The orange pop of colour from the ‘sashimi’ sitting on granite slate has all the bearings of raw salmon. Wrapped in a neat coil and topped with delicate sea grapes, the waxy texture tears like ribbons of salmon. But this is no ordinary sashimi. It is in fact, carrot.

While creative chefs like Huang Yen Kun at Joie, a high-end vegetarian restaurant in Singapore, challenge the norms for vegetable dishes, other innovations in producing seafood alternatives range from plant-based tuna to aquatic species being developed in labs.

Innovation in this area is, in part, being driven by the soaring demand for seafood and the depletion of wild-fish stocks caused by overfishing. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) reckons that 90 per cent of global fish stocks are either overfished or fished to maximum sustainable levels.

The skyrocketing demand for fish is taking a huge toll on the ocean. Industrial fishing is dogged with allegations of human trafficking and slave labour, unintended killing of more vulnerable sea-life through bycatch and the overall degradation of ocean habitats.

Fears of mercury consumption, shellfish allergies and the injestion of microplastics has triggered some behavioural change. Recent media reports exposing the mislabelling of fish products and seafood fraud have also pushed some consumers towards fish-free products.

Studies have found “creatively labelled” aquatic species where wild-caught Atlantic salmon were replaced with poorer cousins from the Pacific. Prawn balls in Singapore have been found to contain pork and, allegedly, some tuna sandwiches from Subway – the world’s largest sandwich chain - didn’t contain tuna. The fast-food chain recently launched a website defending its sandwich.

Promise and peril of aquaculture

The rise of “sustainable” foods is increasingly touted as a way of curbing soaring global food production and consumption but it isn’t what it seems. The farming of fish and other marine species, known as aquaculture, was originally pegged as the more sustainable way to consume fish, relieving pressure on the depleted ocean while meeting rising demand for seafood.

It is a big business with the global market projected to reach US$376 billion by 2025, according to a report by Changing Markets Foundation, published in July.

While aquaculture and some aspects of fishing have proved to limit the impacts on the environment, it is still far from being a sustainable sector. The aquaculture industry is “exposed to numerous risks” relating to the use of wild-caught fish in feed and the high levels of mortalities, which stem from poor fish welfare, the report says.

A fish farm in Thailand. Aquaculture is the fastest-growing source of protein today. Image: Shutterstock

Very few of the industry’s biggest investors are taking issues of fish mortality and wild-caught fish for feedstock in aquaculture into their engagements, the foundation discovered. Meanwhile, an appetite to finance the sector has seen a scramble of investors subscribe to green bonds for aquaculture which totals US$814 million.

“However, none of the companies appear to be using green-bond proceeds to take meaningful action on the sustainability issues relating to wild-caught fish in feed,” the reports notes.

Fish without the catch

Shiok Meats shrimp dumplings. Image: Shiok Meats

As more people develop an awareness of the trappings of modern-day fishing and sustainability labels come under greater scrutiny, food tech firms hope fishless alternatives will catch up with fake meat’s share of the market in the next decade.

Plant-based seafood is well poised to capitalise on the momentum of the broader plant-based industry, according to the Good Food Institute (GFI), a global network of non-profits that promote alternative proteins in Asia and beyond.

Innovation in food science is paving the way for consumers looking for a product with a resemblance as close to meat and fish as possible without the environmental footprint.

Eat Just, a San Francisco titan in alternative protein, made world history in December when its cultivated chicken — which is produced directly from cells — secured regulatory approval for sale in Singapore.

Well-heeled diners can enjoy this marvel at JW Marriott Singapore South Beach’s Cantonese restaurant Madame Fan. The approval put the Asia Pacific at the “leading edge as an architect of novel and progressive oversight of cultivated meat,” the GFI stated in a recent report.

Now, Singapore-based start-up Shiok Meats is racing to bring to market cultivated seafood. Currently, it is the first in the world to use cellular agriculture technology to produce crustaceans like shrimps, crabs and lobsters.

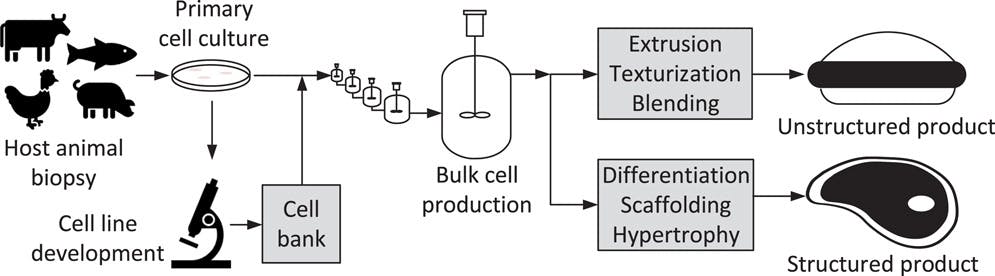

A needle biopsy’s worth of muscle cells is extracted from a single live animal. The cells are cultivated in a bioreactor tank and fed a cocktail of liquid nutrients that help convert cells into muscle, fat and connective tissue. Sheets of muscle tissue can be cut into filets or ground for ‘seafood’ dishes. Unlike the real thing, this lab grown wizardry will not produce the eyes, legs and heads.

Branding a complex product such as cultivated seafood with connotations of a laboratory is a challenge. “Social licensing is key to acceptance,” says Paul Teng, adjunct senior fellow, Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies, RSIS, NTU Singapore. “If you want to convince people, how do you craft the messages?”

Consumers will have to get their heads around a plethora of new terms like ‘cultivated seafood’, ‘clean seafood’, ‘cellular aquaculture’ and ‘cell-based fish’.

“We are cautious with the nomenclature and narrative around cultured/cell-based meat and seafood,” says Dr Sandhya Sriram, chief executive and co-founder of Shiok Meats who believes that the term “lab-grown” is inaccurate.

“As we grow into a key ‘food’ category, our facilities will be above and beyond labs – just like food processing facilities. This way, we help prospective customers make informed decisions about their food choices in a simple, honest, and authentic way.”

Conceptual cultured meat production process. Source: D. Humbird. (2021) Scale-up economics for cultured meat. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 3239-3250.

The innovation has piqued the interest of venture capitalists who are lured by the significant opportunity alternative seafood presents. Impact investors and family offices are also participating in the alternative seafood sector to contribute to conservation efforts, while delivering financial returns.

The first half of 2021 saw record investments with more than US$250 million piled into cultivated-meat startups, according to Bloomberg. The number of companies that have “publicly announced a business line in cultivated meat” stood at 40 by the end of 2020, versus five in 2015, GFI added in its report. Even processed-food behemoth, Nestlé, is jostling for a place at the table announcing plans in July to explore the nascent industry.

The turning tide of consumer choice is courting the attention of corporates who have the ability to produce plant-based products at mass scale.

In March, Thai Union Group, one of the world’s largest seafood producers which owns the Chicken of the Sea brand, introduced its plant-based line OMG Meat, including crab cakes and fish burgers. Last year, it launched its first vegan product — flaked faux tuna made of soy, pea protein and wheat. The company had previously become the focal point for the international debate around slavery in seafood supply chains in 2015.

“We cannot tackle climate change without taking care of the ocean,” says David Yeung, co-founder of Green Monday and chief executive of OmniFoods, a Hong Kong-based foodtech which launched its vegan meat series in 2018 and recently expanded into seafood.

“Thankfully, the new generation is much more aware of the fact that you cannot consume however much you like — the planet simply does not support that.”

Hooking customers

OmniFoods launched its new range of OmniSeafood in June. Its OmniTuna mimics the taste and texture of real tuna. Image: OmniFoods

Despite getting his products into Michelin-starred restaurants in Hong Kong, Yeung admits that convincing consumers is challenging. “Changing people’s diets is going to be arguably one of the most difficult things,” says Yeung. “Food is a very internal matter, it is an integral part of our daily lives.”

Warnings from plant-based advocates about the pressing environmental threats caused by the fishing industry and health risks for seafood eaters may not be enough to convince price conscious consumers who have entrenched dietary habits, Teng tells Eco-Business.

“There is still an unmet demand in large parts of Asia for animal protein. In other words, many people still want to eat more animal protein if they can afford it. It is tough to convince people to eat modern plant-based protein when they haven’t even satisfied the appetite for animal protein,” Teng says.

Global meat consumption is at an all-time high and is expected to continue growing. In Asia, meat and seafood consumption is projected to rise by 78 per cent by 2050, driven by growing wealth and urbanisation, according to a 2018 study by Asia Research and Engagement.

“Taste, price and convenience of plant-based alternatives will be the biggest drivers of consumer change,” says Jen Lamy, senior manager of the Sustainable Seafood Initiative, GFI.

Cost is still a barrier - for now. Despite clearing critical regulatory red-tape in one market, questions of scale linger over the cultivated meat and seafood industry. The most advanced cultivated seafood companies are still at the taste-testing stage and haven’t yet entered the market. When they do, the products are likely to be too expensive for most.

As the science improves and a growing market share bring efficiencies to scale, the price of cultivated and plant-based seafood will decrease and could, eventually, be less expensive than conventional products from the ocean. “That is when we will see really huge shifts in how people behave,” Lamy believes.

The cost and availability of meat and fish could also see a price crunch. “At some point, the price of meat and seafood will slowly, but surely, creep up. The price is going to hockey-stick because of overpopulation, global warming and the fact we are simply running out of space to grow that much more,” says Eugene Wang, co-founder and CEO of Sophie’s Bionutrients, which develops plant-based protein from microalgae. “People will be forced to look to the alternatives.”

Plant-based crab cakes with microalgae protein flour. Image: Sophie’s Bionutrients.

Emulating the taste and texture of fish while replicating the nutrient-benefits has taken time compared to meat and chicken plant-based recreations. For OmniFoods and others, the challenge has been in reproducing the multiple textures and tastes of fishes that also have the similar nutritional value.

Creating an ambient product with a long shelf life such as tinned tuna is rare on the alternative food market, the company states, but its new OmniTuna mimics the taste and texture of the real thing.

“The texture aspect is tough,” says Wang. Consumers can consume up to 60 different species of fish, compared to a handful of land-based animals, he explains. Wang believes that there will be a shift in consumer expectations that will lead to less emphasis being placed on whether or not a plant-based alternative looks and tastes likes its land- or sea-based original.

“You are what you eat, which is why fishes are so nutritious. So why eat the surrogate? It is not efficient,” Wang says. Produced from the microalgae that fish consume, his protein flours have all the nutritional bearings of aquatic species without the environmental catch.

Despite the inevitable growing pains of this new frontier in food, alternative protein is only going to get bigger as consumers try to minimise their impact on the planet. For Wang, there is no going back for alternative protein. “Sometime down the road, we will become big-time. We will be mainstream.”

Rumah Group, the family office arm of Rumah Foundation, is an investor in some of the entities mentioned in this story.