What if countries in Asia, with their shared wealth of sun, wind and tidal potential, could improve energy security and ramp up renewable energy consumption by sharing clean energy across their borders?

From June to October, Nepal and Bhutan could export large amounts of hydropower to India, where energy demand peaks amid the summer heat. In the drier months, as hydropower production falls, the Himalayan states could then tap into the solar and wind energy generated in India.

In the vast plains of Mongolia, where the sun shines 250 days a year on average, long distance transmission of renewable sources such as wind and solar could under certain conditions lead to lower electricity costs than that generated in China, Japan and South Korea, according to research by the Economic Research Institute of Asean and East Asia.

This would open up new energy markets in the landlocked country and boost economic growth, while allowing its neighbours to benefit from cheaper, cleaner energy.

Closer to the equator in Southeast Asia, cross-border trade in renewable energy would significantly improve electricity access in the region, where an estimated 65 million people currently lack access to electricity due to unreliable energy distribution networks and the growing cost of oil and gas.

In the future, if countries could tap into the renewable energy resources of their neighbours, they could eventually wean off polluting fossil fuels and improve quality of life, said Christopher Len, senior research fellow at the Energy Studies Institute, National University of Singapore.

“The basic idea is that instead of generating energy from fossil fuels which are polluting, renewable energy can be transmitted over long distances anytime via interconnected ultra-high voltage power transmission lines to any location where there is demand,” he said.

“Instead of relying on individual local generating sources, a transnational energy network would enable a more stable supply of clean energy which could be transmitted to whenever there is demand,” Len added. “Such linkages would reduce our current reliance on fossil fuel-based power plants.”

Will Asia’s renewable energy industry go borderless?

If Asia could build an interconnected, diversified energy grid, renewable resource-rich locations could be linked to high energy demand centres. The wide geographical spread of countries with differing peak times would allow for greater energy security and help each country accelerate its low carbon transition.

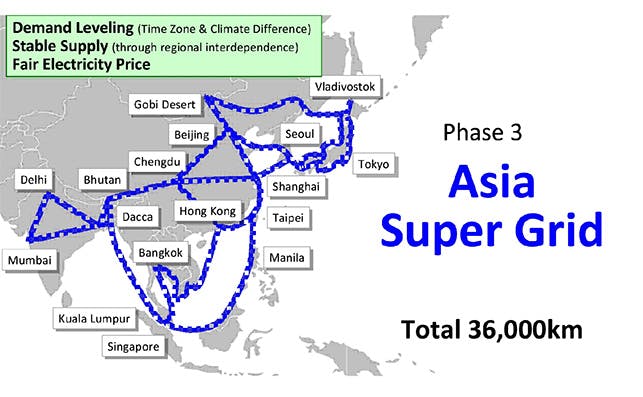

This is the vision behind the Asia Super Grid, brainchild of Masayoshi Son, chief executive officer of Japanese multinational Softbank. Seeking to develop a renewable energy pathway for Japan after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, Son proposed building an interconnected grid in Northeast Asia that would link resource-rich countries Mongolia and Russia, to high-energy consumers Japan, China and South Korea.

“It’s an idea to connect Japan to other countries to expand the utilisation of renewables. South Korea and Japan are totally isolated in terms of grid connection, but if we see the distance between them and their neighbours, it isn’t too far,” said Mika Ohbayashi, director of the Renewable Energy Institute in Japan, adding that far larger interconnection projects already exist in Europe.

“If we compare to 10 or 20 years ago, both renewables and the technology needed to connect these countries have become very cheap,” she said, pointing to how China and Europe are using high-voltage, direct current (HDVC) electric transmission cables to transmit electricity across long distances at a lower cost than before.

Debabrata Chattopadhyay, power system planning group lead at the World Bank predicts that cross border transmission of electricity from renewables could displace a lot of fossil fuel energy generation in South Asia.

“There’s a lot of excess renewable capacity in India. During low demand periods, the surplus power could go to places like Bangladesh or Sri Lanka which lack renewable energy potential. This could replace a lot of its gas generation and delay or avoid some of the coal plants they are planning to build,” he said.

Furthermore, it would solve intermittency issues associated with fluctuating supply of renewable sources. Ohbayashi believes that installing more renewable energy plants across Asia will lead to a more stable and reliable energy management system as “somewhere in the region, the wind is blowing and the sun is shining,” providing a constant supply to the grid.

“

Instead of relying on individual local generating sources, a transnational energy network would enable a more stable supply of clean energy which could be transmitted to whenever there is demand.

Christopher Len, senior research fellow, Energy Studies Institute, National University of Singapore

Studies by the Asean Centre for Energy (ACE) also found that cross-border interconnection will help certain regions replace fossil fuel-based electricity with imports of cheaper, cleaner electricity from power plants that are closer than the national grid.

“In many cases, countries prefer to have a cross-border connection to electrify a region far from the main grid. It might be costly for them to extend electricity to that province, so it is more economically viable to import electricity from nearby,” said Aloysius Damar Pranadi, a research analyst for the power sector at ACE.

According to Pranadi, the issue of electricity access undergirds the development of cross-border energy interconnection in Southeast Asia, which was first proposed in 1997 with the Asean Power Grid.

“One of the social benefits from cross-border grids is providing universal access to electricity, which will improve by having more interconnection between countries,” he said.

The state of interconnectivity in Southeast Asia

Currently, eight cross-border interconnections are in operation in Southeast Asia, most of which trade electricity generated from hydropower. In 2016, Malaysia’s Sarawak Energy Berhad (SEB) started exporting cheap hydropower-generated electricity to West Kalimantan via a transmission line from Bengkayang in Kalimantan to Mambong in Sarawak.

Although West Kalimantan could continue to develop coal-fired power plants locally, it opted to access electricity from cleaner hydropower in Malaysia, stated a paper by the Asian Development Bank. One benefit of deploying the cross-border grid was that it was faster to implement than a coal power plant, which can take seven to ten years to develop.

Currently, an interconnected grid linking Laos, Thailand and Malaysia is the only multilateral grid in Southeast Asia. Thailand, which sells the electricity it buys from Laos to Malaysia, has also recently expressed that it plans to become the region’s power trading hub by reviving the original Asean Power Grid idea.

Although plans to connect power plants in Southeast Asia have been discussed for decades, lack of government coordination, infrastructure funding, differences in electricity prices, and the protection of domestic industry have stalled the development of large scale, multinational energy trade.

However, Wattanapong Kurovat, director general of Thailand’s energy policy and planning office, recently said that the country “has the capacity and the infrastructure to become the regional hub” as the kingdom looks to achieve 35 per cent renewable energy production by 2037.

According to a 2017 report by the International Energy Agency, improved connectivity between countries could pave the way for large renewable projects in developing countries that otherwise would not have the demand to use them, such as hydropower in Laos or wind power in Vietnam.

However, Len said that for such a system to function effectively, robust market mechanisms and a strong degree of trust have to exist within states.

In Southeast Asia, challenges lie in their differing energy markets, which predominantly follow a single-buyer model with independent power producers (IPPs). In countries such as Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, Malaysia and Indonesia, national and state utility companies hold a monopoly over their respective jurisdictions, while Singapore and the Philippines have liberalised energy sectors with market-driven tarriffs.

Similarly, Japan only started opening its energy market in 2016. However, according to Ohbayashi, the Japanese government remains opposed to the idea of importing energy from abroad because they do not want to introduce cheaper electricity from outside players.

Despite the challenges, she believes that trading clean energy across borders is the best way forward for countries who share the common goal of reducing their carbon emissions and integrating renewables into their energy mix.

“Asian countries have long traded with one another, but cross-border electricity trading will require another level of trust between us. A new era of prosperity and stronger ties, driven by clean energy, will be brought on by clean energy interconnectivity.”