The world is falling short on investments in technology for climate adaptation because of a lack of metrics that can measure clear financial returns or help investors quantify the impact these investments have on affected communities, said World Bank executives at a climate finance conference on Tuesday in Bilbao, Spain.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Adaptation technology, which includes early warning systems, defenses against sea level rise or innovations that prepare communities for extreme heat or essentially reduce the risks they face from climate hazards can be seen by investors as costly if they cannot foresee the net benefits of their investments, said Hania Dawood, practice manager, climate finance and economics of the World Bank.

“It is difficult to design financial instruments that [allow for] upfront funding of climate adaptation,” Dawood said at a media briefing at the summit, which brought together public and private sector players to discuss how to accelerate the push for innovative climate solutions. Outcomes cannot be clearly defined, unlike that for investments in mitigation efforts, where emissions reductions can be measured, she added.

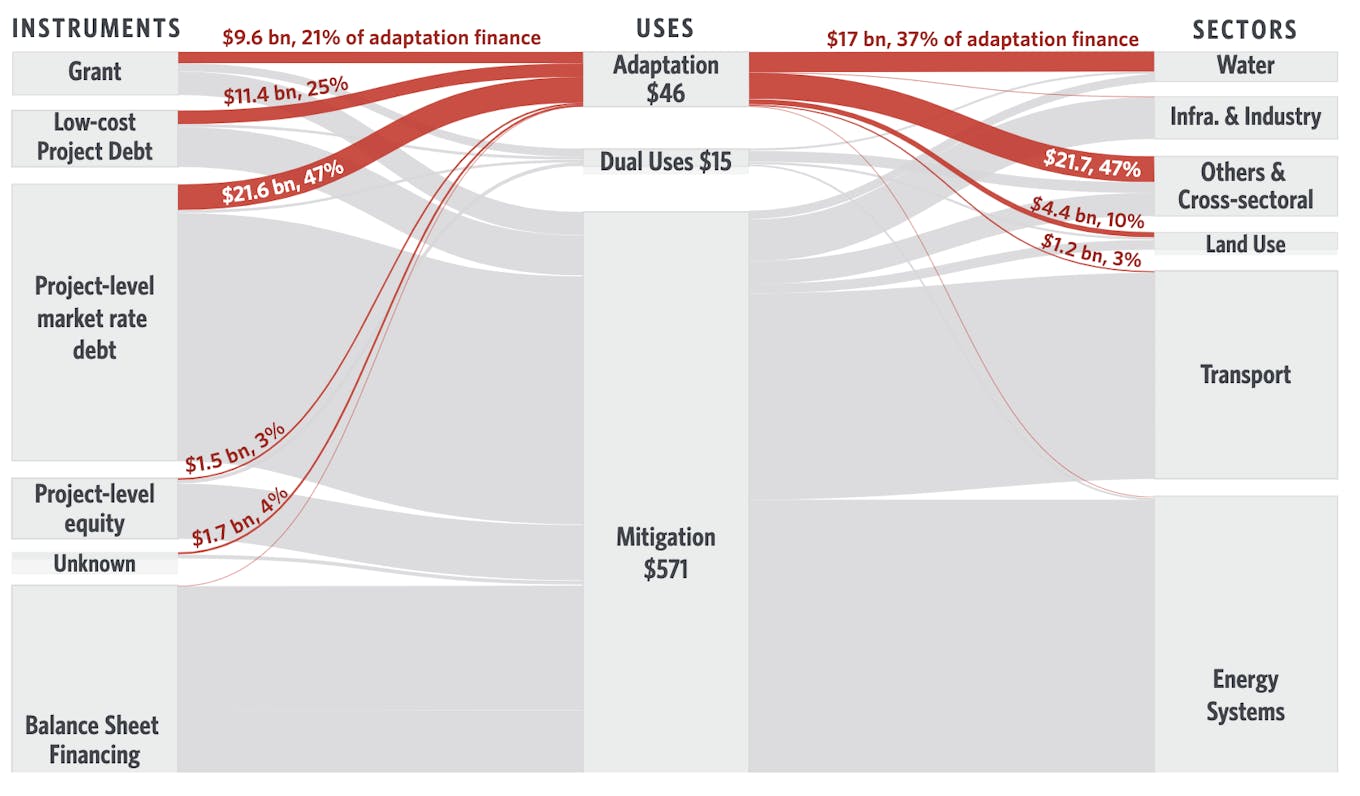

Dawood cited how finance for climate adaptation reached US$46 billion in 2020, a figure that lags about twelve times behind what was spent on mitigation which includes funding for renewable energy sources. This is according to latest data from United States-based non-profit research group Climate Policy Initiative.

The same study had found that only about 12 per cent of climate adaptation finance has come from corporations and institutional investors, with multilateral development banks and governments footing most of the bill.

Finance for adaptation increased to US$46 billion in 2020, a 53 per cent increase from US$30 billion in 2018.. Despite this positive trend, Total adaptation finance, however, remains far below the scale necessary to respond to existing and future climate change. Image: Climate Policy Initiative

Karan Mangotra, senior climate change specialist for South Asia of the World Bank, said investors are more keen on pouring money into renewables because the impact from these investments are more visible and measurable.

There is “common understanding” among public, private and multilateral financiers on how a shift to renewables can help curb carbon emissions, create jobs and safeguard biodiversity, and there are proper and more standardised metrics to measure these impacts, Mangotra told Eco-Business at the sidelines of the summit. This is not the case now for climate adaptation technology, he added.

This is especially as impacts of adaptation technology, when applied in different locales, vary. In short, adaptation is context-specific.

For instance, Mangotra cited how the approach to disasters in the east coast of India is different from what happens in the west side as local metrics are not comparable.

Mangotra points out that when the renewables sector was first emerging, it had faced the same issues of funding. “Then, the private sector was not accustomed to changing parameters too…Data was hard to quantify. [Investing in] adaptation today, for investors, is what doing so for solar technology was like a decade ago,” he said.

Karan Mangotra (far right), senior climate change specialist at the World Bank, speaks at a panel on how disaster risk reduction investments drive climate adaptation as part of the Innovate4Climate conference in Bilbao, Spain. Image: World Bank

Funding for “loss and damage”, a concept closely related to adaptation finance and which helps communities deal with the costs associated with climate impacts, has been an emerging point of contention in climate negotiation in recent years.

At the COP27 climate summit last year, a breakthrough agreement on setting up such a fund to provide financial assistance to nations most vulnerable and impacted by the effects of climate change was achieved. Governments are working out a precise scope on how and how much of such financing can be disbursed.

Ahead of the climate summit in 2022, the United Nations also released a report that found how international adaptation finance flows to developing countries were up to 10 times below estimated needs. This prompted United Nations chief António Guterres to call for doubling support for adaption to US$40 billion annually by 2025.

Meanwhile, funding for climate mitigation which includes solar and onshore wind continue to be the main recipient of renewable energy finance, attracting over 91 per cent of all mitigation investment. Multilateral development banks have continuously emphasised that private financing is needed in order to meet climate targets that would require US$1.6 trillion annually from now to 2030.

Global metric for adaptation finance ‘unrealistic’

Peter McKillop, founder of US-based non-profit news organisation Climate & Capital Media, however, believes that having a global standard for tracking adaptation finance is not realistic. He said countries should still come up with their own methodologies.

“Companies and banks would all ideally love to have a global set of standards and metrics. But it’s going to come down to how these standards are actually implemented locally,” McKillop told Eco-Business.

He pointed to how flood-prone Colombia is coming up with its own set of metrics to measure the returns of climate finance. It also launched the Green Taxonomy which aims to provide clarity for those who invest in green projects and initiatives, by enabling them to understand whether an investment is classified as green within the country.

Despite the lack of a global standard for climate adaptation metrics that track adaptation, most developed countries have already widely incorporated climate considerations when analysing the credit quality of loans, like rewarding lending to undertakings that are environmentally sustainable such as green buildings and clean energy, said McKillop.

“Whether you’re the World Bank or an informed investor in countries which have their own taxonomies, you already know what the restrictions are for a project. This is what will attract the investors,” he said.