This core component of the Paris Agreement involves an exhaustive appraisal of how far the world has come in tackling climate change and how far it still has to go.

Over the past two years, governments, scientists and civil society groups have submitted thousands of documents into this process and spent hundreds of hours debating their contents.

The main technical conclusions emerging from the stocktake are not new. Nations are not cutting emissions fast enough, they are not sufficiently prepared for climate hazards and developed countries are not providing enough support to developing countries,

But the stocktake is more than just a review of progress. It is a key part of the Paris Agreement’s “ratchet mechanism”, which encourages countries to scale up their climate ambitions over time so as to avoid dangerous warming.

Governments have submitted proposals for how the main, political outcome of the stocktake could accelerate climate action. Ideas include phasing out fossil fuels, tripling renewable energy capacity and raising climate finance to the trillions that developing countries need.

At COP28, countries will negotiate which elements make it into the final outcome, which will help determine the pace of change in the coming years.

However, one expert tells Carbon Brief that, with so much on the table, the global stocktake risks becoming a “dumping ground” for “politically thorny discussions”, which may hamper its ability to drive meaningful change.

What is the global stocktake?

The global stocktake (GST) is a five-yearly temperature check that is a vital part of the Paris Agreement, housed under Article 14.

Nations that signed on to the agreement in 2015 also agreed to monitor, assess and periodically review collective progress towards meeting the Paris long-term temperature goal and to take stock of their climate actions.

The GST is meant to help countries collectively assess where they are, where they want to go and how to get there in terms of climate action and to identify gaps to course correct.

It is meant to be an assessment of mitigation and adaptation actions so far, as well as climate finance provided and technology transferred from developed to developing countries, “in the light of equity and the best available science”, per the Paris Agreement.

“

We’re not going to get to where we need to without engaging with a wider landscape of action and actors, and engaging with the idea of the stocktake and the Paris Agreement as trigger[s] and catalys[ts for] domestic policy shifts towards the transformations that we need.

Dr Lavanya Rajamani, professor of international environmental law, University of Oxford

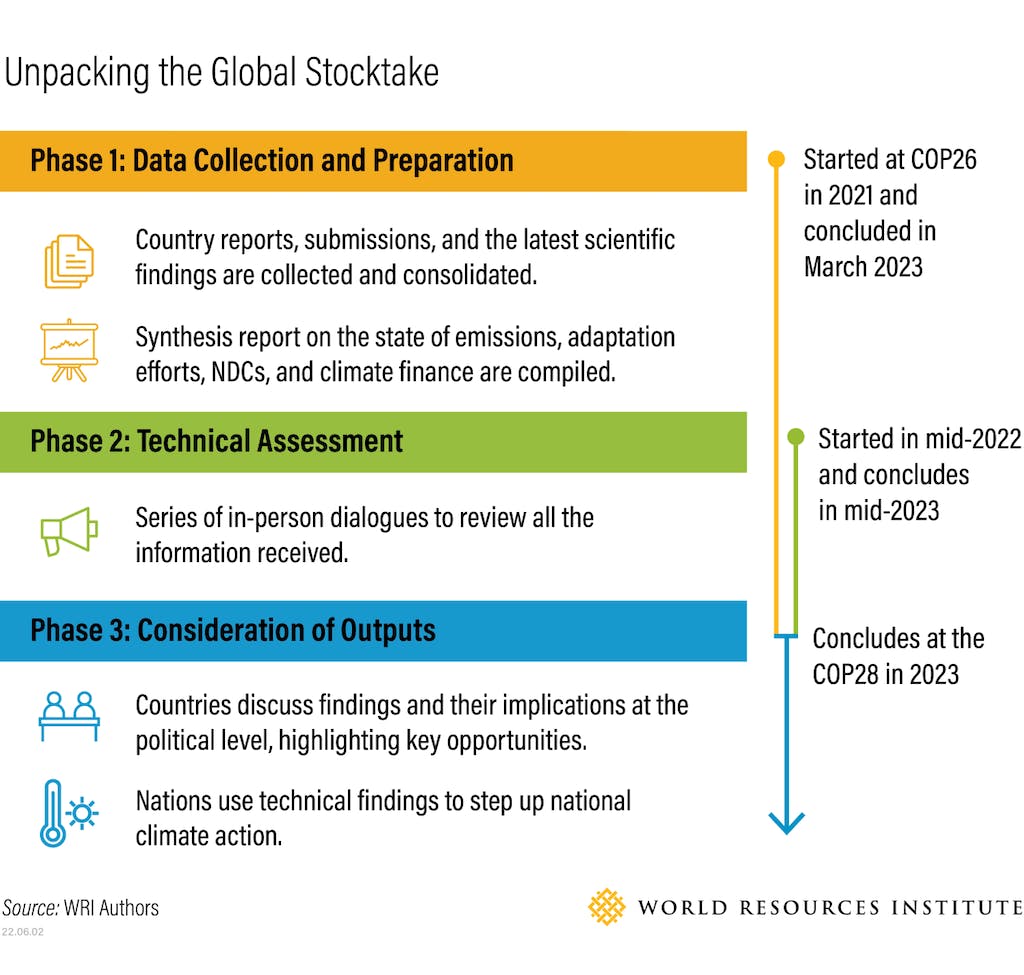

The GST is split into three phases: an information collection phase to gather inputs from all parties and non-parties, a technical assessment phase of these inputs and other evidence, and a “consideration of outputs” phase, for countries to decide what to collectively take away from the process.

The final, political phase is scheduled to conclude at COP28, to inform the next round of submissions of countries’ climate pledges in 2024-2025 and to “enhanc[e] international cooperation for international climate action”.

What is the scope of the stocktake?

The information feeding into the GST comprised more than 170,000 pages of documents from governments, business and civil society groups, supported by over 252 hours of meetings and discussions.

These submissions were categorised into three main areas of climate action, which were decided back in 2018 at COP24 in Katowice, Poland.

Nations agreed to evaluate progress on mitigation – cutting emissions – as well as adaptation to climate hazards and “means of implementation and support”.

The latter point refers to how much finance has been raised to help developing countries take climate action. It also covers nations sharing low-carbon technologies and increasing their capacities to deal with the challenges ahead.

Parties specified numerous “sources of input”, including greenhouse gas inventories, assessments of national climate plans and analysis of adaptation projects.

They also agreed that the stocktake “may take into account, as appropriate” two more major topics.

These were the unavoidable loss and damage resulting from climate change and “response measures”, which includes the social and economic consequences of climate action, for example on people working in the fossil-fuel industry.

In the final synthesis report that emerged from the technical phase of the stocktake, which will inform political decisions taken at COP28, loss and damage was included as part of the section on adaptation. Response measures were filed under mitigation.

However, in the draft GST text that has been prepared ahead of COP28, these issues are separated out under their own subheads. Civil society groups have emphasised the importance of ensuring loss and damage, in particular, is prominent in proceedings.

How has the stocktake progressed so far?

The GST began after COP26 in 2021, with a period of data collection that continued until March 2023. Prior to this, parties had negotiated the rules of the stocktake process and what kind of “inputs” would feed into it.

During this period, country reports, scientific studies and other documents were submitted into the stocktake process for consideration.

The second phase – the technical assessment – began in June 2022. This consisted of three “dialogues” that took place at the UN intersessional talks in Bonn in 2022 and 2023, and at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh.

These sessions provided time for evidence to be discussed by country representatives, civil society groups and climate experts.

The dialogues proceeded relatively smoothly within the UN talks but, as Carbon Brief has reported, familiar issues emerged within them.

Examples include disputes between developed and developing countries over historical responsibility for climate change and civil society groups highlighting the role of fossil-fuel lobbyists in the discussions.

Timeline of the global stocktake process: Source: World Resources Institute.

The outcomes of each technical dialogue were recorded in summary reports released a few months after the close of each session.

These were followed by a 46-page synthesis report prepared by the stocktake’s co-facilitators, with the assistance of the UN Climate Change secretariat. This serves as a “comprehensive overview” of all the inputs and discussions.

The evidence laid out in this report will serve as the basis for the political part of the GST at COP28.

Nations have already submitted documents to the UN outlining how they interpret the synthesis report’s findings and the stocktake-related outcomes they would like to see emerge from the COP28 summit.

How could the global stocktake accelerate climate action?

The GST synthesis report concludes that there is a “rapidly narrowing window to raise ambition and implement existing commitments in order to limit warming to 1.5°C”.

Achieving the 1.5°C target, or even the “well below 2°C” goal, requires nations to fill the extensive “implementation gaps” between their climate strategies and real-world action.

It would also require them to come forward with new strategies that are Paris Agreement-aligned. According to the synthesis report, existing pledges would result in warming of 2.4-2.6C, with the possibility of cutting this to 1.7-2.1C if long-term net-zero targets are fully implemented.

As part of the Paris Agreement’s “ratchet mechanism”, the stocktake is explicitly intended to encourage such raising of ambition. There are several ways in which governments and civil society groups are proposing it could achieve this.

Much of the focus is on signalling to countries what they should submit in their new, enhanced climate plans, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

Nations are obliged to submit NDCs every five years and the next round is due in 2025. The synthesis report notes that “more ambitious mitigation targets in NDCs are needed to reduce emissions more rapidly”.

Greater ambition could involve new targets for both 2030 and 2035, and NDCs that cover emissions from entire national economies, not just parts of them.

It could also involve NDCs based on absolute emissions reductions rather than cuts in emissions intensity. (Many nations have targets based on reducing emissions per unit of GDP, even as their overall emissions increase.)

Article 4.4 of the Paris text says that developed countries should “tak[e] the lead” with “economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets”, whereas developing countries were “encouraged” to move towards “economy-wide emission reduction or limitation targets”.

As it stands, many developing countries with high emissions, including China, India and Saudi Arabia, have less comprehensive NDCs, as Tom Evans, a policy advisor on climate diplomacy at E3G, tells Carbon Brief:

“There [was] this agreement that developed countries would set economy-wide targets from the get go, and the developing countries would move towards setting them over time… Many of the developed countries – the EU and the US – [say] ‘over time’ is now.”

At COP26, nations were “requested” to come forward with more ambitious plans in 2022, but this was largely ignored. The 2025 deadline for new NDCs, on the other hand, is part of the original Paris Agreement and is therefore widely accepted.

In their suggestions for the GST outcome, some have made a point of emphasising that new NDCs should be submitted as early as possible – either “well ahead of” or up to a year before COP30, at the end of 2025.

Perhaps the most high-profile elements being considered for inclusion in the final stocktake outcome are sector-specific proposals, including targets for phasing out fossil fuels, tripling renewable energy capacity and doubling energy efficiency around the world. (For more on these ideas, and others, see: What are countries and blocs expecting from the stocktake?)

Another priority for some is ensuring that, beyond simply committing to global goals, countries use their new NDCs to explain how exactly they would contribute to such targets.

Evans tells Carbon Brief that while there is a lot of focus on “flashy” topics such as fossil fuel phaseout, NDCs remain the main mechanism for making the Paris Agreement work. “The NDCs are what you can actually hold everyone accountable to. It’s the agreed terrain,” he says.

Alongside measures to cut emissions, developing nations in particular would like to see the GST usher in greater ambition around climate adaptation.

The synthesis report concludes that progress on both adaptation and loss and damage “must undergo a step change in fulfilling the ambition set out in the Paris Agreement”.

Negotiations over a “global goal on adaptation” (GGA) will still be on-going at COP28. As a result, this component in the international effort to make countries more resilient to climate change will not feed into the stocktake.

However, Sandeep Chamling Rai, a global advisor on adaptation policy at WWF, tells Carbon Brief that the stocktake could still work to inform and reinforce the GGA:

“For this first round of the GST, parties might create a concrete link with the GGA and might have more concrete links established for the second global stocktake cycle.”

A key element of adaptation and mitigation efforts for many developing countries will be assurances that adequate climate finance is provided after the first stocktake.

Groups such as the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs) have made it clear that, from their perspective, any scaling up of mitigation ambition needs to go hand-in-hand with scaling up climate finance.

Avantika Goswami, a climate policy researcher at the Centre for Science and Environment in India, tells Carbon Brief:

“Without dedicated efforts to ramp up finance, you’re not going to achieve the triple [renewable] energy target, so that’s definitely something that needs to be reckoned with in the global stocktake outcome.”

The synthesis report concludes that “accelerated action is required to scale up climate finance from a wide variety of sources, instruments and channels, noting the significant role of public funds”.

More broadly, the report also says it is “essential to unlock and redeploy trillions of dollars to meet global investment needs” and make global financial flows consistent with Paris Agreement goals.

Countries must finalise a “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) for developing country climate finance in 2024.

Developing countries want to see a goal that is more ambitious and based on an assessment of their needs – rather than picked arbitrarily, as with the previous “US$100bn by 2020” target. Many have stated they want to see the analysis from the stocktake inform this new goal.

Alongside finance, developing countries have also pushed for the GST outcome to include language that encourages developed countries to share their climate technologies and provide more support for capacity building in developing countries.

What are countries and blocs expecting from the stocktake?

From “keeping 1.5°C alive” and fossil fuel phase-down language, to addressing unkept climate finance promises, countries’ expectations from the GST are varied.

Submissions made this year against the backdrop of increasing climate impacts reveal growing divergence between developed and developing countries.

Broader conversations suggest that the GST is being seen both as a defining moment for climate ambition for the coming decade and as a moment of accountability for decades of inaction.

Forward versus backward

One of the chief differences in expectation is whether the GST looks back at the lack of climate progress from the developed world to date – and if so, how far back does it look.

Alternatively, it could look more to the future and what should be done now, at a time when emerging economies contribute significantly to rising emissions and could arguably be expected to pledge more.

Developing countries that are part of the G77+China negotiating bloc demanded a full assessment of how rich countries have delivered – or failed to deliver – on their pre-2020 and post-2020 climate commitments.

The bloc called on the stocktake, in its political outputs, to highlight historical gaps in mitigation actions “since the start of the multilateral climate regime”. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was agreed in 1992.

The G77+China also asked that the GST cover results of work under the Kyoto Protocol, the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, while also suggesting that its outputs be “both backward and forward-looking”.

In contrast, developed countries including the UK, US, Japan and Australia stress the need for “forward-looking” GST outcomes, which encourage “major emitters” [a term seen by many as a loaded reference to India and China that obscures equity and historical responsibility for emissions] to “aggressively” increase the ambition of their 2030 and 2035 climate pledges.

Other developing country blocs, such as AILAC, have stated that the insistence on pre-2020 discussions “has only served to delay current deliberations” and that the “historical emissions gap is narrowing between developed countries and developing countries that have substantially increased their emissions.” The group called on “all Parties to be actively involved in climate action” but that “developed nations must exhibit stronger global leadership”.

According to analysis by the Centre for Science and Environment, BASIC, LMDC and African countries also raised the issue of inequities in IPCC models and their implications for decarbonisation, going forward.

Mitigation

The idea of “keeping 1.5°C alive” has historically been a rallying cry from Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries.

In their submissions, most developed countries, including the UK and Japan, called for a GST outcome that recommends policies that “keep 1.5 alive”, for global emissions to peak in 2025 and for all 2030 targets of “major emitters” to be 1.5°C aligned.

The US called for “phasing down unabated fossil fuel generation steadily and rapidly”, including “immediately ceasing to permit new unabated coal power generation”, as well as “increasing global carbon management capacity to capture 1.5bn tons of CO2 (GtCO2) annually by 2035.”

Russia, meanwhile, dubbed it “unacceptable” to analyse progress towards limiting the temperature rise to 1.5°C instead of 2°C, while suggesting gas should be considered “a transitional fuel”.

In turn, LMDCs submitted that the GST should “urge developed countries to achieve net-zero significantly ahead of the global timeframe”.

Meanwhile, Zambia on behalf of the African Group of Nations urged for “a political signal from COP28” that “affirms differentiated pathways for countries in the pursuit of net-zero and fossil fuel phasedown”.

It also suggested “no further exploration of fossil fuels in developed countries is targeted well ahead of 2030”, affording developing countries breathing space to close their energy access gap in the short-term.

In a joint US-China statement issued on 14 November, both countries stated that they were working together and with other countries to reach a consensus on a GST decision that could be adopted at COP28.

Elements put forward in the statement – such as “send[ing] signals with respect to the energy transition (renewable energy, coal/oil/gas)” – were significantly different from their individual positions on fossil fuels and on trade, indicating ongoing divergence.

Finance

Another key expectation from the GST is an assessment of climate finance failures so far, and how a new climate finance target can be informed by them.

“Trust has been eroded by inadequate delivery on the commitments made by developed Parties, including the failure to deliver on the US$100bn target for the mobilisation of climate finance, and also by the failure of leadership by developed countries which led to a woefully inadequate mitigation outcome in 2020, putting more pressure on developing countries with less resources,” said South Africa in its submission.

While developed countries, such as Australia, acknowledge the failure to deliver on the US$100bn target, they state that the stocktake should “celebrate and welcome the confidence of Parties that the goal is expected to be met” imminently and ask that “this should be more than a statement of disappointment, but a constructive reflection”.

Both Australia and the US called to increase the scope of countries providing climate finance, along with an assessment on whether finance furnished by rich countries so far has been effective, to increase donor confidence.

“The scope of countries that are capable of such support has evolved considerably since 2015, and the stocktake should reflect their responsibility in the decade of the 2020s and beyond,” said the US, in its submission to the GST.

Developing countries, including the Climate Vulnerable Forum, called for an assessment of pre-2020 climate finance, reform of multilateral development banks and not increasing the debt burden on vulnerable countries.

Adaptation and loss and damage

In their submissions, countries and blocs were generally in agreement that the framework for the Global Goal on Adaptation be finalised, and its targets inform and evolve with the GST.

On behalf of the African Group of Nations, Zambia called for the GST’s preamble to note “the lack of parity and balance in support between mitigation and adaptation” and to “affirm the understanding that adaptation and loss and damage are a global responsibility because they were caused by global emissions”.

The Least Developed Countries bloc called for a separate section on loss and damage, distinct from adaptation in the GST, while some developed countries sought to retain the existing structure.

While most developed countries echoed the need to operationalise the loss and damage fund that they agreed to at COP27, many referred to a “mosaic” of different sources and emphasised private finance mobilisation, with the US pointing to insurance solutions for loss and damage.

Trade, response measures and just transition

Trade policies, response measures and international cooperation also feature heavily in stocktake submissions, reflecting an external atmosphere pockmarked by geopolitical conflict.

In its September submission, China stated it wants the preamble to “acknowledge that the first global stocktake is taking place in rising unilateralism, protectionism, and anti-globalism, and enabling environment for climate actions is undergoing critical challenges, including inadequate means of implementation support, sanctions on low-carbon products and industries, restrictions on technology investment and cooperation, green barriers, discriminatory legislation [and] plurilateral constraints”.

G77+China, along with the LMDCs, expect the GST to “identify challenges to global cooperation” and prioritise multilateral measures over unilateral ones, such as trade barriers.

Latin American countries, in their submission, hoped for a broadening of the stocktake’s assessment of the socio-economic impact of response measures, given “unexpected consequences from initiatives such as deforestation control measures and low-carbon agricultural systems”.

The US meanwhile, highlighted its own domestic just transition policies, saying that “lack of implementation of response measures, especially by major emitters…building new unabated fossil fuel infrastructure not only contributes to global GHG emissions, but also risks stranded assets and job losses”.

Russia stated that the GST should “specifically consider the socio-economic risks and negative consequences of an accelerated phase-out of fossil fuels, including rising electricity prices, unemployment and capital expenditures for re-equipment of facilities.”

What do experts and observers expect from the global stocktake and what it means for climate action?

COP watchers, commentators and participants have markedly different views on what the outcomes of the GST will be and what they could achieve, much like the parties themselves.

The stocktake has been framed as a moment of reckoning, especially by those involved in the two-year process. UN Climate Change’s executive secretary Simon Stiell has described the GST as a “moment for course correction”, an opportunity to “bend the curve decisively on emissions” and as an “ambition, accountability and acceleration exercise”.

The US’ climate envoy John Kerry previously “expressed hope” that the stocktake and COP28 “will mark a chance to renew climate action”, Energy Monitor reported. Kerry is quoted as saying:

“A lot of interested parties around the world – whether NGOs, activists or companies – are no longer going to be impressed by repetition of previously announced things, or by sidestepping some of the realities of where we clearly now find ourselves.”

According to Farhan Akhtar, one of the co-facilitators of the stocktake’s technical dialogues, the process had the “broad participation” of all stakeholders: governments, experts and non-state actors. He stated:

“Across discussions, it was clear that the Paris Agreement has inspired widespread action that has significantly reduced forecasts of future warming. This global stocktake is taking place at a crucial moment to inspire further global action in responding to the climate crisis.”

While the stocktake’s synthesis report sparked headlines, the form of the final deal is a key question ahead of COP28.

Dr Jennifer Allan at Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics tells Carbon Brief that while the technical process has been “very inclusive” and has an “incredibly wide scope”, the format that its outcomes will take is “really uncertain…partly because the Paris Agreement and its rulebook are vague and silent on a lot of important issues”. These include a lack of clarity on how exactly the stocktake will inform the next set of pledges.

The stocktake is supposed to be in its political phase at this COP, but the text for a ministerial declaration is “nowhere near the level of completeness” for delegates to finalise quickly, warns Allan, stating that “it’s too late for a ministerial declaration, if that was ever envisioned.” This makes it likely that the outcome is restricted to a COP decision. She adds:

“For me, personally, this falls short of the type of political signalling that we need in order to ratchet up ambition. I think we’ll land at a short decision encompassing the few points on which parties agree.”

“What worries me is that there are many placeholders and calls for other agenda items to be brought in. If the GST decision becomes a dumping ground for other politically thorny discussions, like the mitigation work programme, then it will be very difficult to untie and land a solution. We may end up with something vague, which again could undermine its ability to inform more ambitious NDCs targeted to the priorities identified by the GST technical phase.”

The enormous variety and divergence in submissions and countries’ own wishlists for the final form of the deal – be it a target to double green hydrogen production or references to protectionism – make agreement in limited time seem unlikely.

Experts, therefore, welcomed the US-China statement and efforts to work with other countries towards consensus on a broad political GST decision, even if countries don’t see eye-to-eye on many, significant details.

For Indrajit Bose, climate change adviser at the Third World Network, the stocktake is an opportunity to “correct injustice”. Developed countries, he tells Carbon Brief, “must assume responsibility for this gap”, as they have “consistently failed to deliver their commitments under the Convention and tried to transfer the burden of their inaction onto developing countries”. He adds:

“They call for fossil fuel phase-out, but they have huge fossil fuel expansion plans. They speak of the importance of finance, but they have not delivered their past commitments and rely unrealistically on the private sector to do their job. Their hypocrisy knows no bounds.”

According to Bose, the argument by developed countries to end differentiation between developed and developing countries based on the fact that the world has changed since the first climate agreements in 1992 “rings hollow”. He explains:

“[I]n more ways than one, the world has not changed. There is still massive poverty and development needs in the global south. Regular climate-induced disasters are further exacerbating their challenges. The global stocktake must correct this injustice and developed countries must show leadership in climate action, engage in good faith and stop considering people in the global south as unimportant, second-class citizens.”

To Dr Lavanya Rajamani, professor of international environmental law at the University of Oxford, this stocktake is the “most consequential because it’s coming in the middle of the critical decade up to 2030” and provides a template for future stocktakes.

However, its actual outcome, she told Carbon Brief last month, “is not likely to tell us something we don’t know”. She adds:

“There are gaps in implementation, ambition, fairness and accountability. These have all been documented very well in the synthesis report of the GST’s technical dialogue. I think what we might see – which would be helpful – is ways of actually plugging those gaps. How do we get back on track?”

Rajamani believes there will be an emphasis on scaling up renewable energy, phasing out all unabated fossil fuels and that there will “need to be a strong outcome on finance and support countries to actually be able to do these things”.

While she hopes that there is a “strong follow-up process” embedded in the stocktake to inform new pledges in 2025, she believes there has been a “subtle shift” in the framing around target-setting following on from the stocktake.

Rajamani explains:

“I think there is a pivot towards focusing on implementation and understanding that implementation triggers iteratively increasing ambition. Ramping up pressure on states to just set target after target is like building a house of cards.”

The second important shift to Rajamani is that “equity and fairness have been reframed”, both in terms of systems transitions domestically, and between states, where green development can be seen as “something that fosters ambition rather than something that detracts from it.”

She adds:

“We’re not going to get to where we need to without engaging with a wider landscape of action and actors, and engaging with the idea of the stocktake and the Paris Agreement as trigger[s] and catalys[ts for] domestic policy shifts towards the transformations that we need.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.