Asia’s water resources face a triple threat — climate change leading to extreme floods and droughts, clustering of cities around the major river basins, and coastal threats.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Although the water risks are huge, the energy transition continues to dominate discussions about climate risks.

“If you properly value the risks, water risks would be much greater than the energy transition risks,” said Debra Tan head of China Water Risk, on a panel at Singapore International Water Week 2021.

Speaking on a panel titled Sustainability Leadership in Water: Experiences from Industry and Utility, she said that properly assessing the complexities around water risks would see a fast-tracking of decarbonisation and a rise in climate adaptation.

“

“We have the technology and the know-how to deliver water solutions, but do we have the political will to do so?”

Debra Tan, head, China Water Risk

Cecilia Tortajada, senior research fellow, Institute of Water Policy, National University of Singapore agreed. She said: “When we see discussions in the international arena regarding climate change, water is not considered. One of the ways in which climate change is tangible in our lives is through floods and droughts, but even then, water is second, third or even fourth priority. Yes, carbon is important, but water is important too.”

One in two Asians live in just 10 river basins, which collectively drive over US$ 4 trillion of GDP. With over 280 cities clustered around these rivers, and more people flocking to the cities, the river flow will only be more valuable moving forward.

“Countries cannot allow these rivers to fail, and need to start looking at them as assets,” said Tan.

In addition, cities in Asia Pacific are particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise. A recent report that benchmarked 20 coastal capitals in the region found that urban real estate equivalent to 59 Singapores will be underwater without serious adaptation measures if we continue business-as-usual. Cities like Taipei, Macau, Tokyo and Hong Kong were in the bottom quartile.

“Rising seas also have salt water intrusion implications for fresh water. The whole system needs to be looked at together, from mountains to oceans,” Tan added.

“We have the technology and the know-how to deliver solutions, but do we have the political will to do so?” Tan asked.

Triangle of trade-offs

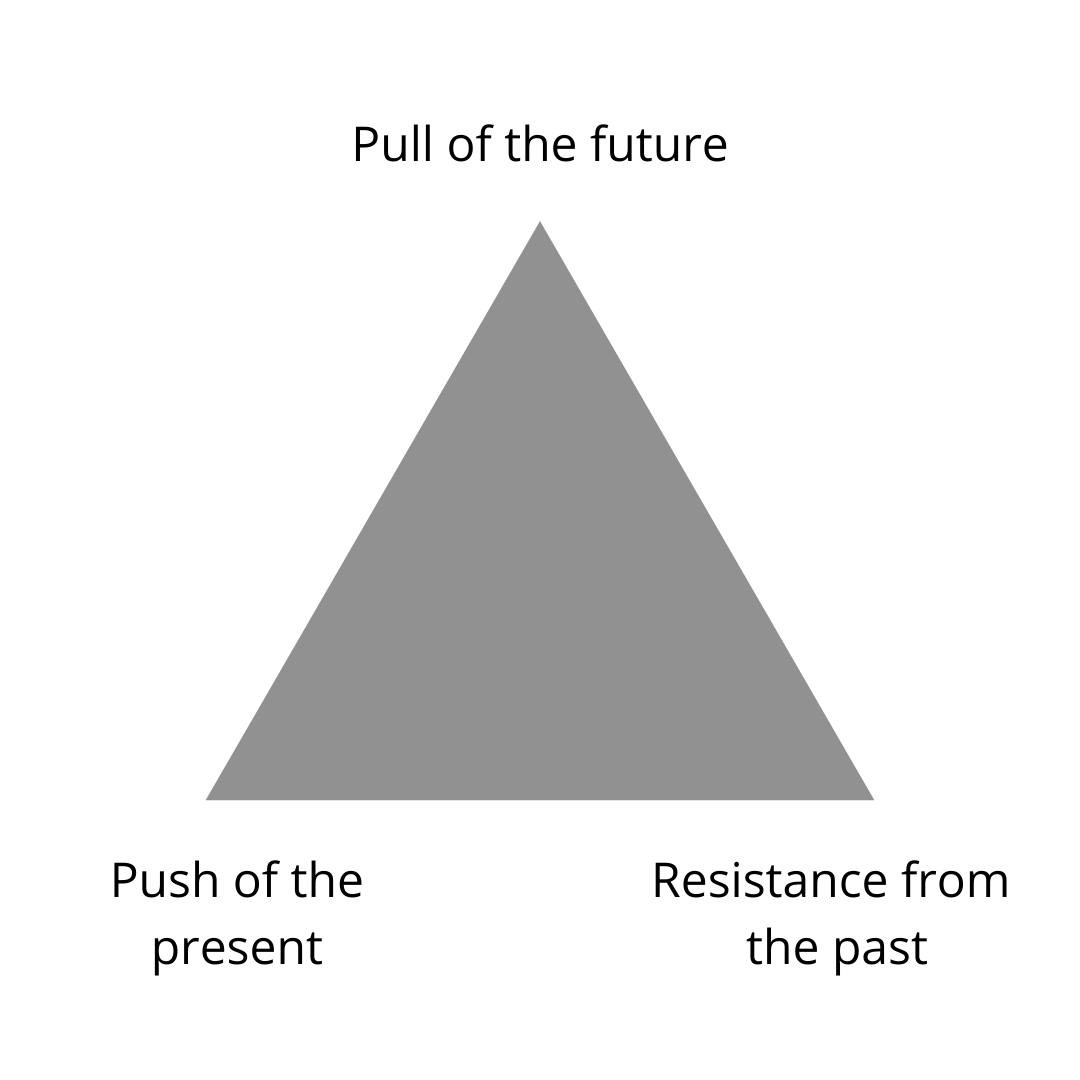

Philippe Rohner, co-founder and managing partner of Abic Partners brought a timeframe into the discussion surrounding water, with what he called the ‘triangle of trade-offs’.

The triangle of trade-offs, representing the pull of the future, the push of the present, and the resistance from the past. Image: Eco-Business

“On the bottom left of the triangle, we have the push of the present, which are the current risks and trends,” he explained.

On top of environmental risks, there are other factors to consider, such as the rise of urbanisation, demographic shifts, and the behaviour of consumers that impact what industry does, he added.

At the top of the triangle lies the pull of the future, the aspirations we have as a society, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), he said. SDG 6 seeks to ensure safe drinking water and sanitation for all, focusing on the sustainable management of water resources, wastewater and ecosystems.

Lastly, the bottom right of the triangle represents the resistance from the past—embedded infrastructure, the way civil society and corporates organise, and economic regulations.

“These three forces and timescales are what determine the impact and uncertainties we face when thinking about the future of water resources,” Rohner said.

Covid-19 has increased the gap between these forces as millions of people have been thrown back into poverty, increasing the gaps between willingness to pay and the ability to pay, he said. In addition, the pandemic has highlighted water risks and the importance of water in ensuring sanitation and health.

The true value of water

The first step to protecting water resources would be to introduce the price of raw water—water found in the environment that has not been treated, such as rainwater, ground water, and water from lakes and rivers—to develop technologies and good policies. Doing so would also ensure that more funding is allocated for various water projects.

“When people consider raw water to have no value, it’s difficult to develop technology for reusing water or for the artificial charing of groundwater, because you’re comparing something which is quite expensive to something which is considered free,” said Diane D’arras, immediate past president of International Water Association.

It’s important to develop the value of raw water, and find a business model that ensures people are sharing it, she added.

“It’s similar to the concept of carbon emissions — if we want to reduce carbon emissions, we need to introduce the notion that there’s a cost for generating it,” she said.

In the region, China has set an example of tying water use targets to economic activity, said Tan. Since 2011, the country has set national protocols, water efficiency and pollution targets that are tied to its GDP.

By allocating water nationally, provincially, by sector and by basin, the country has managed to increased the standards of compliance and push technology and innovation across multiple sectors, she added.

Non-technological innovations

While technological innovations such as desalination plants are important, they can’t solve everything, warned D’arras. Before pushing out new technologies, having a global policy to reduce water use is most important.

“Many new and green technologies may not entirely be clean. There are social issues with the minerals needed for these new technologies and we need to be mindful that in creating a greener world, we don’t end up polluting water resources,” Tan agreed.

“Before we go all guns blazing into new green technologies, we need to be mindful that the environmental compliance and regulations are more relaxed in many of the countries where these materials are mined,” she added.

Policy innovation, longer-term financing and behavioural nudges are some non-technological innovations that are needed, the experts said.

“I would like to see the rise of more water-focused policies. Fundamentally, water is a cross-cutting issue and government structures aren’t prepared to cope with this yet. We need to restructure some agencies and manage water resources in a holistic way,” said Tan.

“If water is truly valuable, it has to be recognised by everybody—industry, the government and end users,” she added.