The widespread effects of climate change are putting increasing pressure on businesses to integrate climate considerations into their strategies and operations. Linking executive compensation to climate-related objectives, when implemented correctly, can serve as a useful lever in aligning behaviour and practices with climate goals.

In a recent virtual forum hosted by the Climate Governance Initiative in collaboration with the World Economic Forum, I had the opportunity to moderate discussions about the imperatives for tying executive pay to climate-related strategies. My fellow panellists, which comprised of directors of global industry-leading companies and asset managers, shared their challenges and risks when broaching the subject with board members and remuneration committees.

For a majority of public-listed companies, especially in developing countries, pressure is mounting from investors, multinational clients and regulatory stakeholders for them to cut emissions and address climate risk. There is a growing global consensus among investors on how companies should incorporate climate considerations into board decisions, as indicated by strong participation in investor groups such as Climate Action 100+ and the Investor Group on Climate Change (IGCC) .

With climate considerations now underscoring investor strategy, investee companies are expected to adopt climate as an underpinning strategy instead of just a nice-to-have addition after other performance metrics are met. Climate safeguards should, in fact “be adopted with as much priority as capital adequacy requirements,” argued Natasha Landell-Mills, Head of Stewardship and Partner at global thematic investment management firm Sarasin and Partners. Investors are voting with their feet, choosing to oppose the reappointment of remuneration committee members or abstain from voting if they do not see climate considerations underpinning firms’ strategies.

A measured approach

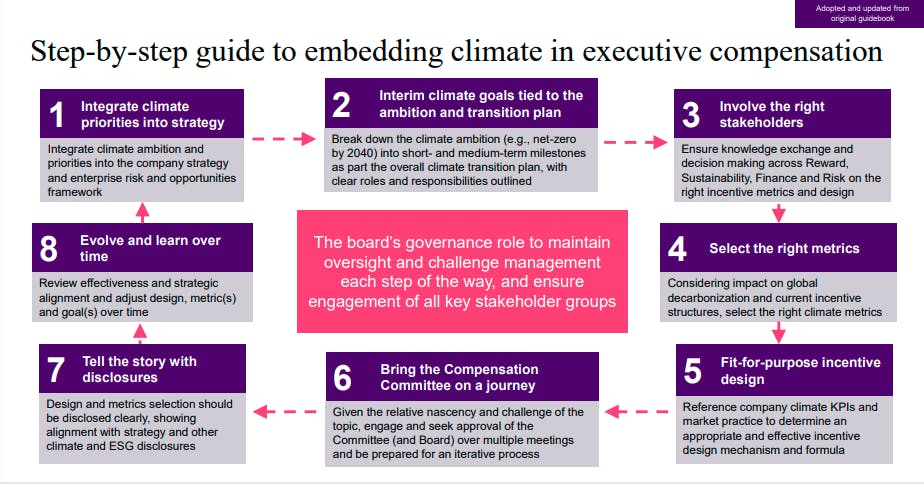

Where should boards and management begin? First, they need to understand what their starting point is. Climate priorities must be decided upon and integrated into the company’s strategy, with baseline data measured, long-term targets set and interim climate goals clearly defined. The following graph offers a step-by-step guide on embedding climate priorities in executive compensation, extracted from the 2023 addendum of WTW’s Executive Compensation Guidebook for Climate Transition, produced in partnership with the Climate Governance Initiative.

The guidebook also offers companies guiding principles for selecting and implementing climate-related metrics. These include ensuring that the metrics are material to long-term value creation and risk mitigation for the business, can be easily and reliably measured, are comparable with industry standards and can be used to provide clarity, transparency and consistency towards the company’s climate progress.

Having measurable standards is essential in ensuring that progress towards climate goals can be tracked. The more rigorous the measurement system, the more effective incentive schemes can be designed, as underscored by Nicholas Allen, the Chairman of real estate and asset manager Link Asset Management and Independent Non-Executive Director at both Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing, as well as energy firm CLP Holdings. This resonates with WTW’s guidebook, which advocates for a rigorous approach toward climate metrics. Such metrics should not only be consistently measured and tested by management, but also subject to comprehensive review and vetting by the board, so that they meet assurance standards and withstand external scrutiny, and prove to be material to the business to be of value to investors and stakeholders.

Incentive schemes should also account for companies outperforming or achieving climate-related targets faster than expected, said Angeles Garcia-Poveda, Independent Chair of the Board at French electronics company Legrand, and Advisory Board Member of Climate Governance Initiative. Oftentimes, schemes are designed with underperformance rather than overperformance in mind, she pointed out, a system that would hinder the ability to recognise and reward executives who go beyond the bare minimum to achieve climate targets. We are seeing progressive companies incorporating time as a multiplier in their incentive plans; with upward or downward adjustments to payments if climate goals are achieved ahead of schedule or delayed, respectively.

Addressing short-termism

Climate horizons often outlive the tenures of chief executives, senior management and potentially even directors, making short-termism one of the biggest challenges in effectively implementing climate-linked executive pay. If long-term decarbonisation goals and measurable near-term targets are not well-aligned, executives could end up chasing short-term numbers that are detrimental to the company’s longer-term climate targets.

A potential solution to this would be to apportion climate-focused remuneration across various functions and departments within an organisation, looking beyond only senior management executives. This will take time as each department’s climate-related impact and opportunity is assessed, but the exercise can help remuneration committees ensure that executives throughout the company are not rewarded for behaviour contrary to climate goals.

But given the variation in climate maturity across different geographies and industrial sectors, boards and senior executives must also be cognisant of the readiness of their companies to implement climate-driven change. High-growth companies, for instance, may not be able to commit to an absolute decrease in baseline emissions but can instead follow a pathway that leads to a decrease in emissions intensity, or relative emissions. Different sectors may also require different levels of disclosure or granularity of data to better measure progress on climate goals.

It is also worth noting that global standards for quantitative measurement are still evolving, and that internationally standardised metrics for climate-related disclosures are being refined. For instance, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) published its much-anticipated disclosure standards in June this year, and a transition implementation group is being put together to discuss the implementation of the standards. The European Commission has adopted the European Sustainability Reporting Standards and in Southeast Asia, the second version of the ASEAN Taxonomy was recently released.

Spotlight on Asia Pacific

Listed companies in Asia-Pacific are lagging, but are catching up with their global counterparts in incorporating ESG and Climate measures in their executive compensation programmes. Based on the companies that disclose information on the use of incentive metrics, European companies continue to lead the pack with 91% using at least one ESG metric in their incentive plans, followed by U.S. companies at 69 per cent. Whilst most companies in Europe and North America disclose information on metrics in incentive plans, only 62 per cent of companies in APAC did so; and of those companies 63% had a linkage between ESG measures and incentive plans.

Conclusion

This sensitivity to the nuances of climate standards and disclosures is something that requires an improvement in climate literacy throughout the entire organisation, from board members to employees and third-party vendors. At the board level, climate expertise should not be limited to just one or two board members. Instead, each and every director should develop an intellectual curiosity and make a personal commitment when it comes to learning about climate impact.

While linking climate strategies to remuneration is important, it is just a starting point for deeper conversations about climate goals and how each function within the organisation can best align itself with them. It is not enough for only senior executives to be aware of the financial and operational impacts of climate change when it takes a whole organisation to translate climate strategies into reality.

Climate action must also be seen as a good business imperative, not a moral one. While moral imperatives are admirable motivating factors, they rarely inspire long-lasting change in the way that tangible financial and non-financial benefits do. Business leaders must realise that a good sustainability strategy is integral to sustainable profits.

Finally, it is important not to let perfection be the enemy of the good. Even though the playbook for climate-related disclosures is are still evolving, especially surrounding Scope 3 emissions, companies should not take this as a sign to shy away from climate action until the rules are set in stone. Instead, this is an opportunity for remuneration committees to incentivise the right behaviours that will accelerate companies towards their climate goals.

Shai Ganu is the global leader for executive compensation and board advisory business at global advisory, broking and solutions company, WTW. He serves on boards, human resources and sustainability committees of leading companies and not-for-profit organisations in Southeast Asia.

This article was first published on Bursa Sustain, Bursa Malaysia’s one-stop knowledge hub that promotes and supports development in sustainability, corporate governance and responsible investment among public-listed companies.