The term “invasive alien species” refers to a species that human activities have enabled to move into a region outside its native habitat and that has established a self-sustaining population there, with negative impacts for local biodiversity and ecosystems.

The report, published in part earlier this week, pulls together more than 13,000 scientific studies, as well as Indigenous and traditional knowledge. (The summary for policymakers, or SPM, was released on 4 September. According to IPBES, the full report will be published later this year.)

It warns that, using conservative estimates, biological invasions cost the world US$423bn per year – a number that has risen fourfold since the 1970s. And under a “business-as-usual” scenario, the total number of alien species is projected to increase by more than a third by 2050.

The report also finds that climate change and land- and sea-use change are playing “increasingly important” roles in the establishment and spread of invasive species – and the former “will be a major cause” of the spread of invasives in the future.

For example, the cane toad, introduced to Australia in 1935 in an unsuccessful attempt to control the cane beetle, is projected to spread further across that country in response to a warming world.

Prof Helen Roy from the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, who was one of the co-chairs of the report, told a press briefing:

“We know that things aren’t remaining unchanged. We know that climate change is worsening. We know that land and sea change are worsening and so, therefore, we anticipate that the threat posed by invasive species will also worsen.”

Invasive species can also contribute to “worsening the impacts of climate change [across] the whole planet”, added Dr Aníbal Pauchard from the University of Concepción in Chile, another co-chair of the report.

The report also addresses tools and strategies for managing the spread of invasive species, from the local level to international governance. Curtailing the uptick of invasions is “achievable”, the report says, but will require significant investment and resources.

Ultimately, the report concludes that addressing such a global challenge will require global cooperation. Pauchard told the briefing:

“One of the most important messages of this assessment is that people and nature all around the world are threatened by invasive alien species. In all regions, all ecosystems, wherever you are in the world, you must be feeling the effects of invasive alien species.”

In this in-depth Q&A, Carbon Brief explains the report’s key takeaways.

What is the IPBES invasive alien species report?

The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is the world’s leading scientific authority for biodiversity. It is the biodiversity equivalent of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

IPBES was formed in 2012, 24 years after the IPCC was formed. Unlike the IPCC, though, IPBES is not a United Nations body. Some experts have suggested that the gap reflects – and may have contributed to – biodiversity loss receiving far less attention than climate change over the past few decades.

IPBES released its first major global assessment in 2019, with a headline finding that a million plant and animal species now face extinction because of humans.

“

One of the most important messages of this assessment is that people and nature all around the world are threatened by invasive alien species. In all regions, all ecosystems, wherever you are in the world, you must be feeling the effects of invasive alien species.

Dr Aníbal Pauchard, researcher, University of Concepción

The global assessment identified “invasive alien species” as one of the five key threats facing biodiversity, alongside land- and sea-use change, species exploitation, climate change and pollution.

Because of this, governments instructed IPBES to produce a report specifically on invasive alien species.

The resulting report was produced by 86 researchers from 49 countries. It took four-and-a-half years to complete, drawing on 13,000 scientific references and the perspectives of Indigenous peoples.

It is the most comprehensive global assessment of invasive alien species ever carried out.

On Saturday 2 September, the report’s summary for policymakers (SPM) was approved by the 142 governments that are members of IPBES during a plenary session in Bonn, Germany. The meeting also saw IPBES appoint a new chair in Dr David Obura, a biodiversity scientist and founding director of Coastal Oceans Research and Development in the Indian Ocean (CORDIO) East Africa, a non-profit research centre based in Kenya.

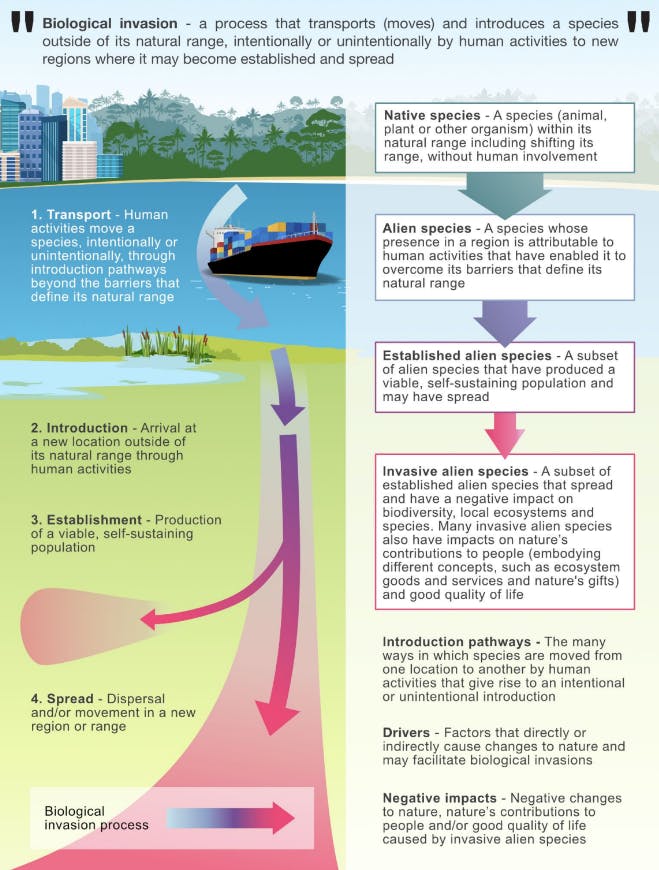

The report uses a number of technical terms, including “native species”, “alien species”, “established alien species” and “invasive alien species”. These terms are defined in the right-hand side of the figure below, taken from the report’s SPM.

According to the figure, a “native species” is an animal or plant within its natural range. This includes species that shift their range without human involvement.

An “alien species” is an animal or plant whose presence in a region is attributable to human activities that have enabled it to move out of its natural range. (These human activities could include those that directly transport species around, such as global trade and globalisation, or those that indirectly facilitate the movement of species, such as climate change.)

An “established alien species” is a subset of alien species that have produced a viable, self-sustaining population – and may have spread.

An “invasive alien species” is a subset of established alien species that have a negative impact on biodiversity, local ecosystems and people who rely on nature.

The left-hand side of the figure, meanwhile, explains the four stages of a “biological invasion”.

The term “biological invasion” is used to describe the process involving the intentional or unintentional transport or movement of a species outside its natural range by human activities and its introduction to new regions.

According to IPBES, the four stages of a biological invasion are:

- Transport. This occurs when human activities intentionally or unintentionally move a species outside of its natural range.

- Introduction. This is when a species arrives at a location outside of its natural range.

- Establishment. This is when an alien species produces a viable, self-sustaining population.

- Spread. This is when an alien species disperses, possibly spreading into further new areas.

A graphic explaining several technical terms used in the IPBES invasive alien species report. Credit: IPBES (2023) Figure SPM.1.

The report uses a “four-box” approach to stating the level of confidence in its findings.

This includes:

- Inconclusive for when both the quantity and quality of evidence and level of scientific agreement are low.

- Unresolved for when the evidence is high but the agreement is low.

- Established but incomplete for when the evidence is low but the agreement is high.

- Well established for when both the evidence and the agreement are high.

How many invasive alien species are there?

People and nature in every region of Earth are currently threatened by invasive alien species, the report says.

Humans have introduced more than 37,000 alien species across the globe, the report says. Scientists have documented negative impacts for 3,500 of these species, it adds.

Some 37 per cent of all known alien species have been recorded since 1970, the report says with established but incomplete certainty. And the number of new alien species is currently rising at “unprecedented and increasing rates” of 200 a year.

The proportion of alien species that are invasive varies among different animal and plant groups, ranging from 6 per cent of all alien plants to 22 per cent of all alien insects, it says.

Some 20 per cent of all the impacts of invasive alien species have been recorded on islands. (Islands are biodiversity hotspots where unique animals and plants have evolved to suit their specific surroundings, away from mainland threats such as predators and alien species.)

More negative impacts from invasive species have been recorded on land than in the sea, the report says. Temperate and boreal forests, woodlands and agricultural land have seen a particularly high number of negative impacts reported.

Around one-quarter of recorded negative impacts have occurred in the oceans and freshwater systems.

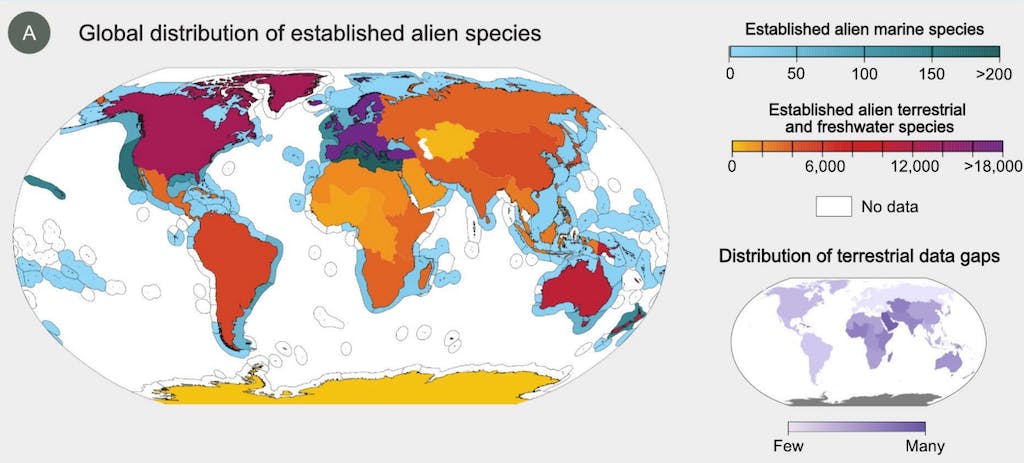

The map below, taken from the SPM, shows the global distribution of all known established alien species occurrences in the land and sea, with dark purple indicating higher numbers.

But it is also worth noting that regions with relatively few cases of alien species recorded also tend to be regions where the highest data gap currently exists (see inset purple map).

The global distribution of all known established alien species occurrences in the land and sea. Inset: The distribution of data gaps for land alien species. Credit: IPBES (2023) Figure SPM.4A.

The report says that “global exploration and colonialism, with the associated movement of people and goods” since 1500 and the industrial revolution have been “historically important” in the spread of alien species.

It adds that increases in global trade since 1950 “have resulted in unparalleled high and increasing numbers of alien species introductions”.

Even if humans stopped the introduction of new alien species tomorrow, the alien species that are already established are likely to continue expanding their geographic ranges, spreading into new countries and ever-more remote locations, such as Antarctica, the Arctic and the world’s great deserts, the report says with well established confidence.

It adds that there are often time lags between when an alien species arrives somewhere new and when it is detected by humans. Some invasive alien species “spread very rapidly while others take longer to spread and fully occupy their potential ranges”.

Under a “business-as-usual” scenario assuming past human drivers of invasive species continue at the same rate (see: How do invasive alien species spread to new regions?), the total number of alien species is projected to be 36 per cent higher in 2050 than it was in 2005, the report says with established but incomplete confidence.

But the impact of humans is projected to accelerate further in the future, meaning the number of alien species is expected to increase faster than under the “business-as-usual” scenario, the report says with established but incomplete certainty.

There is a lack of quantitative research into how invasive alien species might change under different future scenarios, which “impedes a comparison of trends for alternative futures”, the report says.

How do invasive alien species spread to new regions?

It is well established that many human activities – both intentional and unintentional – are facilitating “biological invasions” around the world, the report says.

Historically, many invasive species were introduced outside their natural range intentionally for their “perceived benefits to people” – such as for use in forestry, agriculture, horticulture and aquaculture – without consideration of their negative impacts, according to the SPM.

For example, Japanese knotweed was brought to the UK as an ornamental plant in 1850 to be grown by the “upper classes”. However, it was soon released into the wild, where it spread rapidly, and infestations of the hardy weed can now be found all over the UK. According to one estimate, 5 per cent of UK homes are afflicted with knotweed, knocking £20bn off their collective value.

More than 35 per cent of “alien freshwater fish” in the Mediterranean Sea have resulted from aquaculture, the report says. It adds that 150 years after the opening of the Suez Canal – which enabled the spread of previously separated species – new marine alien species, such as the lionfish and blue crab, are still being recorded in the Mediterranean Sea.

Species are also introduced to new ecosystems for “recreation”, for example, for use as pets, the report notes. Drug-cartel leader Pablo Escobar famously imported exotic animals, including hippos dubbed his “cocaine hippos“, to his estate in Colombia.

After Escobar’s death in 1993, the hippos escaped and established themselves in the Magdalena river, where they bred rapidly. The hippos are now a major tourist attraction, but Colombian officials are struggling to manage the animals, which number in the hundreds.

Invasive species are often introduced unintentionally. For example, seeds of the parthenium weed were transported to several countries in the grain sent with aid shipments, the report says.

The increase in the transport and introduction of invasive alien species worldwide is mainly influenced by economic drivers – especially the expansion of global trade and human travel – according to the report.

The report notes that over the last 50 years, the global population has more than doubled, consumption has tripled and international trade has grown tenfold. It is well established that patterns in the global spread of species mirror shipping and air traffic networks, as many invasive species travel as contaminants in transported soils, as stowaways in shipments or clinging onto ships’ hulls.

The report warns that “biosecurity measures at international borders have not kept pace with the growing volume, diversity and origins of global trade (including e-trade) and travel”, adding that the biosecurity capabilities of most countries could soon be overwhelmed.

The accelerated establishment and spread of invasive alien species is mainly due to changes in land and sea use, the report says.

Marine infrastructure may change the functioning of marine ecosystems, enabling the spread of invasive alien species, according to the report. For example, the numbers of invasive alien species were reported to be 1.5 to 2.5 times higher on pontoons and pilings than on natural rocky reefs, it notes.

Increasing fragmentation and habitat disturbance, including changed grazing patterns or fire regimes or soil disturbance, can make land-based ecosystems more vulnerable to the establishment and spread of invasive alien species, the report says.

The report warns that climate change is expected to “lead to major changes in land and sea use” and to drive more extreme weather events including droughts, floods and wildfires.

Meanwhile, in several regions worldwide, grazing by animals such as horses and buffalo helps spread invasive alien plants.

Climate change is also expected to “enhance the competitive ability” of some alien invasive species, by expanding the regions where it is suitable for them to live.

The report warns that climate change and continued land-use change “may lead to future increases in the establishment and spread of invasive alien species in disturbed habitats and in nearby natural habitats”.

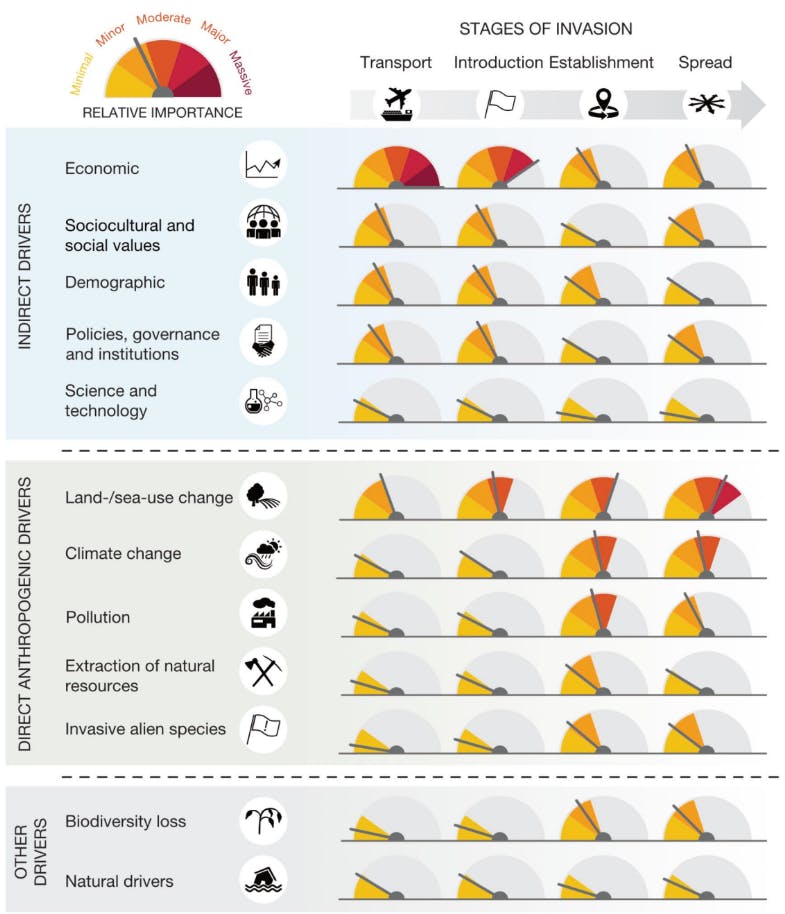

The figure below shows the relative importance of different drivers of facilitating biological invasions across different habitats during their transport, introduction, establishment and spread. Yellow indicates a low relative importance, while red indicates high importance. The top box shows indirect drivers, the middle box shows direct drivers and the bottom box shows other drivers.

Relative importance of different drivers in facilitating biological invasions across biomes during their transport, introduction, establishment and spread. Source: IPBES (2023) Figure SPM.5.

The report warns that different drivers can interact, amplifying biological invasions and “leading to outcomes that can be difficult to predict”.

Some of the highest rates of biological invasion occur when land-use changes interact with one or more additional drivers, the report says.

For example, land-use change, combined with climate change and nutrient pollution, have driven the introduction, establishment and spread of the water hyacinth across Africa. In Kenya’s Lake Naivasha, one-third of the water’s surface is now covered by the invasive weed, threatening local fish populations and rendering parts of the lake inaccessible to fisherfolk.

It is well established that invasive alien species can help other invasive species to spread, resulting in a positive feedback process known as “invasional meltdown”. For example, on Christmas Island, the arrival of the invasive yellow crazy ant drove down numbers of the native red crab population. This enabled an “explosion” in the population of the invasive giant African red snail, the report says.

The report finds that biodiversity loss can reduce the resilience of ecosystems to invasive alien species, enabling this feedback loop to begin.

Indirect drivers can also interact with one another. For example, sociocultural changes may lead to urbanisation, accelerating the pace of land- and sea-use change. All of these feedbacks could potentially lead to “numbers of invasive alien species never previously encountered”, the report warns.

How do invasive alien species affect people and nature?

Invasive alien species have a range of “dramatic and, in some cases, irreversible” impacts on both humans and native biodiversity.

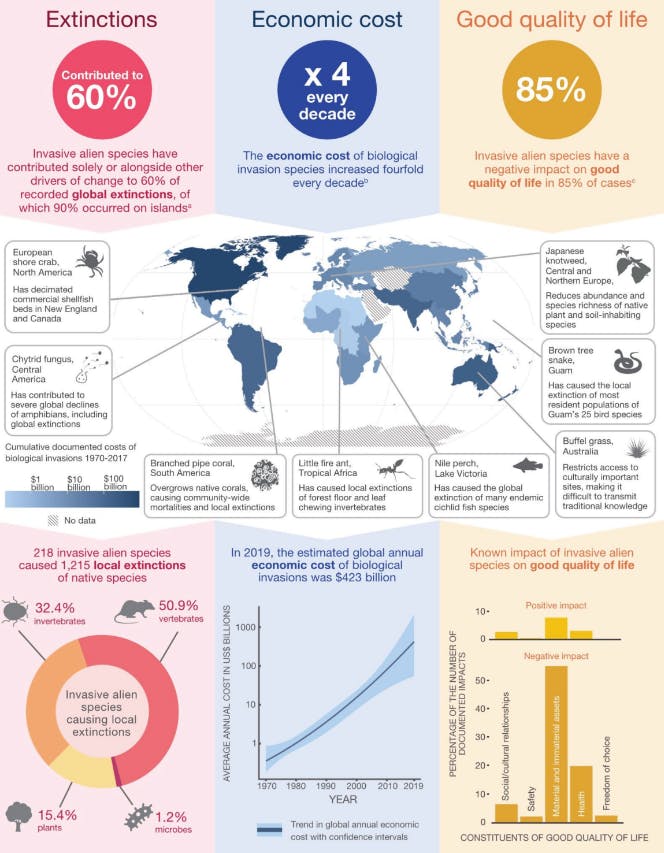

The global cost of biological invasions in 2019 was estimated at US$423bn, a number that the report says is “likely a gross underestimation”. Only 8 per cent of these costs were associated with management strategies; the remaining 92 per cent is directly attributable to damage to both people and quality of life.

These documented costs have risen fourfold every decade since 1970, and established but incomplete evidence indicates that they are “anticipated to continue rising”. A 2023 study found that the direct costs of invasive alien species to the UK in 2021 were more than £4bn, a 135 per cent increase over 2009 estimates. The report states that “a few people or sectors” often gain from biological invasions, but long-term costs are borne by the majority of others.

Around 85 per cent of the known impacts of invasive species on both nature and humans’ quality of life are harmful.

The most common impacts on biodiversity, according to the report, are changes to ecosystems, competition with native species, predation and herbivory. These “primarily” impact “the growth, survival and reproduction of individuals”, which can result in population declines and, eventually, extinctions.

According to established but incomplete evidence, invasive species have contributed to 60 per cent of known animal and plant extinctions globally. They are the sole known driver of 16 per cent of documented extinctions. For example, the invasive brown tree snake caused the global extinction of the Guam flycatcher, a small bird endemic to that island. The snake also caused “local extinction or serious population reduction” for most of Guam’s 25 resident bird species, the report adds.

In total, invasive species have driven more than 1,200 documented extinctions around the world. The majority of these – 90 per cent – have occurred on islands, which often contain uniquely susceptible species due to their isolation. Islands are also particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, “which can increase the rate of establishment and spread of many invasive alien species”, the report notes.

Invasive alien species have also driven 240 local extinctions in protected areas, emphasising that despite their protection, these sites are still vulnerable to the impacts of invasions.

The infographic below, taken from the report’s summary for policymakers, summarises key statistics from the report about the impacts of invasive species. The map in the centre shows the cumulative known costs of biological invasions since 1970, with darker colours indicating higher costs. Examples of invasions around the world are inset on the map.

Key statistics around the impacts of invasive alien species on nature, nature’s contributions to people and quality of life. The map shows the cumulative documented cost of biological invasions since 1970. Source: IPBES (2023) Figure SPM.3.

Another well established impact is “increased biotic homogenisation”, a decrease in uniqueness among biological communities. This can have negative effects on the “structure and functioning of ecosystems”, the report says.

Invasive species “overwhelmingly undermine” humans’ quality of life in myriad ways, the report finds in an established but incomplete conclusion.

Across all taxonomic groups and all regions, it is well established that a reduction in available food is “by far the most frequently reported impact” – comprising nearly two-thirds of documented impacts.

Non-native species can outcompete native ones for habitat or food supply, such as in the case of the Caribbean false mussel, which has “displaced native clams and oysters” that comprise important fisheries in some parts of India, according to the report. Invasive pests and pathogens can also directly impact agricultural products and yields.

In terrestrial ecosystems, invasive plant species are most frequently reported as having negative impacts, while in coastal areas, the most frequent impacts are associated with invasive invertebrate species.

Invasive mosquito species can function as infectious-disease vectors for pathogens, such as malaria, Zika and yellow fever. These vector-borne diseases disproportionately affect Indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, migrants and impoverished communities, the report says.

Invasive plants can also have direct health impacts, including by exacerbating allergies.

People who have the “greatest direct dependence on nature” are and will continue to be “disproportionately affected” by biological invasions.

According to the report, more than 2,300 invasive species are found across the lands of Indigenous peoples across the Earth. These can threaten their quality of life and cultural ties to the land, “often leading to general feelings of despair, sadness and stress”. For example, English ivy threatens cedar trees on Indigenous lands in British Columbia, Canada, where the trees have cultural significance in ceremony, medicine and weaving.

Invasive species “limit access to traditional lands, reduce mobility and require increased labour to manage” for Indigenous peoples. But, in some cases, invasive species are considered “a valued part of their nature”, the report adds.

There is also “some evidence” that the negative effects of invasive species disproportionately impact certain groups due to gender and age dynamics.

In Africa’s Lake Victoria, for example, fisheries – which are predominantly owned and operated by men – have significantly declined due to the spread of the invasive water hyacinth. In another example, women and children in east Africa are typically tasked with reducing the spread of the invasive prickly pear, which “requires repeated weeding by hand” and is a time-intensive activity for these groups.

Some invasive species also provide benefits to humans, such as food and fibre, the report says. For example, pigs introduced to the Hawaiian islands are “hunted for subsistence, ceremony and recreation”. But it adds that “those benefits do not mitigate or undo their negative impacts on nature, nature’s contributions to people and good quality of life across all regions and taxa globally”.

How can biological invasions be managed and what are potential challenges?

The report also addresses how to tackle and manage biological invasions.

The number of invasive alien species is on the rise, but containing the uptick of invasions and reducing their spread and impact is “achievable” through both short- and long-term management, the report states.

Broadly, the report identifies three well-established decision-making frameworks to manage biological invasions.

The first approach focuses on “introduction pathways” – the geographical routes and human activities that lead to the introduction and spread of invasive species.

This “pathways management” approach involves border-risk analysis, surveillance and biosecurity response measures such as inspections, quarantines and confinement.

Pathways management is “by far the most effective option” for managing biological invasions in marine and connected water systems, according to the report. Stronger international and regional cooperation are essential elements to make this approach work.

The report cites ballast-water management as a successful example.

Invasive alien species can be “stowaways” in ballast water, the fresh or sea water in ships’ cargo holds meant to keep vessels stable when navigating empty or on rough seas.

Ballast water discharges have introduced invasive species to coastal and inland water ecosystems, such as the zebra mussel in the Great Lakes of North America.

Zebra mussel populations and climate-change-induced warming are implicated in the death of waterfowl in the Great Lakes. After Canada and the US introduced ballast water management regulations following a landmark international legislation in 2004, there was an 85 per cent decline in the number of newly established alien species, according to the report.

Species-based management at a local or landscape level is another well-established option at each stage of the biological invasion process, per the report.

It includes surveillance for individual species, early detection and rapid response, eradication, containment and widespread control.

Finally, site-based management focusing on particular ecosystems can protect and help restore native species and regions.

Site-based and species-based interventions implemented together have successfully dealt with invasions on land and in closed-water ecosystems, especially in isolated areas such as small islands and lakes, the assessment says.

Together, they can “also enhance ecosystem functioning under ongoing climate and land-use change”, the report states. However, “ecosystem restoration has so far proved to be largely ineffective” in marine and connected waterbodies, it observes.

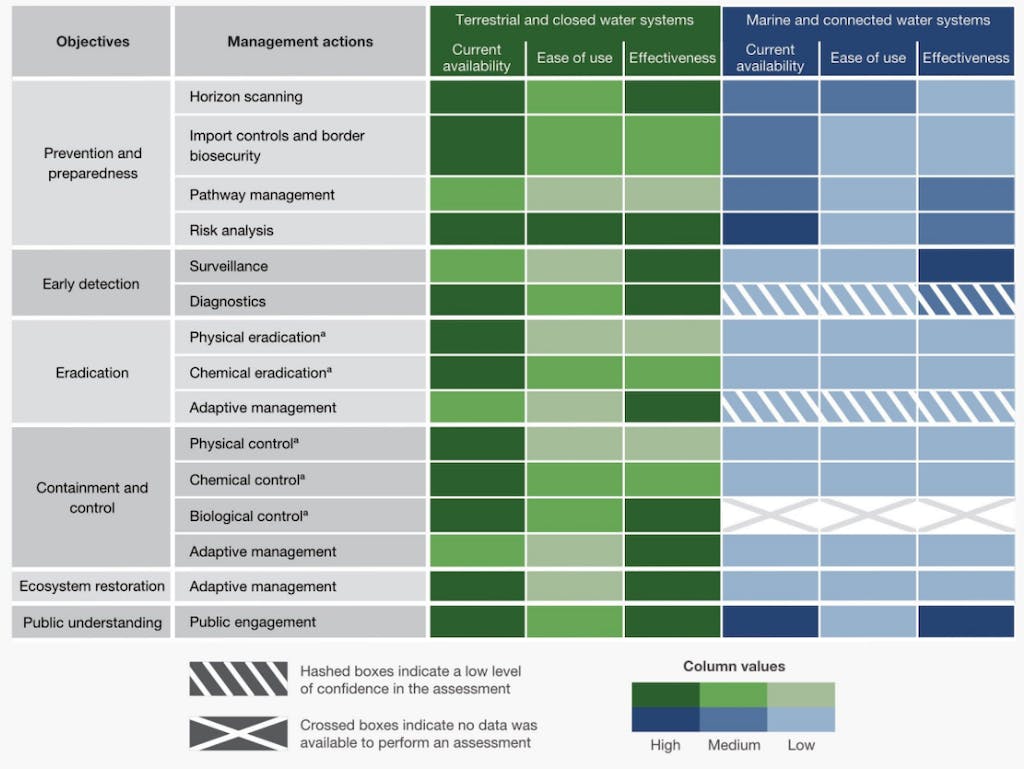

The table below lists the current availability, ease of use and effectiveness of different actions to manage biological invasions, with colour intensity denoting higher and lower values, hashed boxes indicating a low level of confidence and crossed boxes indicating no data was available for the assessment.

Objectives and actions for managing biological invasions. Source: IPBES (2023) Table SPM.1.

Of all the options for managing invasion threats, preventing introductions in the first place and preparedness are the most “crucial” and “cost-effective”, according to the assessment.

Prevention is vital on islands and ecosystems where eradicating species is particularly challenging.

Prevention can be achieved through pathway management, using measures such as strictly enforced pre-border quarantines and import controls, which have well-established success at slowing the rate of species arrival and establishment, it says.

Preparedness measures emphasise early detection and are critical to keep invasive species populations from establishing themselves. Horizon scanning and risk analysis are tools that aid both preparedness and prevention, by prioritising emerging invasive species threats.

However, effective prevention needs sustained funding, technical and scientific cooperation, technology transfer and monitoring. It also needs strong and relevant biosecurity laws and enforcement, along with infrastructure such as inspection and quarantine facilities. Such capacity building “is sometimes lacking, especially in some developing countries”, the report says.

At the same time, there is established but incomplete evidence that general surveillance strategies – from citizen science to remote sensing – can help preparedness efforts, according to the report.

For instance, the PlantwisePlus programme helps smallholder farmers in Africa, Asia and Latin America identify specific pests and damaged crops, helping with early detection of invasive outbreaks.

Where prevention and preparedness fail, eradication can sometimes work.

According to the SPM, eradication has worked to curb the spread of invasive alien species when their populations are small and spread slowly on isolated ecosystems such as islands. Over the last century, there have been 1,550 recorded eradications on 998 islands, with a success rate of 88 per cent, such as eliminating black rats and rabbits from French Polynesia.

However, invasive plant species and large-scale eradications are complex and often unfeasible. Additionally, there is no known marine example of an entirely successful eradication programme, the report states.

Finally, when eradication is not possible, invasive species can be controlled and contained, particularly on land and in closed water systems.

While physical and chemical control options can be effective on a local – and sometimes larger – scale, it is well established that these options are constrained by labour costs and generally only provide short-term suppression. Chemical options can also have unintended targets.

In contrast, it is well established that biological control to combat invasive alien plants and invertebrates has been successful in over 60 per cent of all documented cases, “while also leading to benefits to biodiversity and ecosystem resilience”. Measures to avoid unintentional impacts on humans and other species have been defined in the International Plant Protection Convention and widely applied.

New and emerging technologies, such as bioinformatics and environmental DNA (eDNA) can support the management of biological invasions, the report states. eDNA-based approaches, in particular, have been used to detect invasive aquatic species, such as rusty crayfish.

For any management programmes to succeed, decision-makers must enlist the support and engagement of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, it adds, with stakeholder engagement and collaboration shown to improve outcomes.

Engagement matters for social acceptability when there are conflicting perceptions around eradication, and management can also gain from sharing across knowledge systems, the report states. Additionally, recognising Indigenous peoples’ rights, knowledge and customary governance systems “also helps to improve long-term management”.

How can enhanced governance and international collaboration manage invasions?

The last chapter of the report outlines a set of policy instruments, governance strategies and international efforts to prevent and control biological invasions.

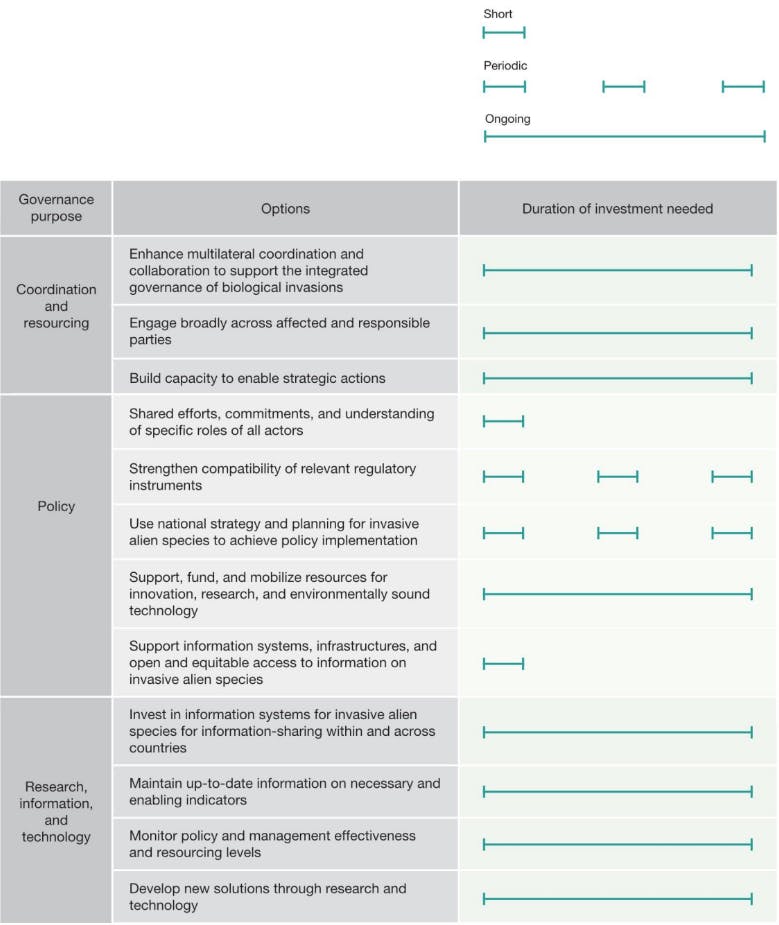

The report notes that national strategies and action plans are instruments to “successfully manage” invasive alien species.

It calls on countries to implement international agreements such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework within their national policies. Target 6 of that framework strives to reduce the rates of introduction and establishment of “known or potential” invasive species by at least 50 per cent by 2030.

Around 80 per cent of countries have targets to manage biological invasions within their national biodiversity strategies and action plans.

However, the report says there is “a considerable gap” between policies targeting invasive alien species and implementation at national levels. More than 80 per cent of countries do not have national legislation or regulations on invasive alien species, which puts both them and nearby countries at risk of biological invasions.

The document also urges strengthening national regulations for online trade, which is “key to reducing the transport and introduction of invasive alien species”.

Some agribusiness companies have developed voluntary codes of conduct to reduce the transport or introduction of invasive alien species through trade, complementing government regulations, the report says.

Codes of conduct encourage companies to display information for consumers, such as the potential invasiveness of certain species or measures to prevent escape. The European code of conduct for botanic gardens on invasive alien species, for example, lays out guidelines for personnel working in these places to prevent the impacts of invasive alien species.

The report finds that 45 per cent of countries do not invest in biological invasion management.

It also points out a need for more awareness of coordinated responses.

Transportation of invasive alien species may be “poorly managed” and “constitute a biosecurity risk” due to different capacities and resources among regions and unclear responsibilities for stakeholders, the report says.

The world has committed to preventing biological invasions through many international agreements and bodies, including the Convention on Biological Diversity, the World Trade Organization, the International Maritime Organization and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

However, these are not aligned, the report says. As a result, collaboration across these mechanisms is crucial to reach “a coherent approach” to solve the problem. Such a collaboration should consider different stakeholders, including Indigenous peoples and local communities, it adds.

The report encourages the mobilisation of resources, research and technology, as well as information systems and data sharing.

It points out that governments and institutions should provide “sustained investment and resources”, support developing countries and address the gaps in policy instruments.

To incentivise investment in preventing and controlling invasive alien species, the report suggests implementing both regulatory and market-based instruments, such as tax credits or subsidies, which could be especially effective when responsibilities for biological invasions are shared.

There are also non-market mechanisms and regulations, including information-sharing, product labelling and direct regulations.

Economic penalties and tariffs can help enforce those regulations, says the report.

Governments can carry out cost-benefit and “willingness to pay” analysis and consultations with stakeholders to justify using public funds for this aim.

The chart below shows options for governance of biological invasions at national, regional and global levels. The green bars on the right-hand side indicate the duration of investment needed.

Governance options for addressing the threat of biological invasions and the duration of investment needed to implement these actions. Source: IPBES (2023) Table SPM.2.

According to the report, public understanding of the risks of invasive alien species “is particularly important”. Therefore, it recommends boosting public awareness campaigns, education across all age groups and citizen science programmes. Ultimately, the report concludes that Indigenous peoples and local communities hold “invaluable knowledge” to deal with biological invasions. In fact, the document itself was built based on scientific, Indigenous and local knowledge, said Dr Anne Larigauderie, executive secretary of IPBES, during a press briefing.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.