The Yamal Peninsula is a vast expanse of tundra jutting into the Arctic Ocean in Siberia, and Russia’s biggest natural gas reserve, holding 20 per cent of the planet’s known natural gas.

The brutal, harsh landscape is home to the world’s largest remaining group of nomadic reindeer herders, the Nenets, while the waters around the 700-kilometre-long peninsular support a globally important fishery.

This remote place finds itself at the intersection of great power politics and issues of human survival. The peninsula is a fragile ecosystem that holds one of the last great reserves of hydrocarbons, reserves that are being made accessible by anthropogenic climate change.

Development of the region, which is being driven by the competing interests of world powers, threatens the traditional way of life of the Nenets and could exacerbate the impacts of climate change.

Strategic vision

One of those powers is China, whose state enterprises have invested in Yamal LNG, a natural gas extraction, liquefaction and export project. Yamal LNG’s output capacity is around 16.5 million tonnes per year, according to Novatek, the project’s majority owner.

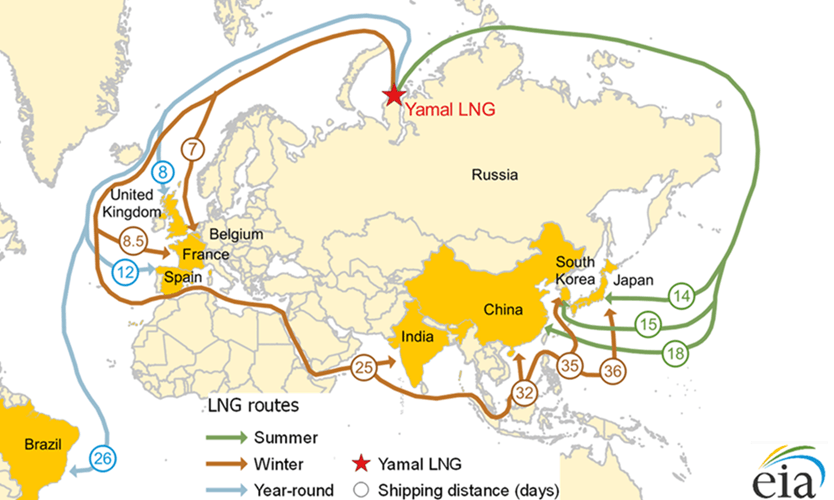

It was officially opened in December 2017, sending its first cargo of liquefied natural gas (LNG) along the Northern Sea Route to Boston in the United States, after being sold on the spot market. Details of purchase contracts have not been disclosed, but 96 per cent of the LNG produced by the plant has been contracted under 20-25-year agreements, with most of the gas going to China and Japan, according to Novatek.

Yamal LNG met the developers’ tight deadlines in large part because Chinese investors stepped in with funding after the US and Europe imposed sanctions on Russia for its annexation of Crimea and involvement in the Ukraine.

China National Petroleum Corporation and China’s Silk Road Fund own nearly 30 per cent of the Yamal LNG project. This is a practical investment for China, where demand for natural gas is rising as the government looks to reduce air pollution by switching coal and oil heating to natural gas.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicts China will burn nearly 60 billion cubic feet of gas per day in 2040, up from nearly 20 billion cubic feet in 2015. Although it has ample reserves of its own, including the world’s largest reserves of recoverable shale gas, China’s demand for LNG imports is likely to rival Japan’s, currently the world’s biggest importer of gas.

Arctic access

Yamal LNG shipped its first exports around the time China’s State Council Information Office published the country’s first Arctic Policy white paper on January 26.

China’s Arctic Policy stresses shipping and fishing rights among its interests in the region.

“As a result of global warming, the Arctic shipping routes are likely to become important transport routes for international trade,” the policy document said, adding that China hopes to work with all parties to build a ‘Polar Silk Road’ by developing Arctic shipping routes, a phrase that ties the Arctic into China’s expansive Belt and Road vision of a global infrastructure and transport network.

Meanwhile, Russia is formulating a shipping policy that excludes non-Russian ships from transporting hydrocarbons along the Northern Sea Route. This route passes through the country’s exclusive economic zone of 200 nautical miles. The ban would be a boon to Russian shippers.

With fish stocks moving northward as seawater temperatures rise, China’s government wants to ensure its fishing fleets have access to the Arctic’s high seas as sea ice retreats.

“China supports efforts to formulate a legally binding international agreement on the management of fisheries in the high seas portion of the Arctic Ocean,” the Arctic policy document said.

China is positioning itself, through its many regional involvements, to ensure that any such agreement reflects its interests as a “near Arctic state” and not just those of Russia, the US, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Canada and Iceland.

Development dangers

The impacts of shipping in the Arctic’s fragile environment have been the subject of much study and policymaking as the Northern Sea Route looses sea ice and becomes more accessible.

International Maritime Organization issued a Polar Code in 2017 that restricts oil, sewage and garbage discharges in Arctic waters. It also set out requirements for the design, construction and equipment used by polar ships. Black carbon emissions from vessels burning heavy fuel oil are also of concern, because the pollutant settles on ice and snow and increases the rate of melting.

The special cargo ships built to service the Yamal project burn LNG as a fuel. They don’t emit black carbon and produce less emissions. Perhaps the biggest risk of Arctic shipping is from accidents in the harsh and dangerous environment of moving ice flows and major storms.

The capacity to clean up an oil spill in the remote region is extremely limited and would likely have long term impacts, as oil takes much longer to break down in the cold. Arctic countries have signed an agreement to provide search, rescue and clean up assistance in the event of a disaster.

In a breakthrough for marine conservation in December 2017, nine major fishing nations, including China and the EU, signed up to a 16-year ban on commercial fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean, north of the Yamal peninsula. This area is not yet commercially fished. The ban will preserve fish stocks while studies are made of this barely-understood ecosystem.

Fish nursery dredged

However, the development and shipping activity associated with Yamal LNG are already threatening the future of the peninsula’s fishing industry.

The Yamal gas export terminal is at Port Sabetta on the eastern edge of the Yamal peninsula. Ships servicing the port require a channel that’s around 300 metres wide and 15 metres deep, which was dredged to provide access.

To achieve this in the shallow waters of the Gulf of Ob, 23 dredger vessels removed 70 million tonnes of seabed between 2014 and 2017, according to the Russian Federal Agency for Maritime and River Transport.

Dredging the channel has changed the gulf, a unique estuary with global significance as the most productive fish nursery in the Arctic territory, according to environmental impact assessments.

The Gulf of Ob “is the most important place in the world for a number of valuable fish species,” warned experts in the Russian publication Fisheries in 2013, as the Port Sabetta project got underway.

They recommended an alternative site where the port would do less harm to sturgeon, muksun, smelt and many other white fish species that breed there, but did not prevail.

Salination

The Russian Federal Agency for Maritime and River Transport said on January 6 that it is now undertaking “measures to eliminate the negative impact on the state of aquatic biological resources and their habitat,” including reintroducing juvenile fish into the area.

But the greatest concern at the moment is the potential for salt water to intrude deeper into the gulf as a consequence of the new channel, according to Vladimir Chuprov, director of the Energy Program at Greenpeace Russia.

“If it becomes a new ecosystem with more saltwater, it will possibly lead to changes in the biodiversity of fish species,” Chuprov said.

Staple foods at risk

For the Nenets, Yamal’s native people, the project’s impact on the nutritious, salmon-like muksun is a major concern. Chuprov noted the muksun fishery is currently experiencing a collapse, although overfishing is suspected as the main cause.

Fishing for muksun was banned in Yamal in 2014, according to Pavel Sulyandziga, member of the United Nations Working Group on Business and Human Rights and chairman of the Board of Batani, a development fund for indigenous peoples.

Despite the ban, muksun numbers have failed to recover. It is still unclear whether this is because of the construction of Port Sabetta, persistent pollution caused by mining and infrastructure development, or other causes, such as illegal harvesting. In response, fishermen have begun targeting other species.

Industrial development on land also presents serious threats to Yamal’s Nenets.

The political leadership in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Region is committed to representing the interests of the Nenets people. Sulyandziga is now seeking political asylum in the US following threats against him and his family due to his indigenous rights campaigning.

The Nenets are successful nomadic reindeer herders. They are well organised, and benefit from economic compensation from the extractive projects in their ancient land. However, the infrastructure projects still compete for land that herders need to raise reindeer. “Naturally it is a big problem if there are reindeer but no pasture,” he said.

This story was originally published by Chinadialogue under a Creative Commons’ License. Read the full story.