Within the real estate industry, sustainability certifications such as the Singapore-developed Green Mark have become widely accepted. But for architect Moshe Safdie, even if a building ticks all the boxes for a high-grade Platinum or Gold rating for its carbon abatement efforts or energy efficiency, this does not guarantee a better quality of life for the people who work or reside in it.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

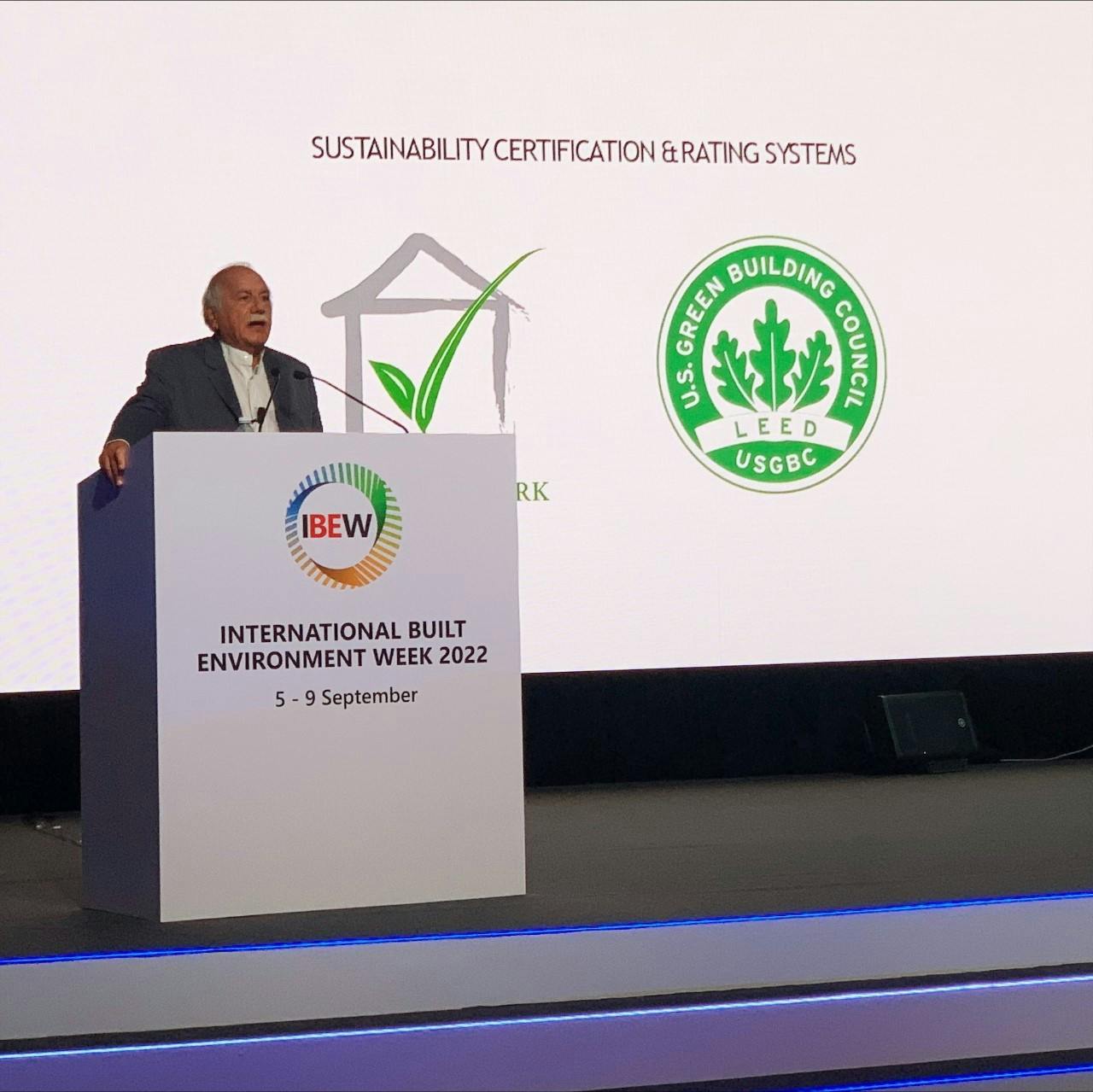

Speaking at a regional conference for built environment professionals in Singapore, in his first public lecture since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, Safdie called for architects to consider whether people have access to fresh air, daylight and green spaces, just as they would prioritise scoring high on “sustainability checklists”.

This is especially important in super-dense Asian cities, where urban and compact spaces are growing at a rate “more formidable than anything we have anticipated”, said the 84-year-old Israeli-Canadian architect-theorist, who has taken on several high-profile projects in Asia over the past decade, including Singapore’s Jewel Changi Airport and Marina Bay Sands.

“Today we all recognise sustainability as a major thrust for building projects. But I’d like to talk about sustainability, specifically in a way of what it does and does not do for us,” said Safdie, at International Built Environment Week 2022.

“As architects rally around the fashionable term, we have neglected another aspect of the environment: how quality of life is eroded as cities become mega in scale, denser as the years go by. It is driven by real estate forces, and we constantly face requests to increase the density of our buildings, and it becomes a vicious cycle. We need to put a lid on that.”

“

Workspaces need to be reexamined. After Covid-19, the attention towards better workplaces is now heightened. Previously, it had received less attention.

Moshe Safdie, architect

Showing a picture of an anonymous building project – one of a shiny skyscraper – that was awarded a platinum rating in a worldwide green building certification programme, Safdie said: “On paper, it meets all the requirements for environmental sustainability, and yet I would ask: To what extent does this express the quality of life for people working or living in the building?”

“Very little, I’d dare to suggest.”

In Singapore, the government introduced the Green Mark certification for landlords and developers in 2005, to help develop, assess and improve the overall environmental performance and carbon impact of buildings. The scheme was revised late last year to include more aggressive energy-efficiency standards and a performance-based recertification process.

Safdie stopped short of rubbishing the rating schemes, but said that as governments and policy planners regulate for sustainability in new buildings and retrofits, the same must be done to make sure that the spaces are liveable in some form of “code”, just as it has been done for sustainability.

Workspace revamp

For workspaces, one key criteria would be how far a work station is situated from a window, which would determine whether people get proper access to daylight and the exterior environment.

Safdie delivering his keynote lecture at a regional conference for built environment professionals. Image: Ng Wai Mun / Eco-Business

Speaking to Eco-Business after the keynote lecture, Safdie said that the Covid-19 pandemic exposed the flaws and vulnerabilities of cities, and how the spaces that we currently live in do not take into account “the fact that we might need to spend a lot of time in them”.

He is, however, against the idea of remote working. Human beings need to interact with each other. This is especially so in industries where creativity and communication is required, said Safdie.

His firm, Safdie Architects, is currently working on the Surbana Jurong corporate headquarters.

The campus offers over 740,000 square feet of space for 4,000 employees of the Singapore government-owned infrastructure and urban development consultancy, and is designed as a series of treehouse-like pavilions that attempt to integrate with the site’s existing green spaces and flora. It is Safdie’s response to and protest against office buildings with “zero outdoor and recreational space” – “working cells” isolated from their surroundings.

“Workspaces need to be reexamined. After Covid-19, the attention towards better workplaces is now heightened. Previously, it had received less attention.”

Safdie said that the same was done for the Jewel Changi Airport project. His team had attempted to recreate the sort of “hustle and bustle” one could experience in a bazaar with a central fountain, allowing people to “shop and eat, but as if they were in a park”, said Safdie.

Responding to a question on whether iconic projects like these would incur higher maintenance costs, Safdie said that a “Jewel Changi Airport without plants” would definitely be easier to upkeep. “But then it would just be a regular mall, and I question what that does for the quality of life for city dwellers.”

It is what people demand for their living environment too, said Safdie. “Those who can afford it would want a house with a garden. It might not be energy-efficient, but given the choice, they want that. So for architects, we need to rethink what that means for a dense city. Can we redesign the apartment or the building to create a garden for everyone?”