The first-ever global data platform to map out dredging activities finds that the growing pace of marine sand extraction, driven by Asia, is nearing the natural sand replenishment rate needed to maintain vital marine ecosystems.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The marine dredging industry extracts six billion tonnes of sand from the world’s oceans each year, or the equivalent of a wall of 10 metre high by 10 metre wide around the Earth annually, according to the new United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) data platform Marine Sand Watch which launched on Tuesday (5 September).

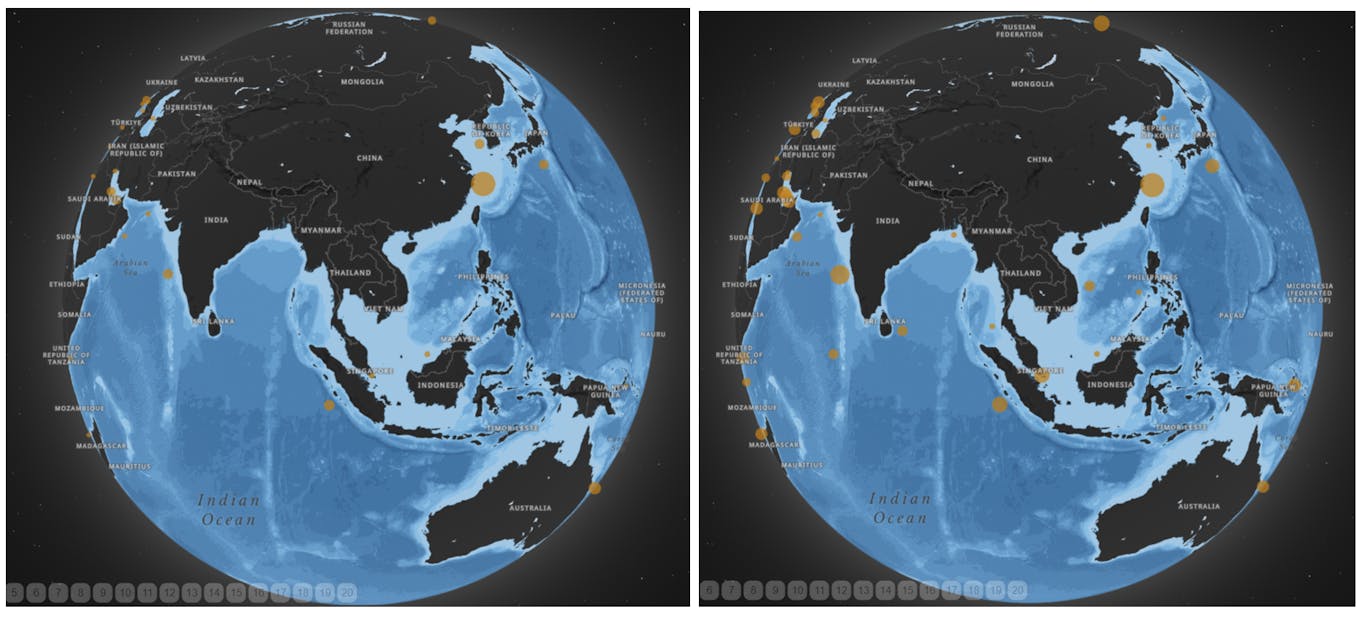

Based on the analysis of data between 2012 and 2019, the extraction rate of sand and other sediments – estimated by the Marine Sand Watch to be between four and eight billion tonnes – is approaching the natural replenishment rate of 10 to 16 billion tonnes per year needed to maintain coastal and marine ecosystem function.

This is especially concerning for Asia, where most of the world’s sand is being extracted. For instance, sand mining in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta – built up by 6,000 years of silt deposits – has led to sinking land and coastal erosion.

Despite the intensity of dredging in Southeast Asia, the platform is currently unable to track mining activity in the region, as many countries do not require dredging vessels to emit Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals, said Arnaud Vander Velpen, sand industry and data analytics officer, Global Resource Information Database (GRID-Geneva), the centre for analytics for UNEP at the press conference.

These signals are used to identify a ship’s real time position and to map out mining in sand concessions, offloading locations, maintenance dredging and other types of activities like land reclamation on the platform.

Given that artisanal and small-scale mining along very shallow coastlines is done with small boats that do not transmit AIS, Vander Velpen added that Marine Sand Watch will need to use other types of technologies, like remote sensing drones and lifecycle analysis to detect the amount of sand being used.

Estimated sand dredging activities, represented by orange circles, in the exclusive economic zones of countries in Asia Pacific in 2012 (left), compared to 2019 (right). The bigger the circle, the larger the volume of sediment extracted. Image: Marine Sand Watch

“The scale of environmental impacts of shallow sea mining activities and dredging is alarming, including biodiversity, water turbidity, and noise impacts on marine mammals,” said Pascal Peduzzi, director of GRID-Geneva, which developed the platform with support from the University of Geneva, the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment and the German Federal Ministry for the Environment.

“This data signals the urgent need for better management of marine sand resources and to reduce the impacts of shallow sea mining,” added Peduzzi. “UNEP invites all stakeholders, member states and the dredging sector to consider sand as a strategic material, and to swiftly engage in talks on how to improve dredging standards around the world.”

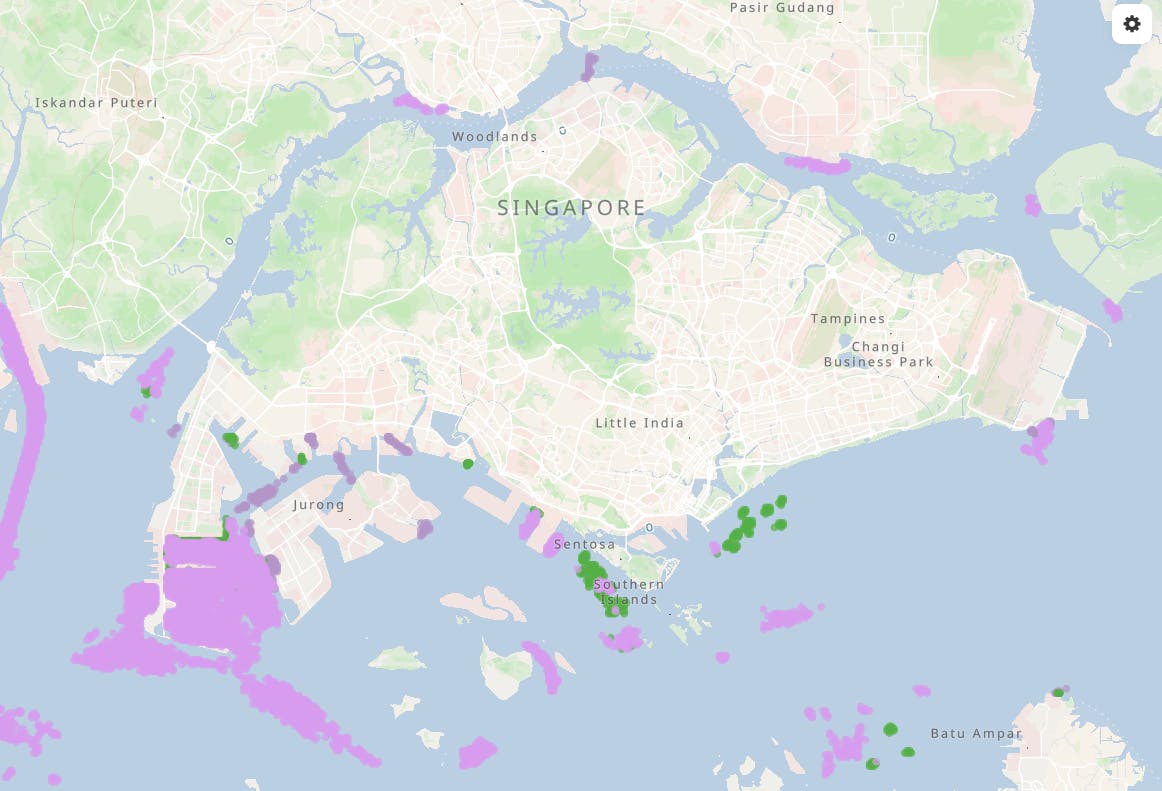

Asia is home to the largest consumers of the world’s most-exploited resource after water for construction and land reclamation. China – which helped to build Sri Lanka’s Colombo Port City on reclaimed land, an effort that required about 65 million cubic metres of sand – alone accounts for the use of half of the world’s sand for building its infrastructure, Peduzzi told Eco-Business. According to data from the Singapore Land Authority, Singapore has also increased its land area by more than 25 per cent since the 1970s using sand imported from neighbouring countries.

Identified dredging activity up until 2019 near Singapore by trailing suction hopper dredgers (in pink), which are involved in all types of dredging activities, and cutter suction dredgers (in green), which are mainly used in land creation and deepening of new waterways. Image: Marine Sand Watch

In its report last year, UNEP called for better monitoring of sand extraction and use, the ban of sand extraction near beaches and an international standard on sand extraction.

Following the launch of Marine Sand Watch, GRID-Geneva will be attending a global consultation with member states around the UN Environment Assembly’s resolution to strengthen scientific, technical and policy knowledge on sand, among other minerals and metals that are widely extracted.

“I assume that a lot of countries are interested [in the tool] because it is their resources, they need to manage it for the long term,” said Peduzzi. “We also want to use this to initiate discussion with the dredging industry.”

While countries like Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam have banned marine sand exports in the last two decades, others lack any legislation or effective monitoring programmes thus far. However, it remains unclear how effective national policies are to deter unsustainable sand extraction and use.

Earlier this year, Indonesia lifted its 2003 ban on exporting sand dredged from the sea, a move that was criticised by environmental activists and marine experts for serving business interests at the expense of marine ecosystems and fishing communities. Before the ban, the archipelago was a major supplier of sea sand to Singapore for land reclamation, shipping over 150 million tonnes between 1997 and 2002.

Extraction of this globally demanded commodity drives biodiversity loss and exposes coastal communities to rising sea levels and storms. Shallow sea mining for sand and gravel, also referred to as marine sand, exacerbates flood risk by removing natural barriers to storm surge and undermines support for biodiversity, fisheries and other blue economy activities.

Apart from being used in construction and land reclamation, marine sand is also used to deepen waterways and build harbours, replenish beaches, build coastal defenses and support offshore energy infrastructure like wind and sand turbines.

“Nobody knew how much sand was taken out of the oceans and we want to answer that question through this platform,” said Peduzzi.

The platform currently monitors large vessels dredging sand, clay, silt, gravel and rock in the world’s marine environment, including hotspots like the North Sea, Southeast Asia, and the East Coast of the United States, up until 2019. Peduzzi said that Marine Sand Watch aims to improve its algorithms to calculate how much sand is being extracted as “not all sediments are sand”.

A zoomed in satellite image of an offloading site near Schiedam in the Netherlands. Image: Marine Sand Watch

In the next few months, the platform will also be adding additional data all the way up to 2023, said Vander Velpen. In the meantime, there are plans to develop an updated version to move towards near real-time monitoring which will also be able to fully detect all existing dredging vessels, as well as to better differentiate between the types of vessels and dredging activities.