Joy Belmonte was digging for signs of the human past when politics beckoned.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

She had just returned from the United Kingdom where she did a master’s degree in archeology, and was teaching museum studies and the history of archaeological theater at the University of the Philippines.

It was not so much that she was the daughter of influential parents – former speaker of the house of representatives and Quezon City mayor Sonny Belmonte and the founder of two of the Philippines’ biggest newspapers, Betty Go-Belmonte – that pushed her towards public service. It was being told by a previous mayor of Manila that she would not be granted an excavation permit because archeology was “irrelevant”.

“Not a lot of women did archaeology, and that was really my dream. I was not at all interested in politics, but I realised that if the opportunity presented itself, it might be a good thing [to run for office],” Belmonte told Eco-Business.

“I didn’t want what happened to me happen to other people who want their voices to be heard. Part of that experience really impressed upon me that we lacked leaders who gave consideration to issues other people felt were important.”

As soon as her father finished his term in office in 2010, she ran for vice mayor of the most populous city in the Philippines. She won. Nine years later, she became the city’s first elected female mayor. Gender equality, enhancing social services for the marginalised, and better waste management have been key areas of focus during her time in office.

In this interview, the 54 year-old politician tells Eco-Business how she has used her environmental advocacy to put Quezon City on the map as an Asian metropolis fighting plastic pollution and climate change.

Tell us about when you first became an advocate for the environment.

I always trace it back to 2009, when Typhoon Ketsana [the second most devastating cyclone of that year] struck Metro Manila. My dad was the mayor of Quezon City then, and that was the first time our city and our country experienced sustained rains lasting about three days. There were massive floods all over our city and we had never experienced anything like that.

My father and the local government officials were at a loss as to how to handle the situation. I distinctly recall that when the floods subsided, the city was dealing with so much plastic on trees, roads, and sewers. It was a horrible sight. It was then that I realised how destructive plastic pollution is, and I wanted to combat it if given the opportunity.

Residents of different districts in Metro Manila seek refuge inside the Santo Domingo church in Quezon City, due to floodwaters from Typhoon Ketsana in 2019. Image: Veejay Villafranca/ Greenpeace

How did you introduce the ban on single-use plastic to a city known to be the biggest waste producer in Metro Manila?

When I was elected vice-mayor, we started by passing an ordinance to reduce plastic bags use [stores were required to must display a sign to encourage consumers to bring their own recyclable or reusable bags.

We thought that drastic regulation to ban plastic bags might not work. It’s a mindset change that we were trying to achieve. When we got people convinced, or at least prepared to bring their own eco bags, we could see a gradual behavioural change until such time that we felt people were ready for a complete ban on plastic bags.

[When I became mayor], we banned all single-use material, including paper, not just plastic, because we wanted to reduce the volume of litter in the waste stream.

Paper and plastic for recycling are deposited by residents at a drop-off boooth, in exhange for “environmental points”. Image: QC Government

How did the “Trash to Cashback”, an initiative that allows residents to exchange recyclables for basic necessities, come about?

It really started as one of our ways of addressing the effects of the pandemic. So many people had lost their jobs, or were displaced. At the same time, the collection of garbage was irregular, or not being segregated at source which used to be our practice in the city.

We decided on this incentives programme, where you can trade in recyclables like paper, metals and plastics to get “environmental points” that you could exchange for basic necessities like eggs, rice, and vegetables. Since people were in need of food and most had lost their jobs, it was something that was very important to them.

The programme has collected around 300,000 kilogrammes of recyclable and single-use plastics and diverted it from landfill and upcycled it to useful products since its launch in 2022. What’s next?

We want to move on from having to incentivise people to segregate their waste for recycling. At the end of the day, it should be your mindset to segregate waste, because it’s the right thing to do, regardless of whether you will receive any kind of incentive. The programme works because people are trading in their recyclables left and right, but at the end of the day, the goal is to be able to segregate at source, recycle, reuse, and reduce your waste without incentives.

The “Kuha ka sa tingi” project was a partnership with Greenpeace where the QC government established refilling stations on exisiting sari-sari stories to help addrress plastic pollution crisis. Image: QC Government

What has Quezon City done to address sachet culture?

We piloted a project with 30 sari-sari stores [small neighbourhood shops] to install refillable containers to dispense an unbranded liquid detergent, dishwashing liquid, fabric softener and all-purpose cleaner. To be honest, I was not excited about it because I wasn’t so sure it was going to work. But the pilot was a success which showed me that Filipinos are not brand conscious when it comes to these products at least.

We were able to document 47,000 sachets being diverted from the waste stream. But the most important insight for me is the fact that people are not brand conscious. So we can go back to manufacturers to say, ‘If you don’t shape up and change your packaging or cooperate with us environmentalists to prepare or design something that is more reusable, we have evidence to show that your loyal customers are going to leave you the more we implement this project.’

I spoke to Senator Loren Legarda who is already a top environmentalist and she said none of the manufacturers are answering her calls to sit down to help solve this problem.

This year we’re going to install refillable systems in another 5,000 sari-sari stores, and hopefully we’re able to roll out just enough so that manufacturers feel the pinch. About 60 per cent of their sales come from sari-sari stores, so if we put a dent in their balance sheet, maybe they might be willing to sit down and talk.

The Quezon City climate change and environmental sustainability department replaces ozone filters in air quality sensors and automated weather stations across the city. These devices gather data for developing clean air interventions to improve the city’s air quality. It was among the reasons why Quezon City earned a spot on the CDP’s A-list from more than 900 cities evaluated in 2023. Image: QC Government

Aside from plastic recycling schemes, Quezon City has been recognised as one of the 119 cities globally leading the charge against climate change by international non-profit CDP. Why is it important for cities to be at the forefront of sustainability issues?

Whether you belong to a city or the national government, a developed country or a developing country, it is your responsibility to be part of the solution to the climate crisis.

Many people say, we [the Philippines] contribute the least to the problem, so why should we be involved in such solutions? Let the developed countries come up with solutions. I feel that it’s such a cop out [to do so]. It’s a nice message to send to the world that we are the least or one of the least contributors, but we are working much harder than you, developed countries, to solve this problem. They should be ashamed and do their part.

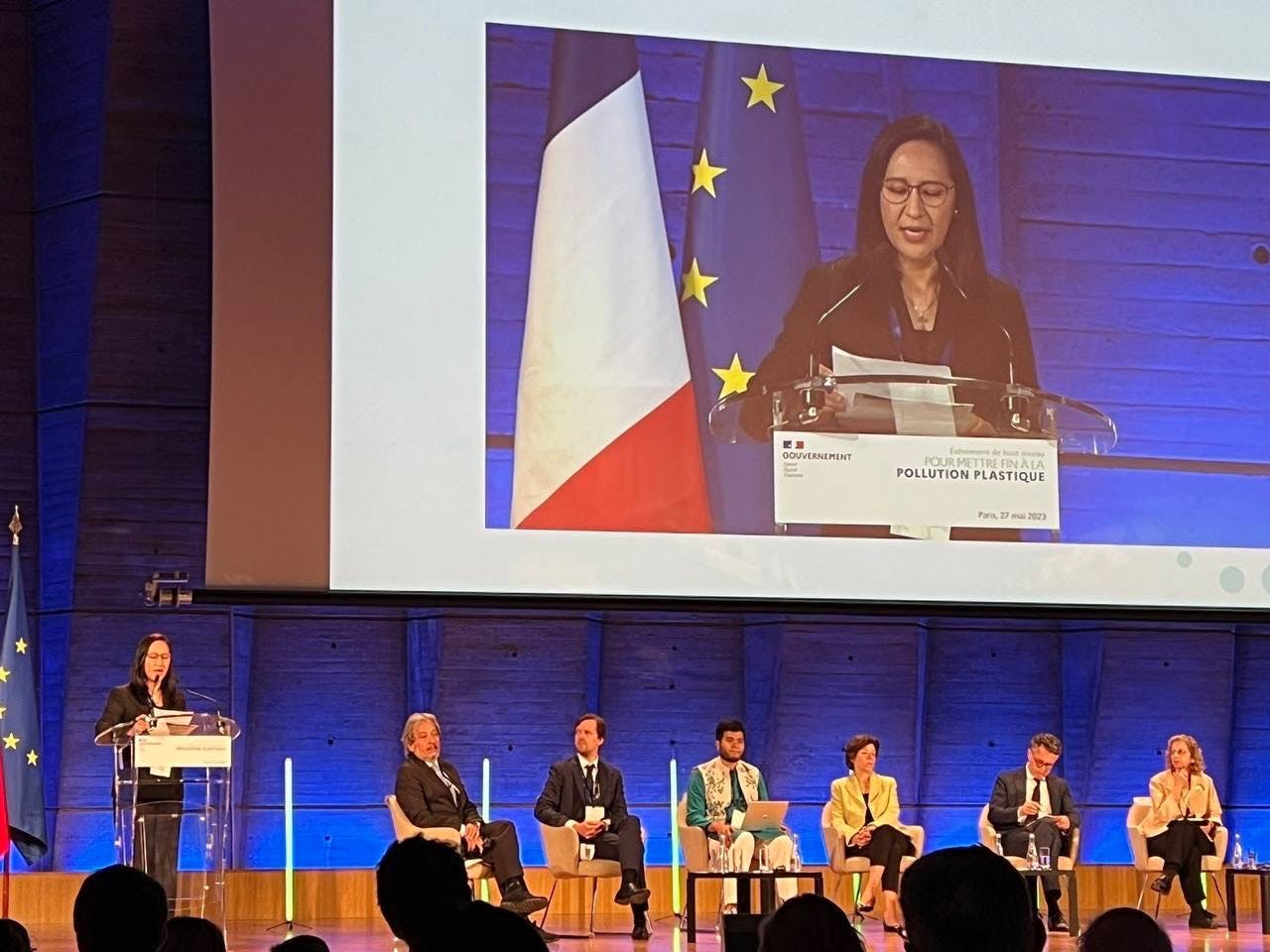

Quezon City mayor Joy Belmonte represents city leaders from around the world as she delivers a speech in front of the high-level UN Treaty on Plastic Pollution in Paris, France on 27 May 2023. Image: QC Government Twitter page

You were at the United Nations Global plastic treaty negotiations second session in Paris in May last year. Tell us about your experience.

Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo held a session where she invited mayors from around the world to talk about the plastics issue. I was proud, coming from the Philippines, which is known for other [negative] things. If my city can be that city that will bring a more positive image for our country, then why not?

The next day, I was selected as the mayor to represent the city perspective at the treaty. It was nerve wracking because everybody else there was a big-time academic, all these important people, and then there’s me as the only Asian there. We were fighting for cities to be heard in the conversation about plastic pollution. Change happens fastest at the city level.

What are your thoughts on the UN global plastics treaty? Critics have highlighted the low ambition of some countries and point out that the process has been influenced by major plastic producers.

I think that more determined, high ambition cities or countries, really have to go out and be more aggressive and fight for a majority vote, rather than a consensus.

I’m not suspicious if big corporates are involved because they have to be active. Just because they are active does not mean they want to delay the process. What they’re fighting for is for it to be a coordinated effort that involves everybody.

If some are committed and some are not, then there is no level playing field. Some countries are pushing for a voluntary (treaty) but what we need is a strong, legally binding, mandatory document where we have to be compliant, otherwise it won’t work.

What’s been the most difficult challenge you’ve faced over the past 12 months?

It is frustrating in a sense that we want to move faster in terms of climate solutions, but we cannot because we are constrained by a lack of resources. Despite all our campaigning for climate finance in international venues, there are not enough lenders. Even if there are those who are willing to lend like the World Bank, [who tell us] we can borrow from them to convert all our buses to electric or scale up our solar panels, their interest rates are still too high. There is no scheme to help us speed up our work.

Quezon City may have the perfect climate change action plan, but we have made the rounds in asking donors for funding and there are still a lot of “no’s”. But we can’t stop there. We just have to make do with what we have. Like this year, we are going to transition one bus to electric where one route is a free ride. Every year, our aim is to launch one electric bus to complete the eight bus routes in Quezon City.

How can you convince Filipinos that not all politicians are corrupt?

Before you can rally the people behind you and the causes that you fight for, you have to win their trust and confidence.

We have already garnered more than 250 recommendations since we got into office. We have been recognised for various services, from the best jail to the best veterinary service. But my favourite accolade is the three straight years where we got ‘clean opinions’ from the Commission on Audit (COA). [The COA is the supreme auditing arm of the Philippine government. A clean opinion means that the municipality’s financial statements are free of error, fraud, irregularity and are properly maintained.] No mayor of Quezon City has ever been given even one clean opinion.

This proves to the people that their government is using taxpayers’ money wisely, that the projects that they’re spending your money on are sound and good and they go back to the people. Every time we get that clean opinion, I give a bonus of P10,000 to the employees of city hall. That is the one recommendation that I would like to sustain until the end of my term. It proves the government can be trusted so when I say, ‘Come on people, stop drinking from your PET bottles and bring your own water bottle’, they will do it because they believe in me. If your credibility is sound, that for me is the best endorsement as a leader.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Joy Belmonte was one of 10 sustainability leaders selected for the Eco-Business A-List 2023. Read our stories with the other winners here.