Last week, the geo-political showdown between the United States and Iran incited fears of an imminent World War 3, as observers kept their eyes glued to a long-awaited exchange of hostilities. However, although a full-blown war might not yet be on the horizon, tensions are brewing in more places across the world due to one crucial reason: water.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

According to data from California-based thinktank Pacific Institute, incidents of water-related violence have doubled in the last ten years, with disputes and protests erupting in countries such as Iran, India and Iraq.

In a bid to measure the risks posed by water-related challenges and pre-empt conflict, a consortium of researchers have developed a new tool that combines machine learning and different types of data — environmental, meteorological, social and economic — to forecast where conflict is likely to break out.

Called the Water, Peace and Security (WPS) Global Early Warning Tool, WPS combines climate data, socio-economic variables and local drivers such as governance and pre-existing conflict “to intervene and help defuse conflicts before blood is shed.”

In 2018, anger towards the government flared over acute water shortages and pollution in Iraq, after over 100,000 people were hospitalised due to reasons linked to poor water quality. When protests broke out, demonstrators were killed in clashes with security forces, adding fuel to the fire.

Elsewhere, the Colorado basin in the United States has been identified as a “hotspot” area where demographic and climatic conditions have increased hydro-political risk between states, while researchers are still studying the link between Syria’s prolonged drought to its devastating civil war.

While previous early warning tools focused on purely political and socio-economic factors, the WPS tool considers specific variables such as rainfall, water scarcity and crop failures, as well as risks from climate change. For instance, data on crop health helps paint a fuller picture of how likely conflict will break out in a community facing other vulnerabilities, such as poverty and ethnic discrimination.

“Some of the potential conflict areas are water-related, others are not — additional research is needed to confirm. Once high-risk areas are identified, the international community should have rapid response teams in place that can offer assistance to at-risk countries,” said Charles Iceland, director of the Global and National Water Initiatives at non-government organisation World Resources Institute.

“These teams can help regional, national, state, and local leaders better understand the nature of the problem, the major drivers and potential ways to address the problem,” added Iceland, who was part of the team that designed the conflict prediction tool.

“

According to the Water, Peace and Security early warning tool, 2,000 administrative districts across the Global South are currently at risk of water-related conflict.

Which parts of the world are most vulnerable?

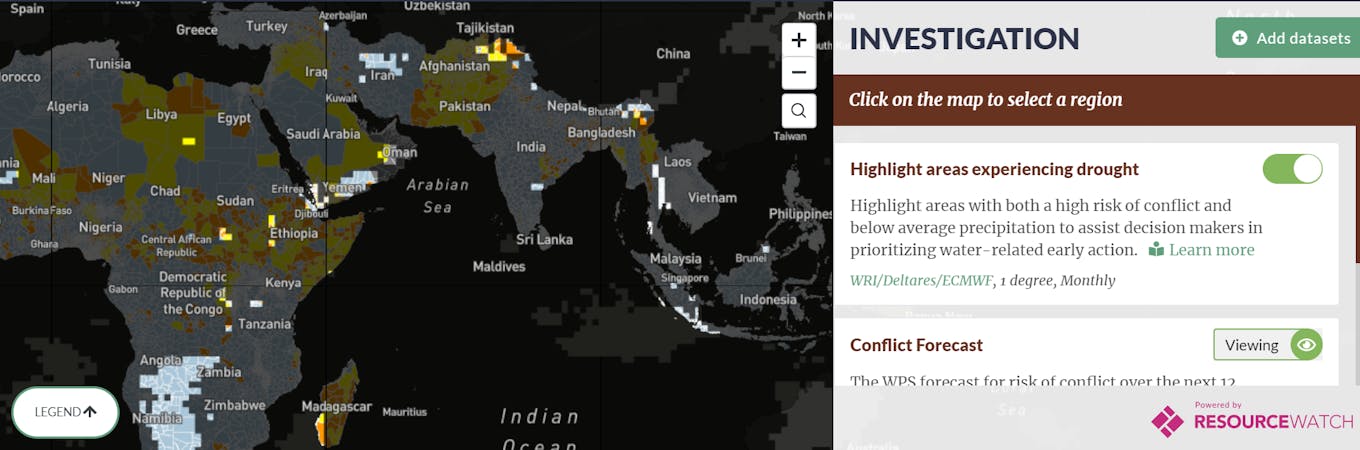

The WPS tool will identify potential hotspots across Africa, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia over the next 12 months, by comparing data collected over the past 20 years.

According to the tool, 2,000 administrative districts across the Global South are currently at risk of water-related conflict, including Iraq, Iran, Mali, Nigeria, India and Pakistan. In Southeast Asia, local conflicts have already broken out in Myanmar due to dam-building activities, while contentious issues related to the transboundary Mekong River have the potential to affect communities from China to Cambodia and Laos.

The Water, Peace and Security map is the first predictive tool that brings together environmental and traditional socio-economic data to help prevent conflict from breaking out over water-related challenges. Image: WPS platform

However, the region has so far been spared full-fledged water conflicts due to the abundance of water in relation to other parts of the world, as well as to some extent better governance structures, said Schmeier in an interview with Eco-Business.

She added that climate change might, however, change this.

Already in India, water mismanagement, unregulated use of groundwater and rapid urbanisation coupled with erratic weather conditions have made daily life more challenging and stripped people of their livelihoods. In Chennai, conflicts at water collection points occur almost daily, Eco-Business reported last year.

In a 2013 Harvard University study, researchers noted that weather and climate extremes can influence hostile interests in places such as Mali and Somalia, where the rise of violent groups such as Al-Qaeda can be linked to long-lasting drought and the weakness of the state in safeguarding water services and infrastructure.

So if water can trigger or exacerbate conflict, why has it taken so long for governments to act on solutions to local water issues?

“While the importance of water has long been acknowledged by the water management community, other policy communities — in security and diplomacy for example — have not been aware of it, or have shied away from the matter as it is complex and entangled with many other issues, including national security considerations,” said Scheimer.

He added that recent conflicts and migration flows out of the Inner Niger Delta and the Lake Chad Basin in Western Africa have prompted policymakers to think about the issue.

“This is even more so the case as we now already see the impacts of climate change in these regions, such as prolonged droughts, and can only expect them to worsen, increasing the pressure to act,” she added.

Ladies carrying water back to their home in Somalia. Reports say that conflicts in Somalia, Yemen and Syria have their roots in unusual and exceptionally long droughts. Image: riy, CC BY-SA 2.0

The myth of water wars

In 1995, former vice president of the World Bank Ismail Seragaldin predicted that “wars of the 21st century will be about water unless we change the way in which we manage it.”

His forecast inspired alarming headlines on the future of “water wars” in which water stress and scarcity would fuel inter-state and national conflicts. Although wars have not yet erupted over water, conflicts on the sub-national and community level reflect how sensitive water issues are.

“Nations see the strategic advantages and challenges of water on a grand scale. But human beings experience issues of water supply—both availability and quality—at an intensely personal level,” wrote political scientist Thomas Bernauer in 2018.

Iceland also added that water-related challenges should not merely be seen as a reason for conflict, but the cause of other global challenges such as destabilising migration, cities reaching Day Zero, famine, or water-related disease outbreaks like cholera. For example, in 2017, nearly 19 million were internally displaced by extreme weather events — including drought and flooding — as compared to 12 million people displaced by violence and conflict.

“The future of water seems inextricably linked to conflict and competition. But focusing solely on the conflict risk of water can undermine the very solutions that address those risks. Such an approach puts the military and security community in the drivers’ seat — to the detriment of other key partners,” noted Bernauer.

Scheimer added that countries competing over water resources typically find that engaging in conflict brings a lot of negative repercussions in terms of deteriorating diplomatic and economic relations, economic costs and the loss of international reputation, which puts them off waging a war over water.

“While water is often the source of tensions, it is also a source for peace. Water — by its very nature — requires cooperation for its management and is a resource typically creating win-win-solutions if managed correctly,” she said.