One in nine people around the world are hungry—a total of 821 million people worldwide. But global food security is actually improving, with over 70 per cent of countries strengthening their scores in this year’s Global Food Security Index (GFSI).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

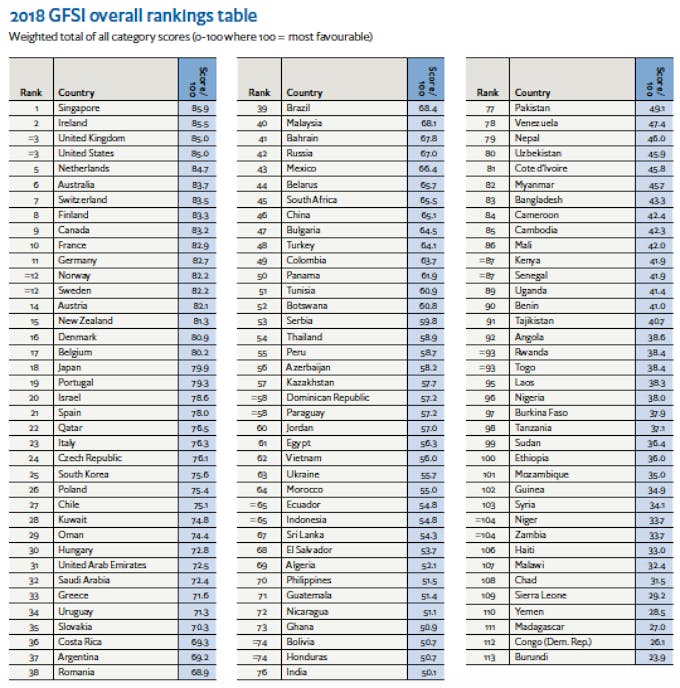

But only two countries from Asia-Pacific feature in the index’s top 10, with Singapore topping the list for the first time and Australia ranking sixth. At the bottom of the rankings, Laos, Cambodia, Bangladesh and Myanmar are positioned among the world’s least food-secure countries, most of which are in Africa.

Overall rankings in the Global Food Security Index. Source: Economist Intelligence Unit

Released by the Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU), the index measures how affordable, available, safe and up-to-standard food is across 113 countries.

Risks to Asia’s food security

There’s “work to be done” to improve the region’s food security, particularly in Southeast Asia and South Asia, according to Gustavo Palerosi Carneiro, head of chemicals firm BASF’s agricultural solutions business in Asia-Pacific.

“Overall, farmers in Asia produce less food per hectare than other regions. For rice, only Korea exceeds the OECD average yield. No country in Asia exceeds the OECD average for other staple crops like soy and corn,” he told Eco-Business.

Trade barriers, such as import tariffs, also affect food security. “Countries like Sri Lanka, Thailand, India and South Korea have higher tariffs than other indexed countries,” commented Robert Smith, a consultant at EIU. India’s food subsidies endanger their own food market by limiting foreign investments, Smith said.

Farming practices and food production in Asia-Pacific are likely to be impacted by a variety of climate risks: increasing temperature, drought, fire and rising sea levels—affecting growth and often destroying crops, according to Smith.

“

While there may be safety and sustainability concerns, the reality is that it will be impossible to meet future demand without genetically modified food.

Gustavo Palerosi Carneiro, senior vice president, agricultural solutions, Asia Pacific, BASF

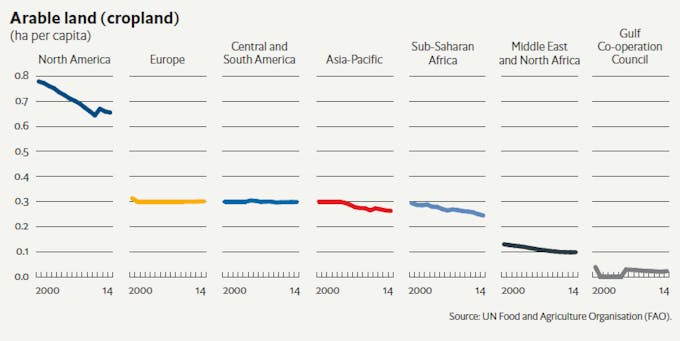

According to the report, Asia-Pacific’s arable land has decreased over the past decade. Source: UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO)/Economist Intelligence Unit

Asia’s farmers are among the most vulnerable to climate change. “Rising sea levels threaten productive coastal areas and river deltas with increasing levels of salinity. New solutions, such as crops bred to be drought-resistant and salinity-resistant need to be developed and deployed,” Carneiro said.

Rising sea levels and drought is hurting Southeast Asia’s Mekong River Delta, which produces over half of Vietnam’s food. Agriculture in Cambodia, Laos and Thailand are affected by storms, excessive rain and extreme heat. Archipelagos such as Indonesia and Philippines, with their long coastlines, are similarly vulnerable; the Philippines is hit by, on average, 20 typhoons a year.

How to make Asia more food secure

Agricultural technologies, such as genetically-modified (GM) crops, are important tools that farmers will need to increase yield, Carneiro suggested.

“While there may be safety and sustainability concerns, the reality is that it will be impossible to meet the future demand for food without it,” he said. “It is critical to use these technologies safely and responsibly, ensuring the safety of farmers, consumers and the environment.”

“There is extraordinary pressure on Asia-Pacific farmers to boost agricultural productivity, given the region’s forecasted growth. As the middle-class booms, demand for nutritious and healthy food is surging—requiring more sophisticated farming practices,” Carneiro said.

The use of digital farming tools will help growers to use crop protection solutions more effectively by combining data with artificial intelligence, he added.

Improving agricultural infrastructure is crucial to reduce food loss in the supply chain, as are governmental efforts to finance farmers through insurance and agricultural credit, Smith noted.

Carneiro agreed. “To boost agricultural yields in Asia, we need to look at the limiting factors—including the prevalence of small, fragmented farm holdings, lower technology use, and water shortages. Fortunately, we have seen interest from governments and farmers to help bridge the gaps through investment in land reform and infrastructure.”

Asian countries can also improve their food security scores by developing national dietary guidelines, promoting healthy eating and increasing access to potable water, Smith added.

Lessons from a tiny island

Singapore, a small island with limited natural resources and barely any agriculture, claimed first position in the food security index due to its strong economy and open trade environment.

Yet Singapore is highly import-dependent, and therefore susceptible to trade disruptions as food-producing countries may reduce exports to ensure their own food security. “Therein lies the paradox—Singapore is threatened by changes in food trade, as well as climate and natural resource risks,” Smith said.

Singapore has the lowest food import taxes of the 113 countries in the index, so the impact of varying international food prices increase is considerably softened, the report found.

Singapore scored less than the next 20 countries in the index for food quality and safety. According to Smith, this is partially due to the high consumption of rice and the absence of certain essential amino acids in the diet.

Even so, Singapore has strong structural policies in place for food quality and safety, and is introducing a new government agency dedicated to food security and safety—the Singapore Food Agency, which is launching next year.