A survey by United States-based law firm Morrison Foerster has found that weak sustainability ratings are not necessarily dealbreakers for Asia-headquartered funds.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The annual Asia Funds ESG Survey – first launched last year and co-published with Asian private equity and venture capital intelligence provider ACVJ – showed that only 23 per cent of respondents have pulled out of deals after problems with their environmental, social and governance (ESG) track record were raised after doing due diligence.

But over 90 per cent of general partners (GPs) – that is, the firms that manage private equity funds – expressed confidence in improving the sustainability practices of businesses with neutral or negative ESG credentials after including them in their portfolios.

“When their due diligence process identifies these issues, they don’t put up their hands up and say ‘forget it, we can’t invest,’” said Marcia Ellis, a global co-chair of Global Private Equity Group at Morrison Foerster, who is based in Hong Kong.

“A lot of the funds we are talking to see this as an opportunity. First of all, they can use this problem to negotiate for a better price for the company. Once they take over and have a strategy for turning around bad ESG issues, they can increase the value of the company, and either list it or make a secondary sale at a higher valuation.”

Examples of sustainability-related issues could range from being a known polluter with higher carbon emissions compared to industry peers, to lapses in labour policies for a company that operates a lot of factories.

The study this year aggregated responses from 100 Asian funds each with at least US$1 billion in assets under management, which included private equity funds, credit and special situation funds, sovereign wealth funds, insurance asset managers and pension funds.

By geography, 35 per cent of respondents were based in China and Hong Kong, 25 per cent in Japan, 15 per cent in India, 15 per cent in Southeast Asia and 10 per cent in the rest of Asia, including Taiwan and South Korea.

Exclusion policies ‘generally out of favour’

In Asia, a growing number of financial institutions – which are increasingly subjected to mandatory ESG disclosures – now have exclusion policies to reduce their portfolio exposure to companies with high stranded asset risks or engaged in business activities deemed harmful to society.

For instance, the number of financial institutions with coal exclusion policies in this region has jumped from 10 between 2013 and April 2019, to 41 in the three years that followed, according to the think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

As banks and big energy companies divest from their dirtiest assets, private equity firms are snapping them up and operating them in private markets, which are less regulated and exempted from most mandatory disclosure requirements.

For private equity funds, exclusion policies are “generally out of favour” given their focus on value creation, meaning they will invest in any industry where they can add market value, said Ellis. “Exclusion policies just tend to eliminate. But value creation is about turning around a bad polluter and making it a more environmentally friendly company.”

Ellis added that since many limited partners (LPs) – the pensions funds, hedge funds and other institution investors that provide capital for private equity firms to invest – of Asian-based funds are pension funds in the United States, they are more cautious about exclusion policies amid the backlash that ESG has faced in the country.

But Ellis acknowledged that in some cases, it is clearly “not a sensible decision” to acquire a company, if it has been or is likely to be found in breach of local laws, as there will be no “economically feasible” way to overhaul its ESG credentials.

ESG increasingly a driver of value creation

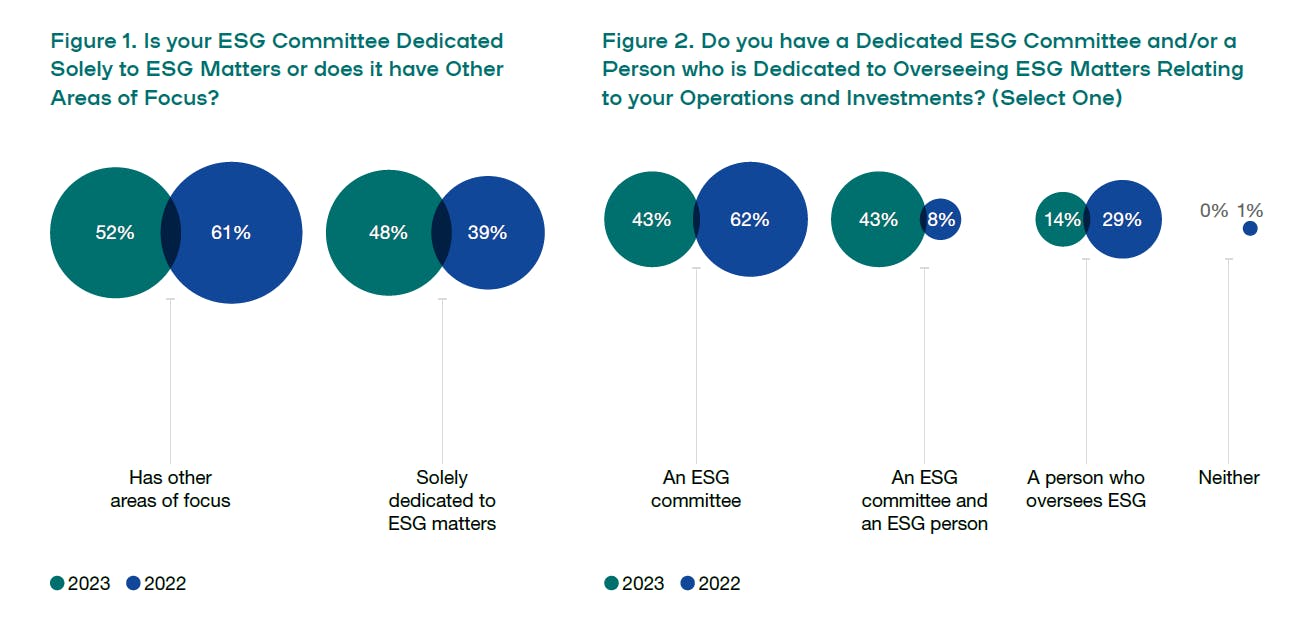

Asian private equity funds appear to have devoted more resources to sustainability over the past year, with some 43 per cent reporting they now have both an ESG committee and an ESG specialist on board, a marked increase from just 8 per cent last year.

Sustainability committees are now in place at 86 per cent of Asia-based funds. They are also increasingly focused, where 48 per cent of respondents said the committee is dedicated solely to sustainability issues, up from 39 per cent last year. Source: Asia Funds ESG Survey 2023

These funds could also support portfolio companies lacking the capital to invest in software systems for collecting, analysing and reporting climate-related data through the transfer of technology and knowhow, said Ellis.

For example, Hong Kong-based Affinity Equity Partners – one of the private equity firms featured in the report – guides all its portfolio businesses through the process of measuring their Scope 1 and 2 emissions as part of the ESG Data Convergence Initiative, a private equity coalition providing industry benchmarks for ESG metrics as well as the integration of Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)’s recommendations.

Sarah Pang, head of ESG and sustainability for Affinity Equity Partners, which has about US$14 billion of assets under management, cited how one of their portfolio companies, airport lounge operator Plaza Premium Group, managed to win a bid for a net zero lounge that launched in Helsinki airport after they worked with the group to track its emissions.

“A lot of the more interesting stuff happens after the investment period on the asset management side, when you’ve acquired the company and you’re figuring out how to work with it to increase its valuation by improving its ESG metrics and making it more competitive than its peers,” said Ellis.

But even as Asian funds have begun to recognise the importance of integrating sustainability into their investment process, the study suggested that most still yet to see it as a “core driver” of value creation. Just 17 per cent of respondents have linked their investment team’s compensation to the organisation’s ESG targets.

Continued push for greater accountability

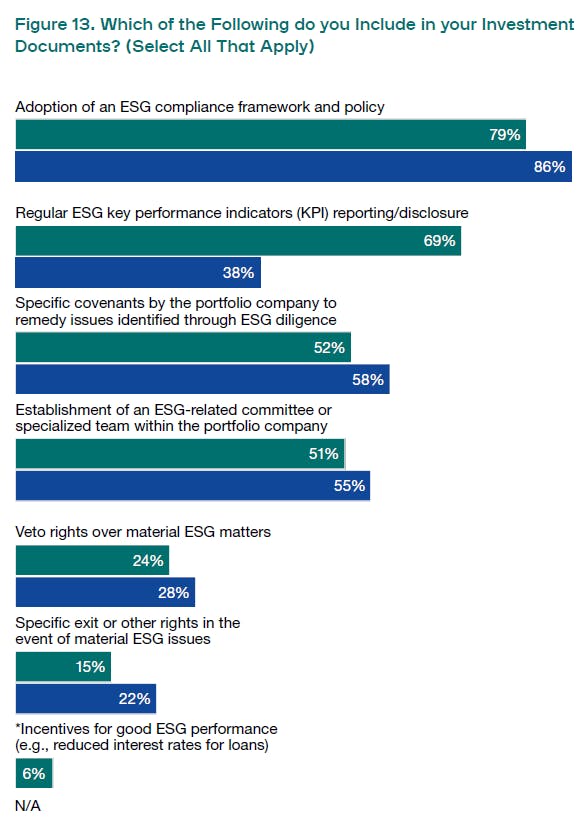

The study showed that holding portfolio companies accountable for sustainability concerns through the inclusion of clauses in investment documents continued to be a focus for investors in Asia. Over three-quarters of respondents said they sometimes, if not always, require clauses regarding ESG compliance.

The most popular clauses that Asia-based private equity funds included in investment documents to hold portfolio companies for sustainability issues. Source: Asia Funds ESG Survey 2023

Some popular clauses are the adoption of an ESG compliance framework, regular reporting against key performance indicators on sustainability and taking action on issues identified through ESG due diligence.

There is increasing scrutiny over sustainability-related claims in Asia. In January, South Korea became the first jurisdiction in the region to draft an anti-greenwashing law that punishes companies for false or exaggerated green claims with a fine of up to US$2,300. This has led to increased awareness about greenwashing risks.

70 per cent of respondents now have policies regarding the sustainability communications of their portfolio businesses, up from 54 per cent in last year’s results.

For now, green hushing, the practice of hiding green credentials from public view to evade greenwashing accusations, seems to be a bigger threat among Asia-based funds. Over 66 per cent of those surveyed have green investment practices, but less than half of this group are actively promoting them.