A few years ago, Southeast Asia’s energy transition got off to a bumpy start, and that’s putting it mildly.

While endowed with an extraordinary supply of wind and ample sunshine, governments across the region have long bucked the global trend towards renewables, despite it playing a key role in the fight against climate change.

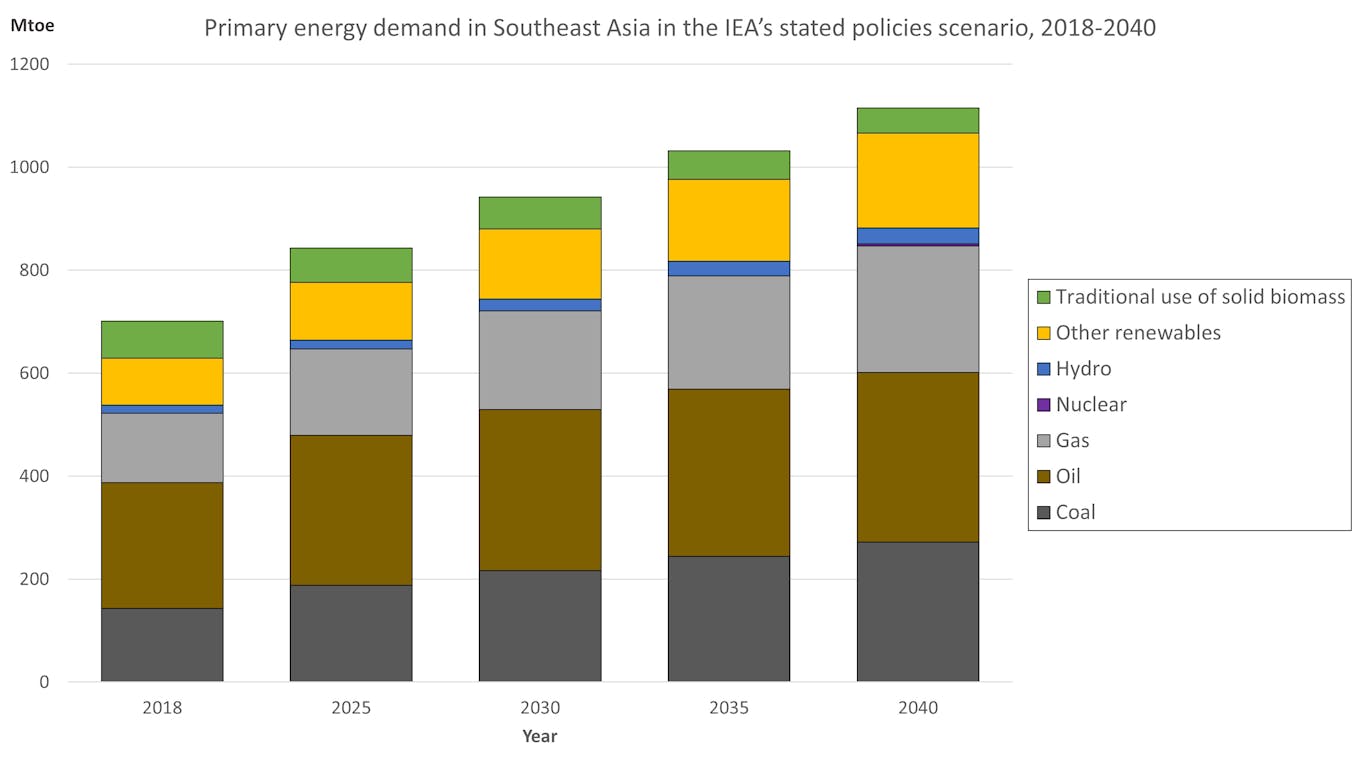

A bloc of some 670 million people, Southeast Asia may historically not rank among the world’s climate villains. But its population boom, along with burgeoning incomes and dizzying economic growth, is forecast to send energy demand rising by 60 per cent by 2040.

So far, the region—where some 45 million people still lack access to electricity—has handled the increase in power consumption primarily by doubling down on investments in planet-heating fossil fuels. If the world is to stave off climate catastrophe, this needs to change.

There are signs that Southeast Asia’s energy landscape is evolving. However, they are subtle, and the International Energy Agency (IEA) has warned that current power development blueprints will see the region remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels for decades to come.

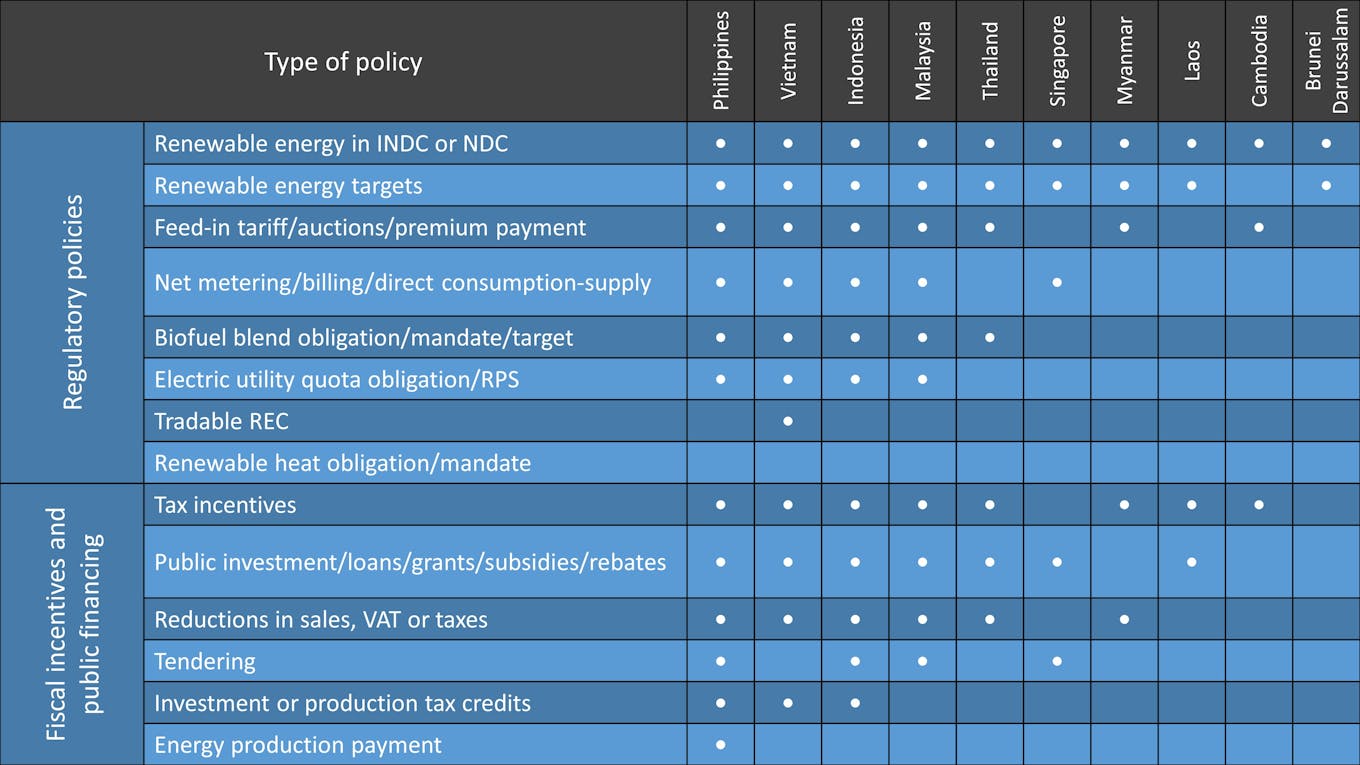

That is not to say that countries haven’t made any efforts at all. Over the years, governments have launched several programmes and policies to support the deployment of renewables, with varying degrees of success.

Take Indonesia. The nation first introduced feed-in tariffs—fixed, subsidised rates paid to clean energy generators for electricity they export to the grid—nearly a decade ago to attract foreign investment.

Similar schemes have helped to jump-start clean energy markets around the world, but not so in the archipelago, where wind and solar currently make up around 2 per cent of the power mix, with geothermal energy accounting for less than 4 per cent.

In the Philippines—an early renewables leader in the region—a different story unfolded, although the ultimate outcome has been no less sobering. In 2012, it too tried its hand at a tariff regime, but after a few promising years, progress in the market largely stalled.

With policies murky, foreign financiers began to walk away from the country, causing clean energy investment to plummet from US$1 billion in 2016 to US$0.16 million in 2018. Coal—the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel—now supplies more than half of the Philippines’ electricity.

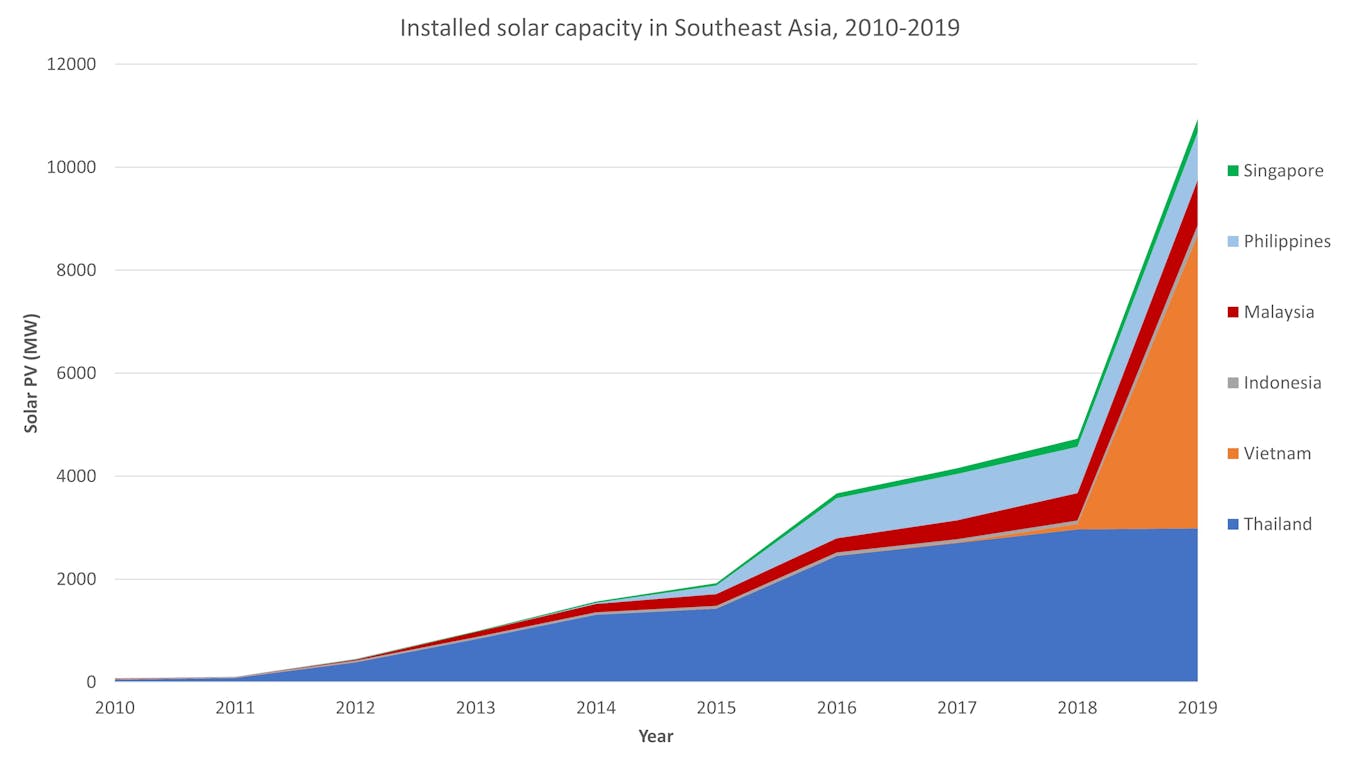

Even in Thailand, which was long touted as Southeast Asia’s renewable energy front-runner, regulatory uncertainty has in recent years deterred many new investors as competition from other markets such as Vietnam or Malaysia grows.

Eco-Business graphic: Primary energy demand in Southeast Asia in the IEA’s states policies scenario, 2018-2040. Source: IEA

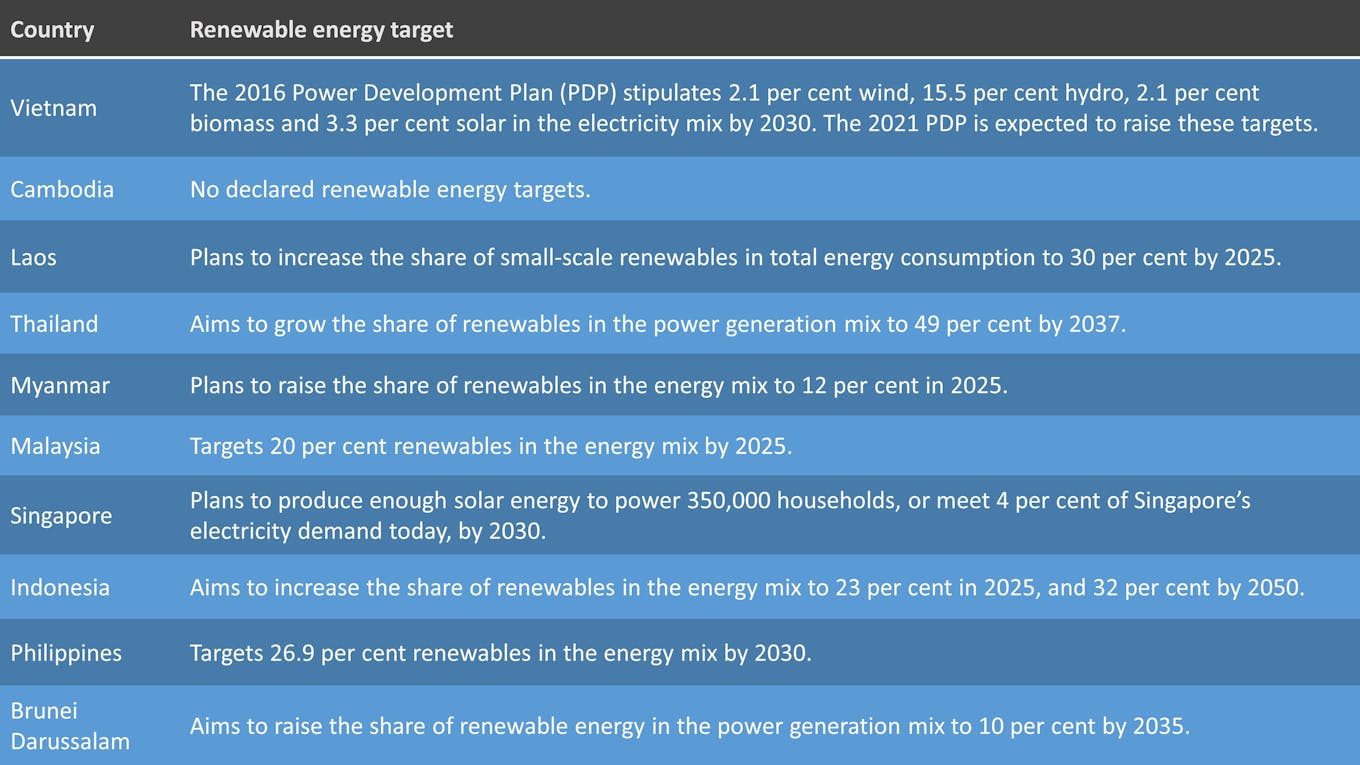

In 2015, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) established a region-wide target of sourcing 23 per cent of its primary energy from renewables by 2025, with most member states setting their own individual goals.

The Philippines, for instance, aims to raise the share of renewables in the energy mix to 26.9 per cent by 2030, up from less than 17 per cent presently, while Laos targets an increase in the share of small-scale renewables in its total energy consumption to 30 per cent by 2025.

But Southeast Asia is not on track to meet these goals. Coal, oil and gas are currently supporting 80 per cent of the energy demand growth, and in the absence of a central body that monitors progress, there are no political consequences for governments that fall behind on their targets.

Without a stronger policy push, the share of renewables in the energy mix is projected to stay flat at around 15 per cent through to 2025.

The IEA estimates that today’s energy plans could see the region more than double its coal-fired power capacity by 2040, at a time when coal use is in steep decline in most parts of the world.

Eco-Business graphic: Renewable energy targets in Southeast Asia

Change is afoot

Faced with entrenched interests of state-owned fossil fuel companies, adverse policies and unreliable regulatory environments, renewables have been fighting an uphill battle in Southeast Asia.

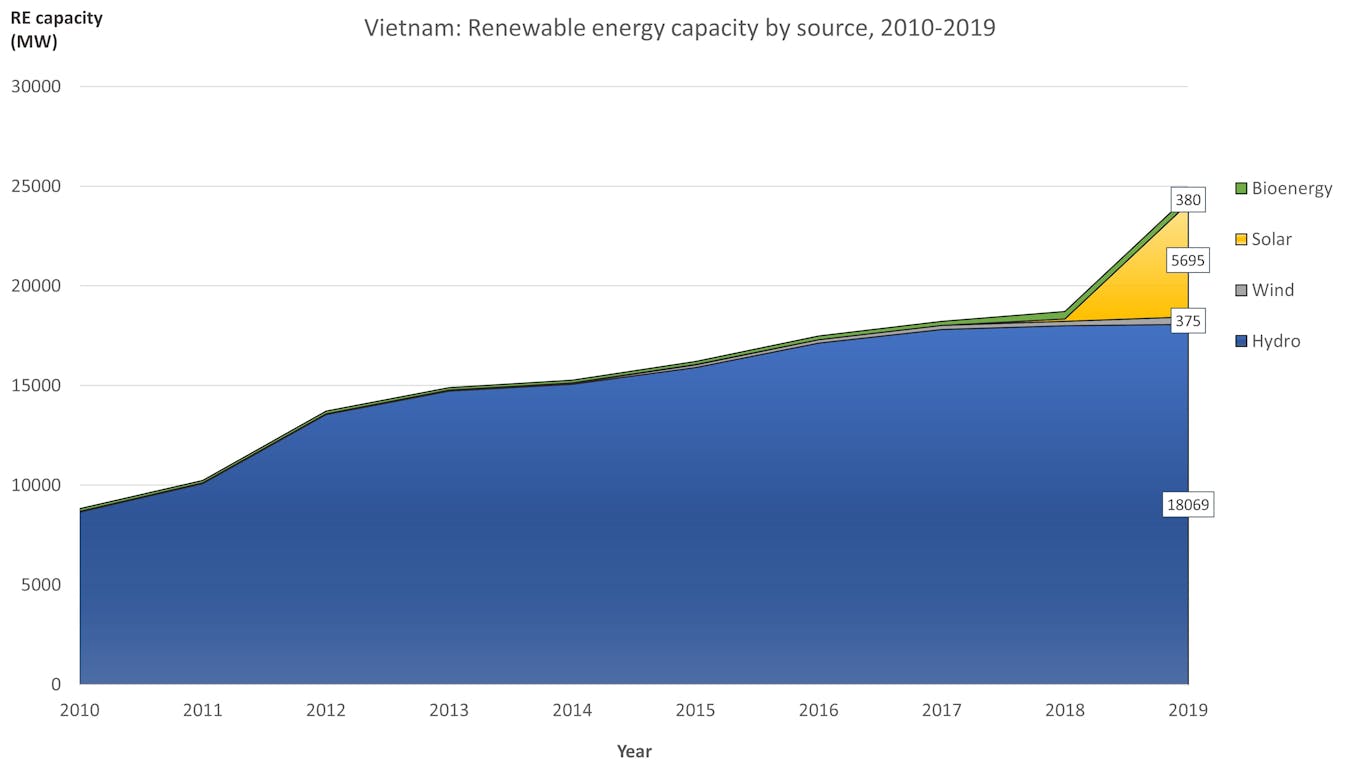

However, there are reasons for optimism, and the first one, clearly, has to be Vietnam. Over the past two years, the nation has performed a solar miracle, and by proving that well thought-out policies and ambition are all it takes for renewables to thrive, it has blazed a trail for its neighbours to follow.

Offered an attractive feed-in tariff and other fiscal incentives, developers rushed into the country to complete solar projects before a mid-2019 timeline. As a result, Vietnam’s photovoltaic power generation capacity jumped to a mind-boggling 5,695 megawatts (MW) last year, representing 44 per cent of Southeast Asia’s total solar capacity.

More than 50 times what Vietnam had installed in 2018, the capacity additions exceeded a solar energy target the government hadn’t expected to reach before 2025. The newly installed solar power was also much more than the national electricity grid could immediately handle.

Meanwhile, tremendous strides are also being made in Vietnam’s wind energy sector. In June, the government greenlighted 7 gigawatts (GW) worth of new projects, putting the country on track for a total wind power capacity of nearly 12 GW by 2025.

Eco-Business graphic: Renewable energy capacity by source in Vietnam, 2010-2019. The Vietnamese solar miracle has shown the region what ambitious renewable energy targets and a well thought-out industrial strategy can achieve. Source: IRENA

It wasn’t always that way. In fact, modern renewables played a negligible role in Vietnam’s power generation mix until recently. When the nation ran out of suitable sites for big hydropower dams a decade ago, it first turned to coal to ensure adequate power supply for its fast-growing economy.

To the dismay of environmentalists, coal power capacity in Vietnam rose by 72 per cent from 2010 to 2017. By 2018, the country had 32 GW of further coal projects under construction or planned, with a price tag of US$40 billion.

Financing, however, was proving increasingly difficult as ventures began to fall behind schedule and more investors ditched coal. According to Market Forces, an Australian non-profit that tracks fossil fuel investment, 57 per cent of planned coal power capacity in the country was delayed last year.

Worse still, experts began sounding the alarm over the risk that Vietnam’s existing coal fleet, with an average age of about 15 years, could be stranded assets by 2028 as clean energy costs fall, even as fears mounted that an overreliance on coal imports could threaten national energy security.

Amid such challenges, Vietnam has found the political will to propel structural change, starting what is set to be a fundamental reorientation of its power plans. After successfully using tariff schemes to lower the playing field for renewables, energy planners are now mulling a switch to an auction regime.

Auctions—which have resulted in record-low green electricity prices around the world—would enable Hanoi to select the most price-competitive developers for specific renewables projects, reflecting a global trend as markets mature and clean energy equipment gets better and cheaper.

Later this year, Vietnam is planning to launch a pilot programme—the first of its kind in the region—that will enable large electricity consumers to buy power immediately from generators through direct power purchase agreements. This means corporates keen to demonstrate their green commitments could soon become an additional driver behind the country’s clean energy switch.

Eco-Business graphic: Installed solar capacity in Southeast Asia, 2010-2019. Thailand was long Southeast Asia’s renewable energy front-runner, but progress in the nation has largely stalled. Source: IRENA

Building renewable energy markets from scratch is no easy task. All the more remarkable is how several nations across the region which previously lacked significant green generation capacity have recently kicked off immensely successful auction schemes. Vietnam is no longer the only beacon of hope for Southeast Asia’s energy transition.

Cambodia—the only Asean member state without concrete clean energy targets—may have not attracted much investment in renewables, but the solar auctions the country’s national electricity utility pulled off last year made many neighbours’ efforts look pale in comparison.

At US$0.03877 per kilowatt-hour (kWh), the tender of a 60 MW solar project resulted in the lowest photovoltaic power purchase tariff seen in Southeast Asia at the time. For other nations in the region adopting solar power auctions, Cambodia is now viewed as a model to learn from.

Then there is the sheer magnitude of the solar auctions held as part of Malaysia’s ongoing Large-Scale Solar (LSS) procurement programme. Launched in 2016, the scheme continues to defy expectations as the pool of bidders grows and electricity prices keep dropping with every round.

The third tender, held last year, was capped generation capacity at 500 MW but attracted 112 bids for more than 6.73 GW, underscoring the substantial developer interest in the Malaysian market.

Bids went as low as US$0.042 per kWh, beating even the rate for gas-based power in the nation. With a flourish, Malaysia’s energy minister announced that solar energy was approaching grid parity with fossil fuels.

To maintain momentum and help its battered economy back onto its feet, Malaysia quickly followed up with its largest auction to date this year, inviting bids for a total solar capacity of 1 GW.

In Myanmar, the government has started its own renewables revolution through its first-ever solar tender, calling for bids from developers for a staggering 1.06 GW of solar capacity. That’s more than 12 times the capacity it had in place last year.

In September, it was announced that the winning bids ranged from as low as US$0.0348 per kWh to US$0.051. Not only is this far below Myanmar’s average power generation costs, which stood at 8.1 cents in early 2018, but it also beats Cambodia’s recent auction record.

Eco-Business graphic: A comparison of renewable energy frameworks in Southeast Asia. Source: Asean Centre for Energy

Other countries are looking for a fresh start in their energy transition. The Philippines, for instance, will begin to enforce its Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) this year, marking a major milestone in its renewables journey that is expected to rejuvenate its ailing market.

The policy will mandate power distribution utilities to source an agreed portion of their energy supply from renewables, and to increase that share by 1 per cent every year until 2030 to guarantee a market for clean energy developers.

To facilitate compliance with the standard, the government looks to launch competitive auctions under its Green Energy Tariff Programme, which it hopes will add 2 GW of new clean generation capacity, although consultations on the proposal are still ongoing.

Experts predict the scheme will enable the Philippines to draw US$2 billion in clean energy finance in the coming decade. That’s cash badly needed after investment nosedived in recent years.

But with its electricity rates the third highest in Asia, the biggest benefit that the nation stands to gain from auctions is green power prices as low as PHP3 per kWh ($0.059), down from PHP9.45 per kWh in January.

Even in Indonesia, where adverse policies have made renewables directly compete with heavily subsidised coal, there is change underway.

Earlier this year, the nation released a new regulation that scraps its unpopular build, own, operate and transfer (“BOOT”) scheme—which required power producers to hand over their assets to the government once their contract expired and has often been cited as a significant barrier to developing renewables—to revive stalled clean energy ventures.

But the policy that would fix the pricing formula for renewables and offer further incentives to regain investors’ trust and put new projects on the table is not expected until later this year. With the improvements, the government anticipates clean energy investment to reach US$20 billion by 2024. Experts estimate that more is required to meet the government’s renewable energy target.

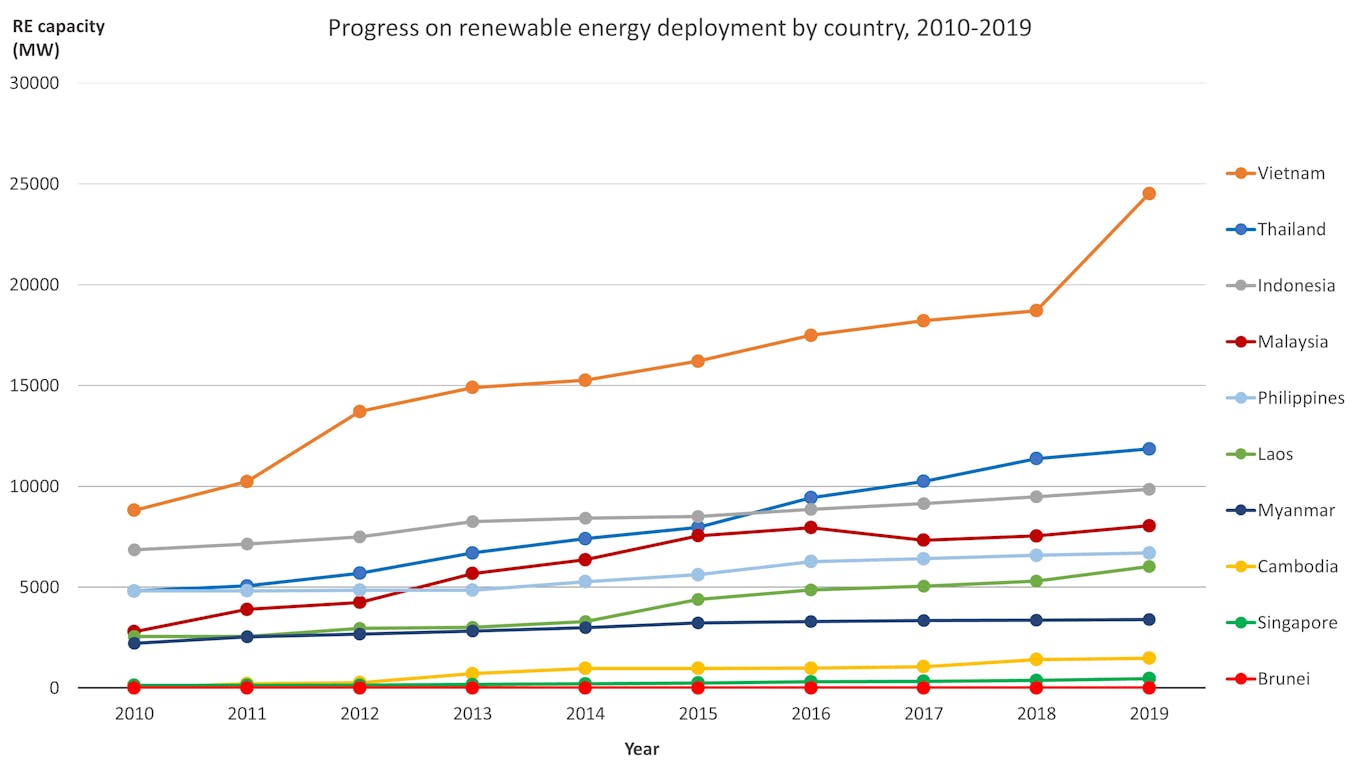

Eco-Business graphic: Progress on renewable energy deployment in Southeast Asia by country, 2010 to 2019. Source: IRENA

Declining clean power costs, as well as concerns over emissions and air pollution, have begun to alter the balance of future additions to Southeast Asia’s energy mix, a trend reflected in recent revisions to power development roadmaps that boost shares of renewables, typically at the expense of coal.

Thailand’s 2018 Power Development Plan (PDP), for instance, anticipates that coal power will make up 7 per cent of the generation mix in 2037, down from 14 per cent share in the previous document, while raising the share of renewables-based generation from 44 per cent to 49 per cent.

No nation is moving as fast as Vietnam, however. As thermal power development faces growing headwinds, the nation’s upcoming 8th Power Development Plan, due to take effect next year, is set to precipitate radical change and cement the country’s position as Southeast Asia’s renewables leader.

The blueprint—which is highly anticipated by developers, lenders, and environmental groups alike—is expected to stipulate a rapid expansion of renewables and gas and could see Vietnam scrap seven planned coal ventures and shelve six others at least until after 2030. Its latest development scenarios forecast that wind and solar together will comprise the largest share in its power capacity mix by 2030.

This ongoing shift in long-term planning is already visible in current project developments. In the first half of 2019, approvals of new coal power capacity across Southeast Asia were exceeded by solar capacity additions for the first time.

Much remains to be done

Such progress notwithstanding, Southeast Asia still faces an arduous journey ahead, with only five years left to run towards the regional renewables target and its energy transition at present not compatible with the Paris Agreement’s objective of keeping global heating well below 2 degrees Celsius.

Across the region, fossil fuels remain core to power plans, with some countries only just getting started. Laos—a nation notorious for its reckless pursuit of hydropower—has begun eyeing coal power exports as a means of spurring economic development, while Myanmar—where more than 40 per cent of the population still lacks access to electricity—expects coal will make up 30 per cent of the generation mix by 2030.

Even Vietnam—where coal consumption has tripled over the past decade—still plans to build 15 other coal plants with a combined capacity of 17.4 GW by 2024. Its coal pipeline remains Southeast Asia’s second-largest.

Meanwhile, the IEA predicts that oil will continue to dominate road transport demand in Southeast Asia, with the electrification of mobility making only limited inroads under current policies. This suggests little change from today’s traffic-clogged roads and filthy air in the bloc’s bustling cities.

Generous fossil fuel subsidies—worth US$35 billion in 2018 alone—remain a major obstacle to renewables across the region, which is home to three of the world’s 10 largest coal pipelines, and vested interests in fossil fuels continue to hold back green investment. As long as fossil fuels are subsidised, experts warn the playing field will not be level for renewables.

If Southeast Asia’s renewables switch is to accelerate, private money will be key. But to get financiers on board, governments have yet to hone policies and tidy up regulatory environments, states a new series of policy briefs by the Asean Centre for Energy, a Jakarta-based think tank.

Malaysia, for example, needs to draw an estimated US$8 billion of investment to reach its 2025 renewables goal, dwarfing the US$2.5 billion it attracted between 2006 and 2018. But with government support still firmly lying in gas, this may prove challenging.

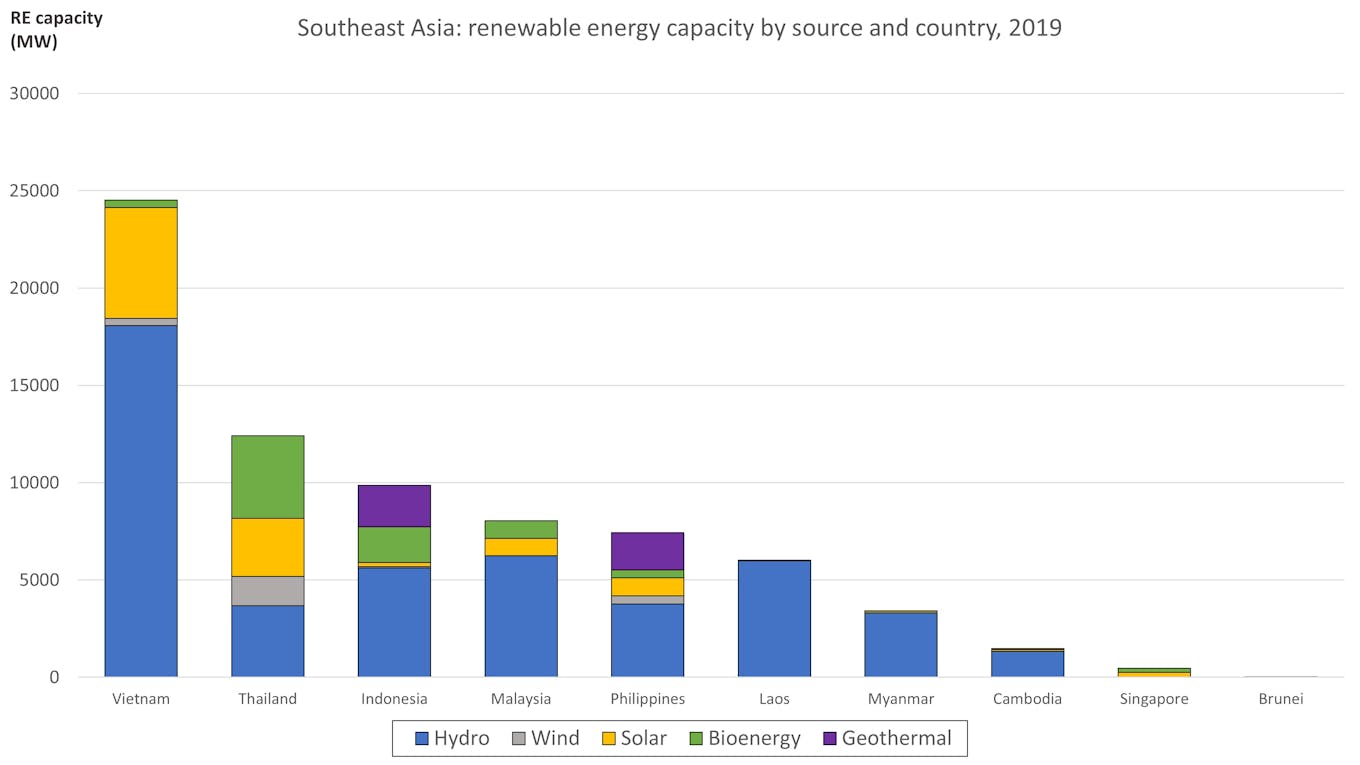

Eco-Business graphic: Renewable energy capacity by source and country, 2019. Source: IRENA

A weakness prevalent across the region is poor renewable energy governance. In Brunei and Indonesia, for instance, clean energy policies are implemented by smaller government bodies with limited resources and weak management capacity to govern the sector, leading to fragmented policy landscapes that scare investors.

Things don’t look much better elsewhere. Renewable energy governance in Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam falls within the scope of various ministries or government institutions, resulting in unclear responsibilities.

Worse even, power purchase agreements in Laos and Myanmar are still mostly negotiated on a case-by-case basis between energy ministries and developers, driving up costs for clean energy firms. Laos has yet to implement a pricing mechanism for renewables to attract finance, as does Brunei.

And while energy experts have stressed that Covid-19 offers an opportunity for an economic overhaul, only Malaysia and Myanmar have seized it—albeit much too timidly—by announcing new solar plans, according to a new report by environmental campaigners Greenpeace.

This is despite some clean energy technologies, like solar, being much faster to market than coal power plants, making them an almost immediate vehicle for economic development. Government spending on renewables has also been shown to create almost three times more jobs than coal and gas.

Singapore, where the share of renewables in the energy mix remains close to zero, is among nations that have shirked from a bolder environmental push and failed to ramp up efforts to tap unused renewable energy potential as part of their post-pandemic recovery.

This is even though a recent study by the Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore (SERIS) showed that solar energy has the potential to meet up to 43 per cent of the tiny island-nation’s electricity demand during the day, up from around 5 per cent currently.

Southeast Asian nations, however, won’t be able to keep resisting renewables forever. If the prospect of reduced emissions, improved energy security, cleaner air and plunging clean energy prices does not sway governments, what will?

As renewables success stories continue to emerge from the region, countries that have seen poor progress have little excuse for not having a working green energy market design in place. There are plenty of neighbours to learn from.

This report is part of Eco-Business’s series on Southeast Asia’s clean energy transition, which highlights the opportunities and roadblocks on the region’s path to a renewable energy future.