Just last month, transition-washing was singled out as part of a new wave of greenwashing in Asia in a set of guidelines launched by ClientEarth and Asia Investor Group on Climate Change (AIGCC).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

This emerging variant of greenwashing applies to transition finance, which unlike green finance, is intended to help brown sectors become greener. Transition-washing occurs when sustainable finance is used to fund carbon-intensive companies that do not use the capital to pivot their businesses away from fossil fuels.

“There is an inherent risk of being perceived as transition-washing if there isn’t an accepted understanding of what constitutes a credible transition,” said Indranee Rajah, Singapore’s second minister for finance and national development at International Capital Market Association (ICMA)’s Annual Conference of the Principles held on Wednesday (28 June).

“

Many existing taxonomies currently focus on green [finance]. We need standardised definitions of what can be credibly considered transition [finance] to further lower the barriers to entry for private capital.

Indranee Rajah, minister in the Prime Minister’s Office, second minister for finance and national development, Singapore

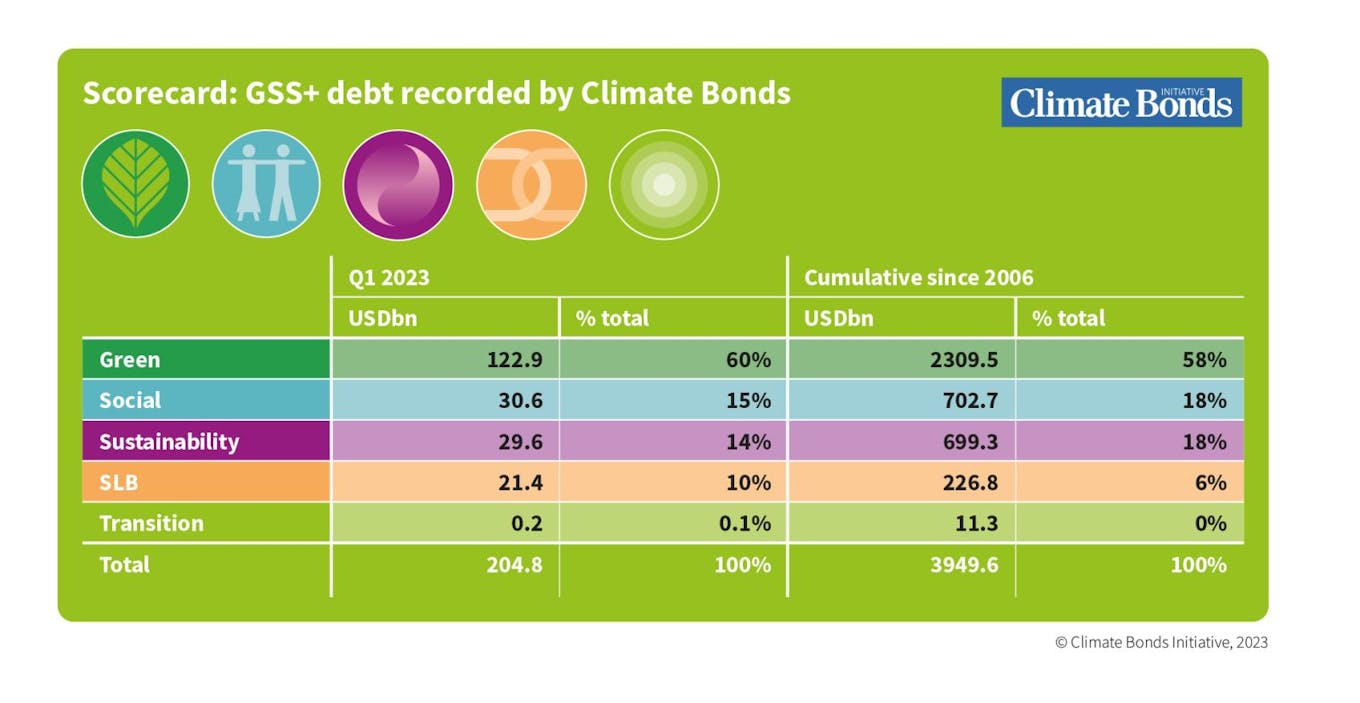

Within the sustainable debt market, transition-labelled bonds currently constitute the smallest theme and continue to see little pick up, compared to green, social, sustainability, and sustainability-linked (GSSS) bond issuances.

In Q1 2023, transition bonds added US$236 million to the entire sustainable debt market, or 0.1 per cent of the total market volume. Acccumulatively since 2006, the transition theme made up a negligible amount of the market. Source: Climate Bonds Initiative

To address the dismal capital flows into such transition finance mechanisms, global efforts to establish a common understanding of transition finance are starting to emerge.

In 2020, ICMA first published its guidance for transition finance and climate-themed bonds, which it updated last week. The latest edition acknowledges the development of climate transition guidance in certain jurisdictions and outlines expectations of what transition-labelled instruments should entail.

The guidance emphasises that financing from climate transition-themed bonds should be directed towards enabling an entity’s greenhouse gas emissions reduction strategy in line with Paris agreement goals of keeping global warming well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

In 2021, Japan built on ICMA’s initial guidance to provide one of the first guidelines on transition finance. Last year, China also indicated its intention to explore transition finance instruments and establish standards aligned with the framework developed by the G20’s Sustainable Finance Working Group.

Earlier this month, the European Union (EU) enhanced its sustainable finance framework, which now includes clarifications around transition finance and recommendations for how to facilitate its growth.

Set to launch later this year, Singapore’s sustainable finance taxonomy will provide clear definitions on what constitutes “green”, “transition”, and what constitutes neither, said Rajah. She added that defining transition finance is especially important for the region, where there remains a growing demand for energy.

Unlike the EU, the Singapore-Asia taxonomy will adopt a “traffic light” approach to classify economic activities based on their level of contribution to climate change mitigation, differentiating green (environmentally sustainable), amber (transition), and red (harmful) activities.

Rajah announced that the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has launched a public consultation on the detailed criteria for financing the early phase-out of coal-fired power plants, which the central bank’s chief sustainability officer made mention of last month. The feedback will be incorporated into the forthcoming Singapore-Asia taxonomy.

The problem with the sustainable bond market

The rapid growth of GSSS bond issuances – which made up a trillion-dollar market in 2021 before shrinking slightly last year – has not coincided with similar growth in social and environmental outcomes.

“During the time that [the green bond] market has developed, emissions have continued to increase. And when we look at the issuers of green bonds, a significant portion of them have continued to increase their emissions despite having issued a green bond,” said Cedric Rimaud, senior credit analyst, Asia Pacific, Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute, at a panel discussion on addressing greenwashing concerns at the event.

“We must remember why this market exists. It’s because we want to limit greenhouse gas emissions,” Rimaud said.

“

The existing ICMA principles and frameworks that are being put in place are sufficient to allow for credible transition projects, it is all about setting ambitious targets based on scientific methods and delivering on these objectives.

Cedric Rimaud, senior credit analyst, Asia Pacific, Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute

To prevent greenwashing, and increasingly transition-washing, these GSSS bond issuances need to be considered in a wider context of a company’s transition strategy.

For instance, a power company could be issuing green bonds to finance a solar photovoltaic (PV) power project, which is generally conceived as green, but plans to spend four times more on thermal power than renewables. “Even if the instrument is green, and finances or refinances something that is generally accepted as green, it’s not a coherent picture,” said Sheng Ou Yong, a green bonds and environmental, social and governance (ESG) analyst at BNP Paribas Asset Management, who spoke on a separate panel.

He contrasted this with an example of a global chemicals manufacturer – chemicals being one of the hardest to abate sectors – that wants to issue a green bond that is directly related to its US$8 billion per year capital expenditure to transition from a fossil-fuel based feedstock to produce chemicals, to one where more than half of its chemical sales come from renewable feedstock by 2030. In Yong’s view, this green bond issuance has “perfect coherence” as it contributes to the achievement of the issuer’s decarbonisation ambitions.

But not all investors engage as actively with issuers as Yong does, pointed out Rimaud.

“Some investors are just passively following ESG indices that sometimes contain issuers that clearly should not be in that index. We’ve seen instances where there are some brown activities still making their way into ESG indices,” he said.

Such indices are therefore misrepresentative for investors that want to put their money to work in an investment that would reduce greenhouse gas emissions, said Rimaud.

Many index providers, the four largest being S&P Dow Jones Indices, MSCI, FTSE Russell and Bloomberg, often use ESG ratings – provided either in-house or through a specialist third-party provider – to decide what securities to include in their ESG benchmarks, which influence billions in sustainable investment.

As a result, regulators globally have started to develop regulatory approaches for ESG data providers. Japan released the world’s first code of conduct for ESG data and rating products last year. The United Kingdom also has a draft code of conduct under way.

Singapore is the latest country to throw its hat in the ring, launching a public consultation on its own code of conduct for the sector. MAS will take a “phased and risk-proportionate regulatory approach”, starting with a voluntary code of conduct for the industry, before consulting on a more formalised framework in the future as the central bank continues to monitor global regulatory developments, said Rajah.

Yong acknowledged that smaller asset managers may not have the resources that BNP Paribas has – like the luxury of a 30-person ESG analyst team which he is part of – to assess the impact of potential investments. In such cases, they need guidance from ICMA and other institutions to make informed decisions.