For generations, fisherfolk living near the calm and crystal clear waters of the Nabaoy River in Aklan, Central Philippines, depended on traditional methods for their daily catch. Rattan and bamboo fish traps, referred to locally as aeat and taun, and often handcrafted by local artisans out of readily-available natural materials were often used.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Women fishers, on the other hand, would scrape the shallow ends of the river with their traps, such that the current would lead the fish into the mouth of their wicker baskets. In another method known locally as panakeob, fish and eels are lured by ground pieces of coconut meat, then transferred into traps.

These traditional non-destructive fishing practices have for a long while protected the riverine system, rich in biodiversity, and located just downstream from parts of a protected national park. In recent years, however, holding on to this heritage has proved difficult for the local community of Nabaoy, as it puts them at a disadvantage, amid longer wet seasons and declining catches.

Some of the most affected have begun seeking opportunities elsewhere – as labourers and daily wage workers in the lowland towns – endangering the longevity of the sustainable fishing practices that have kept the Nabaoy River and watershed pristine all these decades, despite the large-scale development of Aklan province.

“It is a sad reality that the community here in Nabaoy, like other vulnerable frontline communities around the world, may contribute the least to our global carbon emissions, but are among the hardest hit by climate change-spurred natural disasters,” advocacy group Team Bintuwak co-founder and Aklan Trekkers Group member Ritchel Cahilig told Eco-Business.

“

The fishing practices of Nabaoynons are traditional practices. They are not invasive, they are not destructive to the environment. That is why I think the river and watershed remain pristine to this day.

Ritchel Cahilig, co-founder, Team Bintuwak

Nabaoy, at some 600 metres above sea level, and situated alongside four other highland barangays in the Malay municipality in Aklan, has become increasingly susceptible to perennial flash floods and landslides due to the river overflowing amid heavier rainfall and more frequent typhoons, according to the geohazard assessment of the Philippine Mines and Geosciences Bureau.

“It is environmental injustice. A lot of our communities living on the fringes are the most susceptible to climate change, not only due to the proximity of their homes to, but also due to their dependence on bodies of water like the Nabaoy River for their livelihood,” Cahilig said.

Cahilig – alongside Ronald Maliao, Richard Cahilig, and Beverly Jaspe – is a core member of Team Bintuwak, a group that wishes to document and preserve disappearing Indigenous knowledge systems and practices (IKSP) passed down through the generations of the communities along the Nabaoy River.

In panakeob, ground pieces of coconut meat are used to lure fish and eels so they can be transferred into the indigenous fish traps. Image: Team Bintuwak

The team hopes to enrich the public’s understanding of nature and its contribution to people, as well as potentially inform inclusive local policy that has both the welfare of the environment and the community in mind.

Through scientific studies, forums and dialogues organised to enable a two-way conversation between the local community and the government, as well as the production of a series of documentaries showcasing life among the Nabaoy fisherfolk, it also wants to keep proper records of the sustainable practices of the community.

In one of these documentary films, one Nabaoy local shares how the community has been impacted. “When there is heavy rainfall, we cannot catch fish using traditional practices as the water is too murky. We need to protect this river [from the effects of climate change], otherwise we will lose our livelihoods.”

In this interview, Cahilig tells Eco-Business why preserving these sustainable fishing practices is vital, and how adopting them in other parts of the country may restore life to other riverine ecosystems in the Philippines.

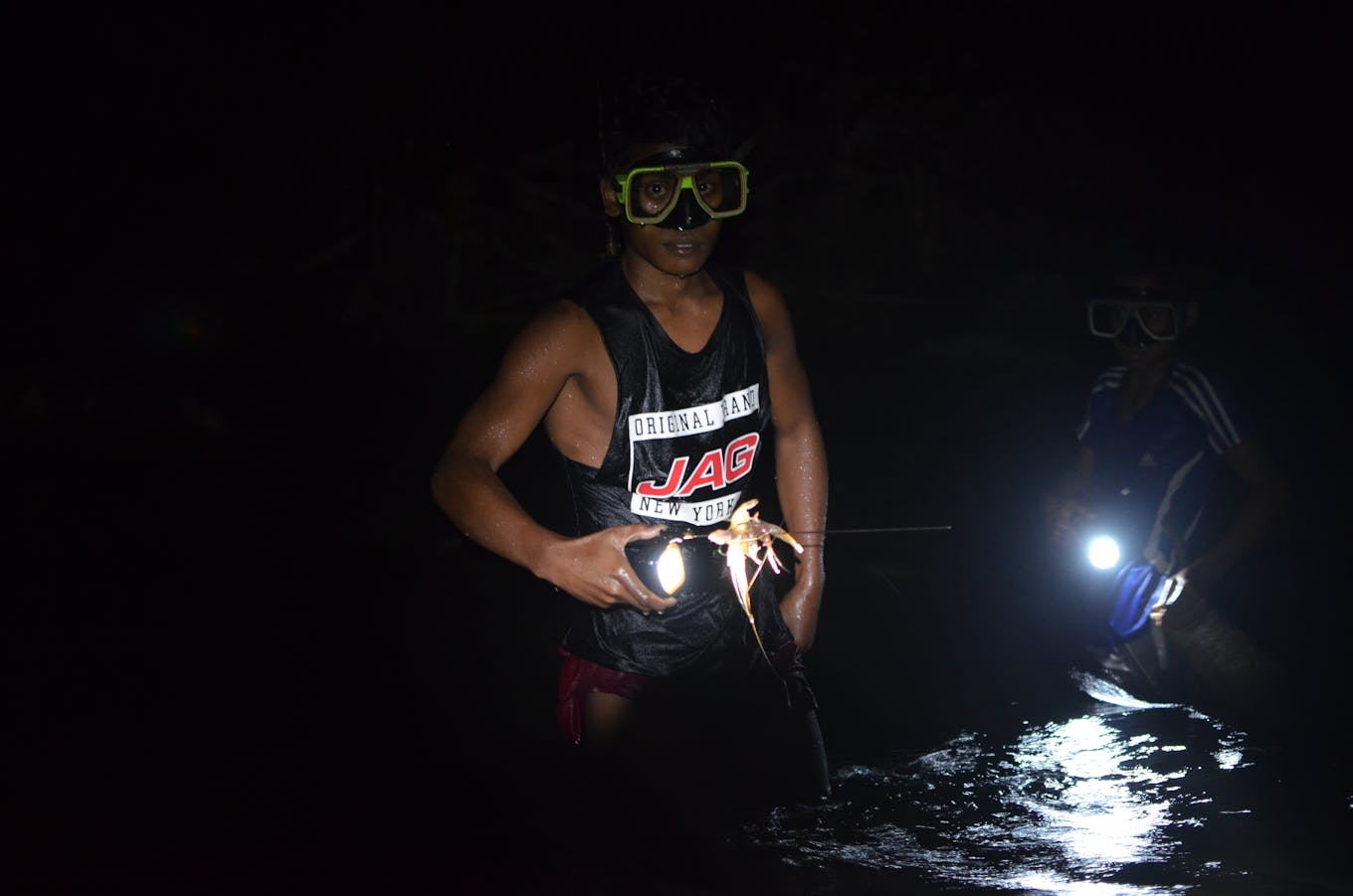

The species that inhabit the body of water include endemic freshwater prawns (known locally as patuyaw), crayfish, eels, crabs, and small fish, as well as banag snails which is an Aklan delicacy. Image: Team Bintuwak

Tell us about the community in Barangay Nabaoy. How far is the area from the nearest town?

Barangay Nabaoy is located in the town of Malay in the province of Aklan, Western Visayas in central Philippines. It is a 30-minute-drive away from the municipality of Caticlan, the jumping-off point to the popular tourist destination Boracay Island, and the route requires you to traverse both paved and dirt roads. Geographically, a large portion of the site is mountainous and forested.

Nabaoynons [people of Nabaoy] subsisting along the river are the immediate stewards of the Nabaoy River watershed which is the main source of potable water supply for the community of mainland Malay, Aklan and the island of Boracay. A pristine portion of the watershed is located inside the Northwest Panay Peninsula National Park (NPPNP). The park includes the last remaining swathes of primary lowland rainforest in the central Philippines.

What is the community’s main source of livelihood? What are the difficulties they face every day?

Most of the villagers engage in agriculture, such as upland farming and the production of copra (dried coconut kernels). Meanwhile, those who reside near the Nabaoy River rely on fishing for their livelihoods.

However, based on the findings of our study, there has been a severe decline in the community’s fish catch from the Nabaoy River since the 1960s. The species that inhabit the body of water include endemic freshwater prawns (known locally as patuyaw), crayfish, eels, crabs, and small fish, as well as banag snails which is an Aklan delicacy.

Nabaoy, at some 600 metres above sea level, and situated alongside four other highland barangays in the Malay municipality in Aklan, has become increasingly susceptible to perennial flash floods and landslides. Image: Team Bintuwak

We interviewed a total of 126 households residing along the Nabaoy River and some 31 per cent of the respondents reported fishing as their main source of livelihood. Of this, 77 per cent are fully reliant on fishing with no alternative or supplemental livelihood. The yield of fisherfolk along the river today is only 59 per cent relative to the catch in the 1960s.

Due to climate change, more frequent flash floods, landslides, and siltation along the Nabaoy River, the community’s source of livelihood and sustenance has increasingly come under threat, affecting the quality of life of Nabaoynons. These communities are incredibly susceptible to extreme weather phenomena because once the forest cover degrades in the higher elevation areas it becomes a catch basin for the rainwater, resulting in flooding.

How large is this community? How many Indigenous households rely on the Nabaoy River for their livelihood?

Nabaoy has a total estimated population of 1,300 composed of around 370 households. The Nabaoy River Watershed crosses the villages of Nabaoy, Napaan, Cubay Sur, and Motag.

Barangay Nabaoy is located in the town of Malay in the province of Aklan, Western Visayas in central Philippines. Image: Team Bintuwak

Tell us about the Kinaiya it Kailayahan project and the work that Team Bintuwak does. How did this initiative come to be? Who were your partners in making this endeavour a reality?

Kinaiya it Kailayahan is an Akeanon praise that basically means Indigenous knowledge systems and practices, or IKSP. Through this project, we hope to document the local community living upstream of the Nabaoy River Watershed and help share their sustainable practices.

This is a collaborative project between the Aklan Research Centre for Coastal Studies, which is based in the Aklan State University Washington campus, the Community Resilience and Environmental Education Development (CREED) Foundation, and the Aklan Trekkers group. Our collective is called Team Bintuwak and it is composed of environmental advocates and marine biology researchers, all responsible mountaineers with various experiences in outreach missions and who have shared passions for grassroots conservation and environmental education.

This project was incepted after the Oscar M Lopez Center for Climate Change, Adaptation and Disaster, Risk Management Foundation Inc. called for proposals to produce objective community-based research and climate change reporting that focus on all dimensions of climate change, as well as its impact on Philippine communities and vulnerable groups.

Our team submitted a pitch on the importance of IKSP in riverine conservation and integrating such knowledge in developing local adaptive mechanisms for climate change resiliency, We were awarded the seed grant and subsequently accepted into the Umalohokan Fellowship of the Balangay Media Project.

Nabaoy’s women fishers predominantly engage in panikop, or using fish traps to scrape the shallow ends of the river while letting the current lead fish into the mouth of the wicker basket. Image: Team Bintuwak

What inspired Team Bintuwak to document the Indigenous and sustainable fishing practices in Nabaoy? Are these communities still heavily reliant on these communities to this day?

Team Bintuwak aims to enhance the understanding and appreciation of the public towards the importance of IKSP in riverine conservation. We hope to integrate such knowledge and make the local community partners in developing local, adaptive mechanisms for climate change resiliency.

The main rationale of this project is to tap into the huge potential of the IKSP holders of Nabaoy River in Malay, Aklan to preserve traditional knowledge that may contribute in enhancing local, social, ecological, and climatic adaptation and resiliency.

Consequently, this will assure that our region’s freshwater riverine ecosystems will be highlighted as a centrepiece in local climate change discourse and promote the IKSP associated with these ecosystems, thereby paving the way for culturally-relevant climate change adaptation policies with the local community as our partners.

The fishing practices of Nabaoynons are traditional practices. They are not invasive, they are not destructive to the environment. That is why I think the river and watershed remain pristine to this day.

The non-invasive fishing practices of the people along the Nabaoy River have remained unchanged for generations, employing tools handcrafted by local artisans and the fisherfolk themselves out of local materials like bamboo, palm fronds, and coconut husks. Image: Team Bintuwak

What does your group hope to achieve by partnering with the community in Nabaoy?

In hopes of inspiring a new generation of environmental champions, we have helped found a youth group named Kinaiya it Kailayahan Advocates. We hope to sustain long-running advocacy-driven knowledge sessions as well as learning events to deepen the understanding and appreciation of the Nabaoynon and Aklanon youths on climate science and climate impacts, empowering them to speak up and enhancing their knowledge when it comes to the environmental challenges of Nabaoy River watershed.