and may operate with a sense of impunity because of lax historical enforcement. But tools like electronic monitoring make fishers and fishing companies partners in driving sustainable fisheries and, of course, creating consequences for those that don’t improve their operations.”

Cost-efficient vessel monitoring systems for Filipino small fisherfolk

With the Philippines losing up to US$1.3 billion from IUU a year, the government’s amendment in October 2020 of its fisheries code to require vessel monitoring systems (VMS) in all Philippine-flagged fishing vessels was welcomed by local governments and civil society organisations.

However, VMS devices normally used by commercial vessels can be expensive. One system is priced at about US$2,000, which cash-strapped local government units (LGUs) cannot readily purchase for their small-scale fishermen.

The Parrotfishnet tracker. The location information display shows what municipal waters the vessel in question is in, its exact location (longitude, latitude) and the time it was found. This data can be used as evidence by law enforcers if the vessel was indeed trespassing. Image: Parrotfishnet

This is what inspired Diogenes Pascua and his team of engineers from the Mindanao University of Science and Technology in southern Philippines to design a more cost-effective device targetted for non-industrial fishers, at half the price of a regular VMS.

They came up with the Parrotfishnet system, a portable, solar-powered tracker attached to a fishing vessel, with an interface that uses Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite to detect any intrusion within municipal water, or water 15 kilometres from the coastline, where only small-scale fishers are allowed.

Internet of things (IoT) technology is used to transmit the exact time and locaton of the intruder in real time to the LGU so authorities can monitor and apprehend the violator.

The tracker can only monitor intrusions within an eight-kilometre range, which is why the system comes with a buoy that can extend the coverage beyond its normal range.

“Commerical fishers must be prevented from entering municipal waters. These waters are the most important ecosystem in the sea. It is where the coral reefs and spawning grounds of fish are. This is the importance of guarding the 15 kilometre area. If we empower the small fishers to protect this area, then we sustain our fisheries,” Pascua tells Eco-Business.

For years, commercial fishing vessels have been able to encroach on municipal waters because they bribe small-scale fishers not to report them, Pascua adds.

But today, he said small-scale fishermen have already realised that overfishing by big vessels is destroying their livelihood, reducing their catch from 20 kilogrammes (kg) of fish ten years ago, to only five kg on a good day.

“

Commerical fishers must be prevented from entering municipal waters. If we empower the small fishers to protect this area, then we sustain our fisheries.

Diogenes Pascua, engineer, Parrotfishnet

He also lamented that developing IoT technology to protect waters in Southeast Asia is “non-existent” because the humidity and salinity of the water can be too harsh for the physical hardware.

“This is sad since our region has the peninsular islands and the longest coastlines. There are actually gigantic opportunites in the blue economy. We need more technology to protect our fisheries. They are the most affordable food, accessible to all levels of society,” he says.

Smart phones that locate IUU and overtourism in Raja Ampat

The waters of Raja Ampat in the most eastern island of the Indonesian archipelago, are regarded as having the most biodiverse coral and fish species compared to anywhere else in the world.

But this has also meant that it can be overrun by tourists and prone to increased instances of IUU fishing in its vast marine protected areas of two million hectares.

Conservationists in Raja Ampat have devised a spatial monitoring software installed in smart phones aimed to address these issues.

Shark-finning caught on a boat. The SeaTracker interface as seen by MPA authorities from their control centre on land shows how patrollers apprehended shark catching and finning, which is prohibited for the protected species. Image: SEA People

Called SeaTracker, the software uses a geographic information system (GIS) that creates a map database to track IUU and tourism load as they happen over time in a specific location within a protected area.

“Ranger patrols in the field have been trained to use the SeaTracker software installed in their smart phones which they use to take photographs of the offending fishing vessel and immediately upload them to an enforcement database through the cellular network,” says Arnaud Brival, a marine ecologist who helped design the software.

SeaTracker provides both time and date, geo-location, a description and photos of activities, all of which can be used to support management decisions and used as legal evidence, he adds.

Ranger patrols from the field send information to MPA authorities through SeaTracker software installed in their smart phones. Image: SEA People

Although the system comes at a hefty US$3,000 per year for each of Raja Ampat Marine Park’s 50 patrollers, Brival noted that their GIS supplier slashed the unit cost for them by 90 per cent to support the group’s advocacy.

“

Technology is not a magic bullet that can solve all human vices causing IUU and overtourism.

Arnaud Brival, marine ecologist, SeaTracker

Since the software was deployed in West Papua’s waters in March, rangers have flagged 13 violations, regardless of pandemic lockdowns. Incidents ranged from fishers in the wrong zones, catching of protected species, and for tourists, the lack of documentation.

Despite the system’s promise, Brival says: “Technology is not a magic bullet that can solve all human vices [causing IUU and overtourism]. It will remove human error out of the equation but we still need the cooperation of community-based patrol and management to better address the issues.”

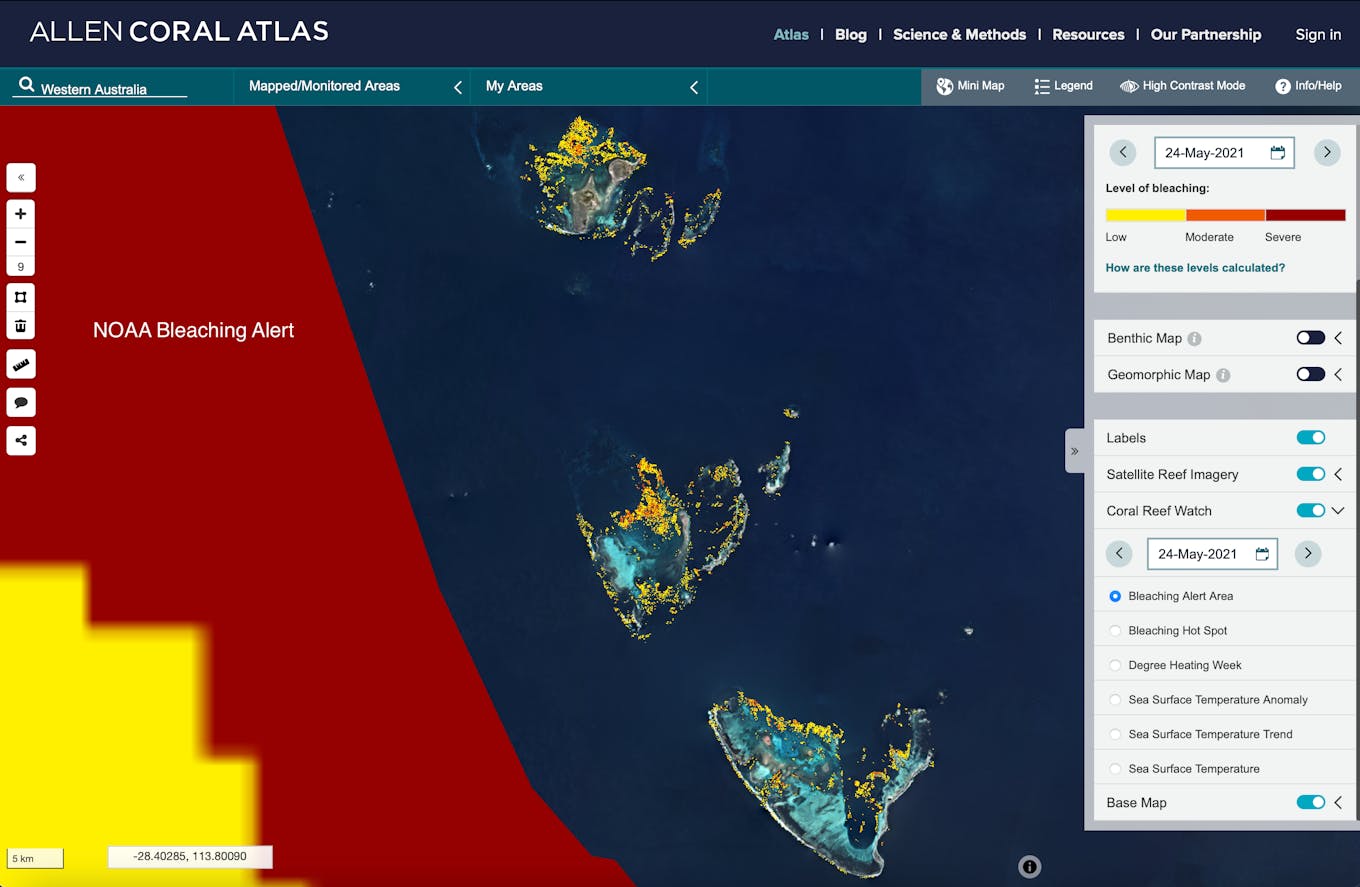

Satellite-based reef monitoring system that tracks coral bleaching

With rising sea surface temperatures driving more frequent coral bleaching around the globe, studies have predicted that few healthy coral reefs will remain in tropical oceans in the next century.

Scientists from Arizona State University in the US and satellite company Planet developed a new tool that could reveal the full extent of bleaching worldwide and the spots where corals are surviving.

The Atlas monitoring system allows users to see where corals are bleaching at a global scale every 15 days in order to concentrate efforts in those specific areas, says Brianna Bambic, programme manager at the Allen Coral Atlas, which launched the tool in May.

Satellite images from the monitoring system show different levels of bleaching happening around the Western Australian islands. The yellow colour identifies a low level of coral bleaching while red indicates severe bleaching. Image: Allen Coral Atlas

Using satellite imagery, the tool archives daily images of coral reefs mapped by the University of Queensland, Australia. By comparing different sets of images of coral reefs before they bleach, the tool is able to detect the dramatic colour changes that are characteristic of coral bleaching.

It detects variations in reef brightness using high-resolution satellite imagery powered by an advanced algorithm indicating whether reefs are under stress caused by marine heatwaves.

“The Atlas mapping tool can also be helpful for marine spatial planning objectives, such as the United Nations’ initiative to reach 30 per cent of coral reefs protected by 2030. With the entire Asian region mapped, now countries are able to compare region by region to reach their conservation and sustainability goals,” Bambic says.

Stopping fish blasts in real time in Sabah

Lockdowns associated with the Covid-19 pandemic last year abruptly cut tourism in Malaysia’s diving hotspot Sabah, shutting off its main source of income and increasing food insecurity for local communities.

The effects of the pandemic have put a lot of pressure on fishermen and their livelihoods which has resulted in the resurgence of fish bombing in the area, says Terence Lim, executive director of non-governmental organisation Stop Fish Bombing Malaysia.

Fish bombing is an easy but destructive method of catching fish, where a handmade bomb, usually made of kerosene, fertiliser and a hand-fuse, is thrown into the sea, yielding up to 45 kg of fish. The explosion kills or stuns fish, which are then scooped out of the water. It is also known as blast or dynamite fishing.

A blast detector on the seabed in the waters of Sabah. Image: Stop Fish Bombing Malaysia

In 2015, Lim developed a detection system which could trace explosions beneath water surface from a distance of up to 25 kilometres away. He partnered with ShotSpotter, a US-based company that uses sensors to detect gunshots in American cities, to design an electronics tool housed in a case and hydrophones to recognise and triangulate fish bombing blasts in Sabah. Unlike other sensors, the device can pinpoint the location of the blast in real time using GPS, notifying the nearest enforcement to respond.

Although there are some reports that the number of fish bombs has decreased this year, Lim says it is possible that the blasting activity might have moved to another location out of the range of their sensors.

This is why the veteran environmentalist and diver is in the midst of raising funds to deploy 250 more underwater bomb detection sensors throughout Sabah’s coastal waters, noting that with only 12 detectors last year, with the help of the tool, Sabah Parks was able to charge five people in two fish bombing cases off Tunku Abdul Rahman marine park.

Lim tells Eco-Business: “For years there were no real-time location detection technology for detecting fish bombing activities and the fish bombers have managed to get away with it. Our goal is for this technology to be used to protect the reef and marine ecology and deter any fish bombing activities as we now can detect them in real-time.”

Technology is not enough?

Despite the emergence of new technology, IUU is still rampant in the region due to lack of responsive inspections and law enforcement, Greenpeace’s Nasution tells Eco-Business.

“With new technology, officials can use it in real-time to strengthen at-sea and at-port inspections, as [well as] during the prosecution process once all initial basic evidence is collected and confirmed. But we don’t close our eyes and minds to the suggestion that unresponsiveness in law enforcement could be an indication of corrupt practices,” he says.

Nasution, also a delegate to the UN Ocean Treaty, highlights the application of the fisheries transparency principles as a mechanism to help curb illegal activities in the fisheries sector.

The principles fall under the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI), a global multi-stakeholder partnership that defines what fisheries information governments should publish online. It has set out a framework that sets clear requirements on what is expected from countries regarding transparency in marine fisheries.

The Republic of Seychelles was the world’s first country to submit its report to FiTI in April.

The Indonesian ocean advocate also underscores how governments in developing regions are often left no choice but to prioritise basic public service expenditures like health, basic education and other land-based infrastructure over conducting effective monitoring controlling and surveillence with modern technology.

He urges national governments to empower local-coastal fishers communities and sea warders in the field level by financing more pilot projects that apply modern technology and solutions at community-levels.

“There must also be strong international community cooperation that includes public-private and technology-enterprises collaboration in allocating grant-budget, providing access to satellite-based information platforms and training for local community and sea wardens in adopting those new technologies,” he adds.