Recognising the problem of overfishing, the 164 member countries of the World Trade Organization (WTO) have been trying for more than two decades to reach an agreement on eliminating harmful fishing subsidies.

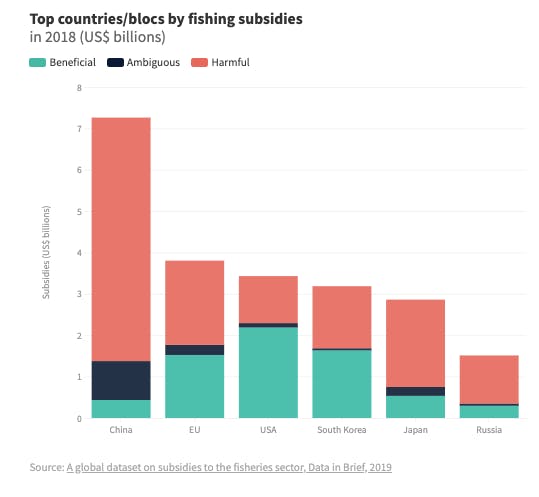

Of the US$35 billion of public subsidies that went into supporting global fisheries in 2018, $22 billion were classed as harmful because they increased fishing capacity, largely through fuel tax exemptions.

The deadline for agreeing a deal to end such subsidies, in accordance with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is this year. But meeting it will be highly difficult, experts agree.

The WTO has already cancelled its Ministerial Conference, scheduled for June in Kazakhstan, and negotiations are now on hold until measures to curb the pandemic are further lifted.

Keith Rockwell, WTO spokesperson, said the ability of many Geneva-based delegations to liaise with their home nations and other delegations has been “restricted” due to the outbreak – which has now become the priority for them over other WTO-related matters.

Ambassador Santiago Wills of Colombia, who leads the fisheries subsidies talks at the WTO, has not yet presented a consolidated draft of the agreement. He has tried to maintain talks online, but that has proven difficult for several national delegations, slowing progress.

In a recent webinar hosted by NGO Chatham House, Wills said he was still hopeful of a deal this year but that there are “still many issues to resolve”. Though coordination between delegates “has been difficult” due to the pandemic, he confirmed that the commitment of all delegations to reaching an agreement remains strong.

Isabel Jarrett, manager of the Pew Charitable Trusts programme to reduce harmful fishing subsidies, said: “Members have to get down to drafting the text. But as negotiations can’t take place in person and virtual negotiations are difficult we don’t have a clear sense of timeline for the rest of the negotiations.”

Remaining challenges

For Enrique Sanjurjo, senior ocean manager at WWF Mexico, countries had been making progress in the negotiations before the coronavirus outbreak. Now the situation looks bleak and he dismisses the possibility of a deal this year.

“Countries have come to an understanding on some areas. For example, they now agree illegal fishing shouldn’t be subsidised, as well as fishing of overexploited species,” he said. “But there’s disagreement over definitions, such as what actually is illegal fishing or an overexploited species.”

Further differences remain over the impact that eliminating subsidies would have on artisanal, or small-scale, fishers in developing countries. They rely on pay-outs and exceptions, which is why India and other nations have been strongly pushing for special and differentiated treatment.

Remi Parmentier, director of environmental consultancy the Varda Group, added another complication to the list. In the midst of the pandemic, countries have been providing aid packages or subsidies to the fishing industry. For example, the US set aside US$300 million of its US$2.2 trillion stimulus bill just for fisheries.

“There’s a wide debate now regarding what the aid packages of the Covid-19 crisis should contain. The discussion on fishing subsidies is part of that. It’s an opportunity to change mindsets and paradigms,” he said. “Many say we shouldn’t support fossil fuel subsidies and the same can be said with fisheries.”

All proposals from countries now on the table include the prohibition of subsidies linked to unreported and unregulated fishing and to the exploitation of already overfished stocks. Nevertheless, they vary on the methods of implementation and reform limits.

China, which operates the world’s-largest fishing fleet, pitched a proposal last year to cap and reduce subsidies over time. Jarrett said that while the country has been “quiet” at the negotiations, the fact that it filed a proposal shows its “willingness,” highlighting the changes already made to subsidies for its domestic fleet.

The WTO rules require decisions to be made by consensus. For Jarrett, we aren’t there yet. “We need high-level political engagement of all decision-makers as that can help shift some positions,” she said.

The European Union, Japan, China, the United States and Russia spend the most on fishing subsidies.

As a result of the expansion of industrial fishing fleets over time, 90 per cent of fish populations are fully exploited, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

“If we don’t set aside our differences in these negotiations, the boats will go out one day to find that there are no longer any fish over which to argue. Actually, that has already happened in some places and continues to happen today,” added Rockwell.

This story originally published by Chinadialogue under a Creative Commons’ License.