One of the most valuable commodities in the global marketplace, coffee travels a complicated journey from crop to cup.

After the beans are farmed and harvested by growers across Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America, they typically go through several stages before the final brew, often changing hands a few times before landing in a cup hundreds of miles from their point of origin.

The fragmented nature of the industry is one of the biggest challenges to sustainability in coffee supply chains, says Juan Antonio Rivas, senior vice-president of coffee sustainability at food and agribusiness firm Olam International.

“There are many coffee-producing countries and in each of those countries, a very large number of farmers. These are mostly smallholders managing only one or two hectares of land, with many intermediaries, including exporters and roasters, making up the rest of the value chain,” he said. “The coffee industry has become very commoditised because of this, and prices very volatile.”

Threats to the future of coffee

Coffee farmers often find themselves at the wrong end of the value chain, receiving only a tiny fraction of the sale price of coffee at supermarkets and global coffee chains. Even as coffee consumption is growing worldwide, farmers are sometimes unable to cover their production costs.

“It’s extremely difficult for a coffee farmer to make ends meet, even when coffee prices are high,” said Rivas, who added that smallholder farmers who lack access to education and technology are particularly disadvantaged.

For instance, most farmers are not able to afford processing equipment to prepare coffee beans for export and roasting, often relying on contractors or exporters, who get a bigger cut of the product’s end-price.

Furthermore, when farmers have trouble making a living from their crop, it makes it harder for them to consider the environmental impacts of their agricultural practices and farm more sustainably.

“When the farmer is struggling to make ends meet, it’s much harder to have a conversation on how they should be treating the water in a certain way or how they should take care of the environment,” said Rivas.

“

Agricultural supply chains, particularly coffee, are immensely complex. If you are a consumer looking to connect what you consume to the farmer… it’s extremely difficult to see unless there is a one-stop source where measurable data can be collected and visually presented to coffee buyers worldwide.

Roel Van Poppel, chief executive officer, AtSource

The average water footprint of a 125-millilitre cup of coffee is 132 litres, according to the Water Footprint Network. Untreated waste from wet coffee mills can also pollute the water in surrounding streams and rivers, affecting the drinkable water of communities in the area.

“Each country has different issues, which makes it hard to come up with a one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to sustainability. Coffee farmers in Vietnam, for example, are technologically adept, but typically use a lot of fertiliser, which is bad for the soil,” said Rivas. “In Colombia, on the other hand, the main focus for Olam is building climate resilience for farmers and coffee.”

Colombia is one of the biggest coffee-producing nations in the world alongside Vietnam and Brazil, but its fertile mountains are already facing extreme weather threats such as flooding and drought, as well as the spread of invasive pests.

A 2019 report by scientists at Britain’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew revealed that 60 per cent of wild coffee species could be gone in the next few decades due to climate change and, by 2050, the land suitable for growing Arabica, the oldest variety of coffee, might be slashed by half.

Improving transparency in the coffee chain

As awareness of sustainability and ethical consumerism grow, there is pressure on the industry to reduce the environmental footprint of coffee, pay coffee farmers a fair wage and ensure that their livelihoods are not compromised by climate change and other direct threats to health, safety and food security.

“Companies all over the world are thinking of how they can increase sustainable production and develop more transparent supply chains. Millennials and Generation Z are especially demanding action, so companies are thinking of how to demonstrate transparency and be more action-focused in the areas where they can make a difference,” said Roel Van Poppel, chief executive officer of AtSource, a digital traceability tool and business-to-business sustainable sourcing platform launched by Olam in 2018 to increase transparency across its product supply chains.

Coffee from Brazil and Vietnam was among the first five supply chains introduced on AtSource, which has since been rolled out to 11 products across 35 origins and 70,000 farmers. They include rice from Thailand, cashew from Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana, quinoa from Peru, onion from the US and Egypt, and coffee from an additional 15 origins.

“Agricultural supply chains, particularly coffee, are immensely complex. If you are a consumer looking to connect to what you consume to the farmer that is producing the ingredients that goes into your cup of coffee, it’s extremely difficult to see unless there is a one-stop source where measurable data can be collected and visually presented to coffee buyers worldwide,” Van Poppel added.

The data collated through AtSource allows Olam’s coffee buyers to be more transparent with their own customers. “Through our action-focused work on the ground and the data we are gathering, we build narratives for our customers, who can now tell coffee consumers exactly what improvements they are helping to make in their supply chain,” he said.

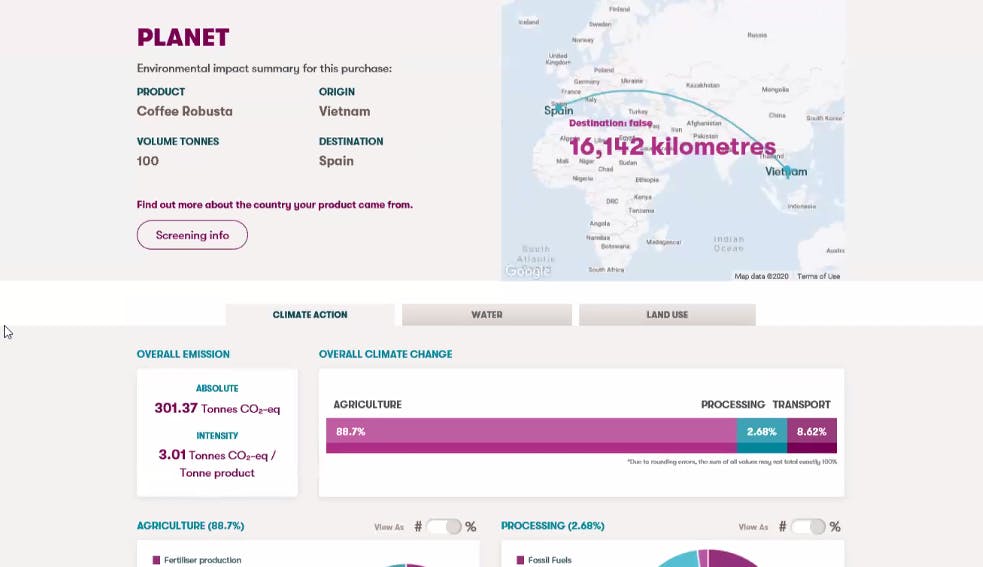

Olam’s online traceability tool AtSource allows its coffee customers to track the social and environmental impacts of their coffee products. Image: Olam International

Through AtSource’s online dashboard, a buyer supplying a café in Germany can find out how the coffee it sources from Brazil is affecting water and land use, and can even calculate the emissions from the entire production process and its impact on climate change.

Olam’s customers can also look at how farms are faring on social metrics such as gender diversity, access to education and food security. A few of AtSource’s metrics that contribute to increasing farmers’ incomes include the number of farmers receiving agronomy training, bonus payments, the total value of farm support equipment and the beneficiaries of farm inputs such as fertiliser and seeds.

The data has been promising. At coffee farms in Daklak, Vietnam, farmers’ production costs were reduced by 32 per cent in 2019 because of lower input costs from better application of fertiliser and water resources. Currently, 1,400 coffee farmers in Vietnam are part of the company’s programme to improve sustainability and transparency in the coffee production process.

“AtSource has given us a lot of direction in understanding what we want to measure and what kind of progress we want to see through different indicators. We decided on the things we wanted to measure and tried to create a consistency where everyone can track the same metrics,” Rivas said. “Coffee is such a decentralised industry so this goes a long way towards raising the standard that buyers can work towards.”