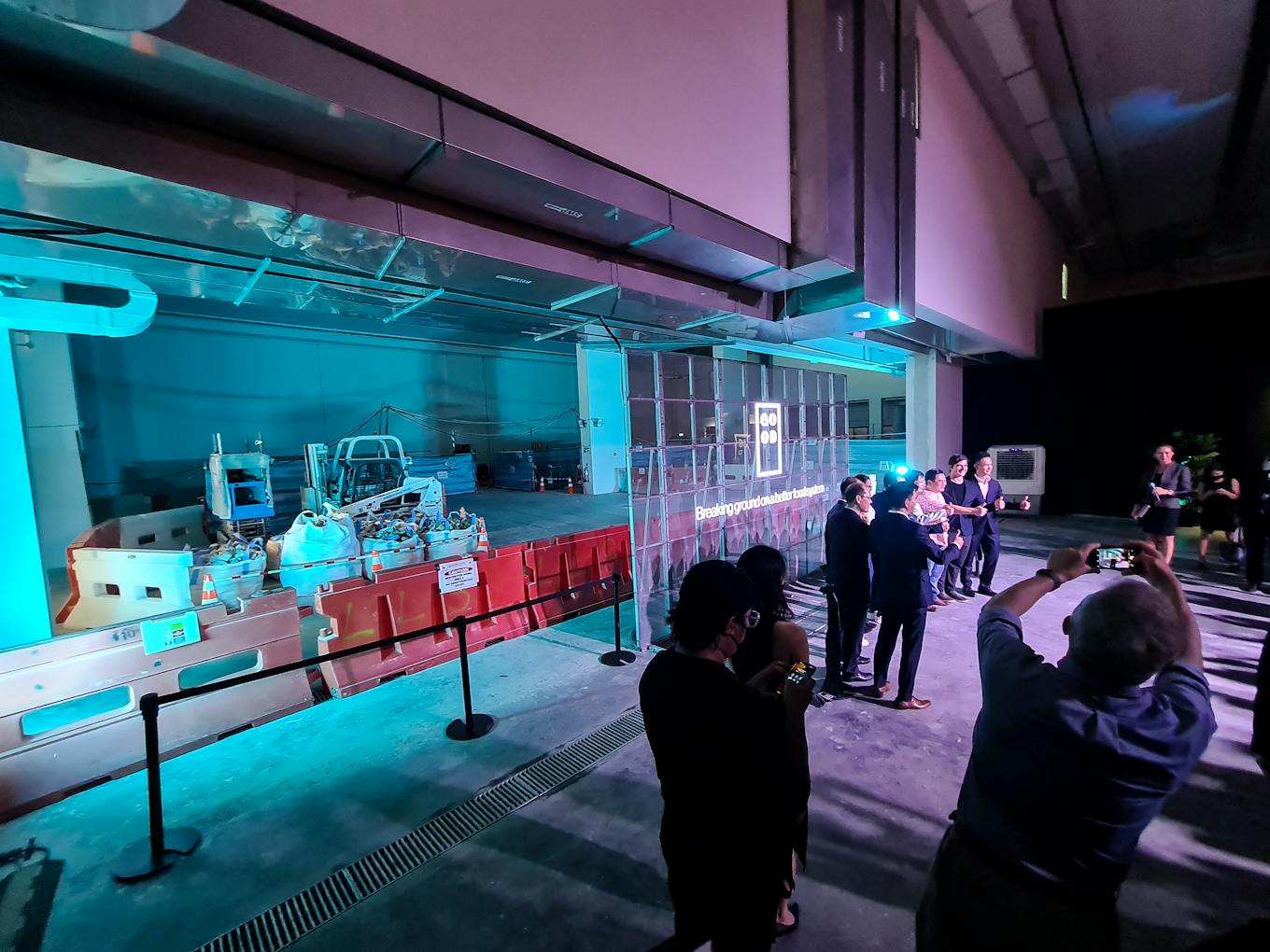

The 2,800m² high-ceiling facility in eastern Singapore was spick and span, but otherwise hardly resembled a food production plant, with bar tables, flashy projections and sampling plates of lab-grown chicken dishes for guests and media at the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In nine months, California-based start-up Eat Just is hoping to install a 6,000-litre vessel in the industrial building, to produce “tens of thousands of pounds” of meat products cultured from cells a year – all for the Singapore market.

“Demand is off the charts in Singapore – young people, old people, people who care, people who just love meat,” said Josh Tetrick, Eat Just co-founder and chief executive.

Eat Just is looking to install a 6,000-litre vat in its new manufacturing plant by early-2023 to supply cell-based chicken products to the Singapore market. Image: Eco-Business/ Liang Lei.

Singapore is the only country to have approved the sale of lab-grown meat; Eat Just is the only firm supplying it since 2020.

The ceremony for the firm’s new facility in June was held at a time when Singapore is missing a third of its supply of chicken – the most consumed meat in the city-state – as neighbouring Malaysia banned exports of the bird amid soaring prices.

“I wish we were producing thousands of pounds right now, this would have been quite the opportunity,” Tetrick said. As it stands, total production will be under 2,000 pounds this year, and sales of Eat Just’s chicken products are limited to a few restaurants and pop-up stands.

While cell-based meat could still be a decade away from reaching price-parity with animal cuts, the current food landscape has some things in the industry’s favour.

For one, the commodity price of common crops used for plant-based protein, the more established and generally cheaper form of processed meat substitutes, has been going through the roof.

Soy is now over 20 per cent more expensive compared to last June, while the price of wheat is 60 per cent higher – the cost of both rocketed after Russia invaded Ukraine. Both countries are agricultural powerhouses.

Pea harvests in Canada, the top producing country, also plunged last summer due to a drought, sending prices soaring.

“In some regions, such as Europe, there’s definitely a threat to the plant protein capacity,” said Dr Harini Venkataraman, a senior analyst in food and agriculture at Boston-based advisory firm Lux Research.

Firms in the industry say the impact has been manageable.

“We have seen increased transportation costs due to higher fuel prices, and increased pricing and scarcity for a few commodities that we use in relatively small amounts,” said Ethan Brown, founder and chief executive of Los Angeles-based firm Beyond Meat, at an earnings call last month.

Beyond Meat makes plant-based meat alternatives with protein from pea, mung beans, fava beans and rice. Brown added that the firm has recently managed to secure cheaper pea proteins.

Andre Menezes, co-founder and chief executive of Singapore-based Next Gen Foods, which produces a brand of soy-based chicken products, told Eco-Business it has been able to avoid increasing prices so far amid supply chain disruption and commodity price inflation.

“We are actively looking to reduce our prices in the near term, as we continue to benefit from our growth,” said Menezes of Next Gen Foods. The firm launched in Germany last week, its eighth country since 2021.

California-based Impossible Foods, which makes soy and potato-based burger patties, did not respond to queries by press time.

Nonetheless, high commodity prices, coupled with a general slowdown of the plant protein industry that has been attributed to market saturation and lacklustre customer response, could shift investors’ attention to technologies like cell-based and microorganism-derived meat alternatives.

“That is paving way for other alternatives to get more funding,” Venkataraman said.

It’s a trend that has already begun. Last year, plant-based protein firms received US$1.9 billion of investments, US$0.2 billion less than in 2020.

Funding for other technologies climbed from under US$1 billion to US$3.1 billion over the same period, according to data from alternative protein lobby group Good Food Institute (GFI).

Mycoprotein-based products, which derive protein from fungi, could have more room to grow too, according to Professor William Chen, director of the Food Science and Technology Programme at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

“It needs very low levels of technology, low levels of energy, low everything. But you have a very high yield in terms of fibres and proteins,” Chen said, adding that the technology is underrepresented in Singapore – a city-state that regards alternative protein as a core pillar of food security, and provides grants for local start-ups working on the technology.

Most of the funding for fungi-based foods last year has gone to Europe and the United States, GFI found.

“The consumer acceptance level is very high. Asian consumers eat mushrooms. But you talk about bacteria-derived proteins, people will think twice. You talk about microalgae, people will think twice, let alone lab-grown meat,” Chen added.

Common challenges

Alternative proteins that do not rely on plants are still affected by supply chain disruptions, even though they are less encumbered by price fluctuations. Tetrick said Eat Just is looking at a 4 to 6 per cent increase in equipment costs.

While Forbes had reported last year that Eat Just was looking to go public by early-2022, Tetrick said the stock market situation in the US has not been optimal, and will re-evaluate its prospects at the end of the year.

“There are a few milestones that we want to continue pursuing internally,” he added.

If cost is an issue for plant-based proteins, it would be an even bigger issue for cultured meat and fermentation-based food products.

“The capital investment is sometimes very high, in the form of research and setting up manufacturing facilities,” said Venkataraman.

“Microbial-based protein is not low-tech. You can’t set up such bioreactors everywhere. You need skilled people to operate them, even if the automation level is high,” added Chen.

Meanwhile, a 2021 industry report found that cell-based meat is 100 to 10,000 times more expensive than animal meat currently.

There is also no clear indication that another country will follow Singapore to approve the sale of cell-based products, though the United States is seen as a front-runner. Regulations surrounding microbial-based protein are more varied across markets, according to a GFI report.

Similarly, consumer support isn’t guaranteed for any new protein products.

“We need to do so much more research to understand consumer preferences,” said Assistant Professor Sonia Akter from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore, adding that cultured meat could take years before it is palatable for the mainstream.

Policy

More governments, mainly of richer nations, are throwing their weight behind alternative protein development, as concerns over food security mount.

The European Union is warming to the idea of a regional protein strategy, after calls by member states such as Austria and Netherlands to bolster plant protein production amid the Russia-Ukraine crisis.

Netherlands committed US$63 million to researching and producing cultured meat in April.

In Asia, China’s 2021 to 2025 economic development plan called for research into alternative proteins. China is the world’s largest importer of food, and its local pork production has been stymied since 2018 due to an outbreak of swine fever.

“With technological advancements and growing consumer demand for sustainable foods, alternative proteins have the potential to supplement Singapore’s agricultural productivity and contribute meaningfully to our “30 by 30” goal,” said Singapore’s sustainability and environment minister Grace Fu at Eat Just’s ribbon-cutting event. Singapore wants to produce 30 per cent of its food by 2030, up from 10 per cent today.

Experts said alternative protein is one of many tools to ensure food security, among others like precision agriculture, climate-resistant crops and ensuring fairer distribution of food. Solutions must be tailored to local populations, economics and tastes, they added.

A simpler way to shore up protein security could simply be getting people to eat more legumes and pulses – essentially raw materials that go into plant-based meat alternatives, said Akter.

“If we are including those proteins more in our diet, then we can reduce our dependence on any single type of protein and improve our food system’s resilience,” she said.

But Akter added she couldn’t tell yet what is the more feasible route – persuading consumers to change their often stubborn preference for meat, or opt for heavily-processed plant-based products, which more closely resemble nuggets and burgers, to price parity faster.

Beyond funding, governments may have to do more to ensure that the sustainability promises of alternative proteins are met – such as preventing price fixing should the alternative protein industry grow big and oligopolistic.

“In the United States, you have price-fixing issues with the meat industry all the time,” said Dr Jan Dutkiewicz, a food researcher at Harvard Law School. US lawmakers asked its Federal Trade Commission to investigate large beef firms for price fixing last month.

Dutkiewicz said antitrust measures could help, along with efforts to keep some intellectual property in the public realm, in the case of alternative proteins.

“Given that alternative protein is very much a consumer-focused technology, governments will have to tinker at the edges with various push-pull strategies in order to wheedle public good out of it,” he added.

What about the promise that alternative proteins are more efficient than livestock rearing, and can free up more land?

“What is done with that extra land is entirely a matter of policy – whether that land gets used to produce more crops, whether it is used for land sparing or rewilding schemes, or whether it gets turned into a parking lot,” Dutkiewicz said.