In its first ruling on trade matters related to deforestation and carbon emissions, the World Trade Organisation found fault with the way the European Union decided against accepting palm oil as a source of renewable energy.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Although the international trade governance body agreed that it was valid for the EU to establish rules against crop-based fuels like palm oil due to the deforestation and emissions risks of indirect land use change (ILUC), it argued that the bloc had developed and implemented these rules in a way that constituted “arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination” against trading partner Malaysia.

“There are deficiencies in the design and implementation of the low ILUC-risk criteria,” the WTO panel said in a complex, 348-page report published last Tuesday.

The panel ruled on multiple complaints brought against the EU, France and Lithuania by Malaysia beginning in 2021. Malaysia, the world’s second largest producer of palm oil after Indonesia, argued that the EU had violated international trade rules when it decided on a cap and phase-out designed to limit the use of palm oil as a biofuel under the bloc’s second version of its Renewable Energy Directive (RED II). Indonesia had filed a similar case against the EU in 2019 but asked for the proceedings to be suspended last Monday, a day before the result of Malaysia’s case was announced.

Among Malaysia’s key contentions was the EU’s use of a 10-year limit to determine which crops can be certified as having low ILUC-risk. While the timeframe makes sense for crops that are harvested and replanted such as rapeseed or sunflower seed oil, it would rule out the certification of palm oil as low-risk as oil palm trees only begin to fruit at 7 or 8 years old but typically have a 25 to 30-year lifespan, said Khalid Manaf Hegarty, an international trade policy expert and director of Australia-based consultancy Oxley Hegarty.

“Going through the panel report, the WTO actually asked the EU why they [set that time frame], but the EU didn’t have an answer for that. It was arbitrary,” Hegarty told Eco-Business. If the EU was being genuine about reducing emissions via their life cycle impact assessment, he said, they could find ways to consider crops that might have better emissions reduction capabilities over a 25-year period compared to annual crops.

The WTO panel also criticised the review period of the data used by the EU in assessing the ILUC risk of palm oil, which was based on data gathered between 2008 and 2016. This meant that the EU’s high ILUC-risk cap and phase-out relied on potentially outdated data.

Following the ruling, the EU’s Directorate-General for Trade said that the bloc “intends to take the necessary steps to adjust the Delegated Act” under RED II, which established the criteria used to determine which food and feed crop-based biofuels have high ILUC-risk.

Malaysia’s minister of plantation and commodities Johari bin Abdul Ghani responded saying that his ministry would “closely monitor the EU’s changes to its regulations to bring it in line with the WTO’s findings, and pursue compliance proceedings if necessary.

“This ruling from the WTO demonstrates that Malaysia’s claims of discrimination are indeed justified. This vindicates Malaysia’s pursuit of justice for our biodiesel traders, companies and employees,” Johari said in a press statement.

One dissenting member on the WTO’s three-person panel vindicated Malaysia’s argument further, giving more weight than the other panellists to elements of protectionism by the EU in establishing trade rules. The EU appeared to have singled out palm oil when it came to limiting ILUC-related emissions, even though other types of crop-based biofuel feedstocks such as soybean seemed to pose similar emission risks, the panellist said.

Deforestation-related backlash

The WTO’s ruling comes amid wider backlash against the EU for deforestation-related rules. On Friday, the Financial Times reported that the EU could delay its classification system for trading partners at risk of deforestation. The report cited an EU official who said the bloc had received a lot of complaints from partners.

Indonesia and Malaysia are among the countries which have long accused the EU of discrimination against palm oil and other commodities under the European Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). Indonesia argued to the WTO that is has taken effective action to prevent deforestation and mitigate climate change over the past decade. Last year, reports showed that the country has achieved record declines in deforestation rates.

“Indonesia [in its WTO case against the EU] outlines clear outcomes and policy shifts on sustainable development, and we hear it has (sic) a specialist team that brought substantial new data to its discussion,” said Khor Yu Leng, director at Segi Enam Advisors, a market research and intelligence consultancy whose coverage includes the palm oil industry.

Khor said she would be keeping an eye on subsequent developments in Indonesia’s case against the EU at the WTO after the case brought by Malaysia concluded with “no clear decision on market access.”

Palm oil is currently the first choice of biodiesel blends in Malaysia and Indonesia, both of which have mandates that require the use of a biofuel blend with fossil fuel sources. Indonesia currently requires a blend of 35 per cent biofuels in its diesel mix (B35) and is aiming to raise this to 40 per cent, or B40 by 2030. Meanwhile, Malaysia only requires a 10 per cent blend of palm oil for its transportation sector (B10).

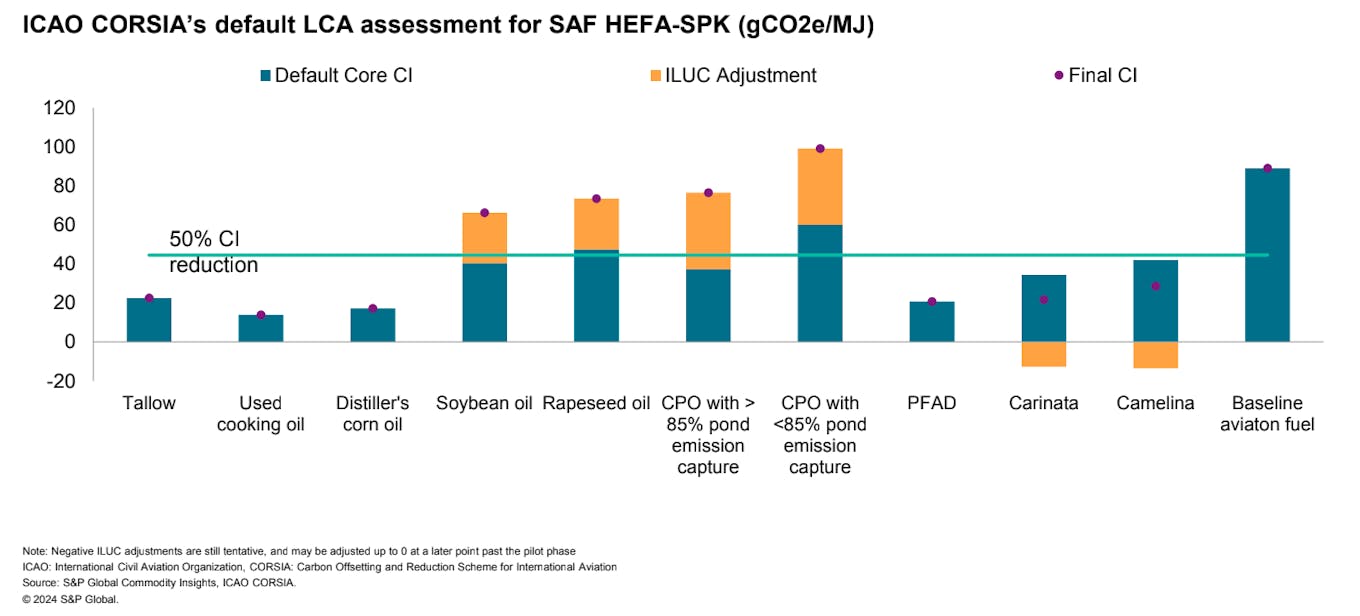

The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) has assessed the carbon intensity of various biofuel feedstocks, adjusting for the indirect land use change (ILUC) risks of palm oil and other agricultural crops. Image: S&P Global Commodity Insights

Because biofuels are currently more expensive than fossil fuels, official mandates are necessary to drive demand in this energy source, said Ji Yang Lum, senior principal research analyst for biofuels at S&P Global, a financial information firm.

“What we’ve seen over the past five years are evolutions to these mandates,” he said at an industry conference in Kuala Lumpur last Tuesday. The EU, for example, has prioritised meeting decarbonisation targets without impacting the food market, which explains why they’ve chosen to phase out food and feed crops as feedstocks, he added.

For palm oil-based biofuels, S&P Global sees limited growth in the road transportation fuel sector, given the current limited mandates for biodiesel in Malaysia and Indonesia. Industry players are therefore exploring the use of palm oil in sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), said Lum, which is currently allowed by the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) under its global carbon offsetting programme Corsia.

Increasingly, the carbon footprint of different biofuel feedstocks will also matter. “Carbon intensity matters when looking at biofuels (because) we are seeing a push towards counting the carbon intensity of your feedstocks rather than just using a biofuel,” said Lum.

The ICAO’s life cycle assessment of different biofuel feedstocks currently sees palm oil as having high ILUC-related emissions (see graph) but Lum believes there is room for palm oil to “bridge the gap” that currently exists in SAF due to the limited supply of lower-intensity feedstocks.

With respect to deforestation, however, biodiesel mandates will matter less than government policies on land and forest management, said Hegarty.

“If your land use planning and land management laws are good enough, it isn’t going to matter whether you’ve got the biofuel policy in place or not,” he said.