The lack of labelling of plastic used in hospitals in the Philippines and Indonesia makes it harder for medical practitioners to understand whether medical tools are potentially harmful or recyclable.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Up to 72 per cent of the waste generated in five hospitals surveyed in these countries is plastic, 78 per cent of which is not labeled properly, revealed a report by Health Care Without Harm (HCWH), a US-based non-governmental organisation that works to reduce the environmental footprint of healthcare worldwide.

Hospitals in the Philippines generate an average of 4,600 kg of infectious waste per day, while general waste in hospitals reaches up to 6.5 kg for each hospital bed per day in Indonesia.

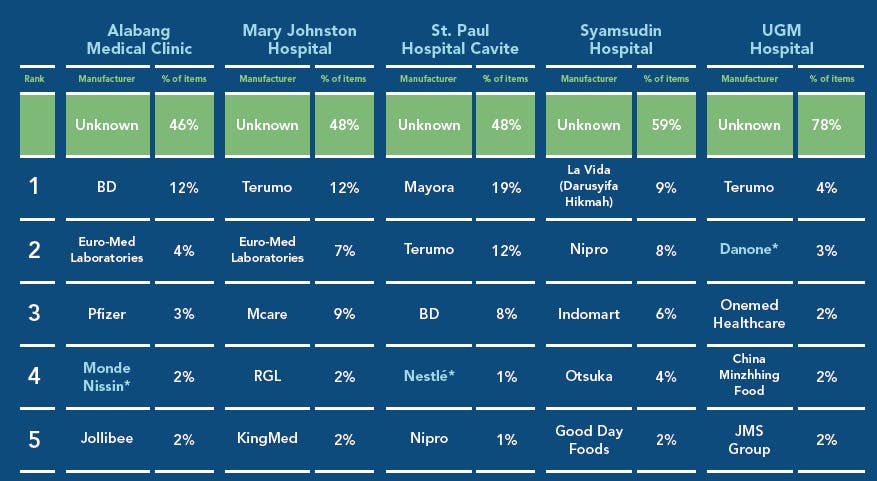

The hospitals surveyed were Alabang Medical Clinic, Mary Johnston Hospital, and St. Paul Hospital in the Philippines, and Syamsudin Hospital and UGM Hospital in Indonesia.

“

If plastics are labelled, hospitals can make better decisions based on the toxicity and recyclability of the medical tools they procure.

Faye Ferrer, environmental health consultant, Health Care Without Harm

“Healthcare as a professional institution needs to be informed of everything that it buys regardless if it’s plastic or not plastic. If the packaging for medication is toxic and enters your body it can be fatal,” Faye Ferrer, lead author of the report, told Eco-Business.

Ferrer said plastics like Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), commonly used in intravenous (IV) lines, blood bags, disposable surgical gloves, oxygen masks, and blister packs for pills, are toxic to the human body.

Plasticisers like diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), which are applied to these products to make them more flexible, are also harmful.

DEHP is classified as a reproductive toxin, which is linked to cases of femininisation of the male in unborn and newborn babies, where their genitals do not fully develop, said Ferrer.

Plasticisers can also damage the liver, kidneys, lungs, and the heart, she added.

Top manufacturers identified at each facility. *Company identified as major contributor to ocean plastics contamination. Source: HCWH

Ferrer, a plastics expert, said that hospitals contribute to damaging the environment if they do not know the type of plastics they are using in their medical tools.

While PVC is recyclable, it needs to be burned to be remoulded into new products, said Ferrer, and releases toxic human carcinogen chemicals like dioxin and furan that are harmful to people and the environment.

“Hospitals need to know which of the plastics they use are recyclable. Not all plastics are recyclable. Some of them are pseudo-recyclable but most probably end up in landfill,” she said.

“If plastics are labelled, hospitals can make better decisions based on the toxicity and recyclability of the medical tools they procure.”

Besides PVC, plastics used in medical supplies include Polypropylene (PP) and Mixed High Density Polyethylene (HDPE) to make syringes, and Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) in saline and other infusion bottles, according to the report.

PP and HDPE plastics have among the least toxic life cycles and are recyclable, it said.

Ferrer noted that while PET, HDPE and PP are highly recyclable, not all countries have the technology to recycle it. In the Philippines and Indonesia, PET is highly recyclable while other plastics are not.

Since hospitals purchase medical products in bulk, Ferrer urged them to demand manufacturers to use recyclable plastic.

Regardless of the size of the hospital, they have the leverage to impose their requirements when procuring their medical supplies, she added.

“There are no hospitals that don’t earn a profit. If these hospitals come together to work on procurement as one health system, they will have a bigger voice,” she said.