Although Shell was aware of the catastrophic consequences of climate change from burning fossil fuels back in the 1980s, moving into renewable energy then would have crippled the company, a senior Shell executive said at an event in Singapore on Friday.

Speaking at a Shell-sponsored debate on the future of energy at Singapore University of Technology and Design, Maarten Wetselaar, the firm’s director of integrated gas and new energies, also said that legal action taken against fossil fuels firms by countries suffering from the effects of climate change was a “waste of society’s money and time.”

At the event recorded live on Twitter, Wetselaar was asked how one of the world’s largest oil companies could expect to be taken seriously in a discussion about decarbonisation when it had ignored its own research that warned of climate change impacts as early as the 1980s, and in the years since has pumped billions into fossil fuels extraction and been linked to spending on lobbying against climate action.

“

It is certain that if we’d spent all of our capital in the 1990s building solar panels, we would have gone bankrupt long before today.

Maarten Wetselaar, integrated gas and new energies director, Royal Dutch Shell

Addressing an audience of mostly students in Singapore yesterday, Wetselaar said that the world has intervened “very late” to tackle climate change, but solving the energy challenge would take collaborative action now rather than “going back 30 years ago and saying who should have done what.”

Maarten Wetselaar: “Everybody should have done more—and didn’t.” Image: Shell on Twitter

“Everybody should have done more—and didn’t,” he said.

“It is certain that if we’d spent all of our capital in the 1990s building solar panels, we would have gone bankrupt long before today, because our customers did not want to buy green energy at high prices at the time,” said Wetselaar, who has worked for Shell since 1995.

Wetselaar also said that blaming energy companies for the damage caused by climate change did not help solve the problem.

In 2016, the Philippines Commission on Human Rights launched a landmark legal case against fossil fuel companies for violating the human rights of its citizens by driving climate change, and this week the government of the low-lying Pacific nation of Vanuatu said it was also considering taking legal action against fossil fuel firms, banks and governments that knowingly contribute to the climate crisis. Five other island nations have sought legal redress from the world’s oil majors.

“The action that needs to be taken [to transition to a low carbon economy] is by a complex system of government, consumers and companies. To sue a single actor in that system is a waste of society’s money and time. But people should feel free to do what they want,” Wetselaar said.

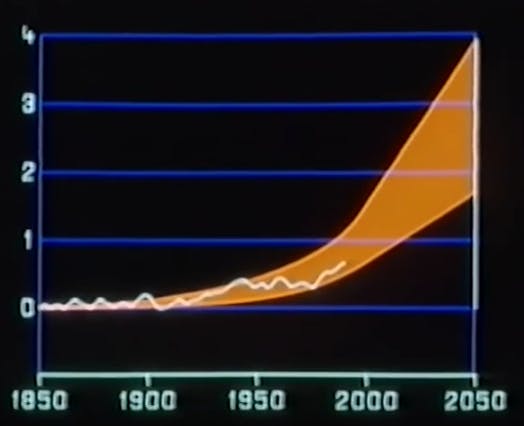

Shell’s 1991 video warned of global warming from burning fossil fuels. Image: Climate of Concern

In 1991, Shell produced a video titled Climate of Concern, obtained by a Dutch online media outlet De Correspondent last year. The video warned that increased burning of fossil fuels would warm the world and result in extreme weather, floods, famines and “greenhouse refugees”. The film referred to data from the company’s own scientists that predicted climate change “at rate faster than at any time since end of the ice age.”

The filmed warned that to delay action to mitigate the effects of climate change—even though the firm believed that global warming wasn’t scientifically certain then—would be “irresponsible”.

In 1986, a separate report produced by Shell scientists, also obstained by De Correspondent last year, urged the company to respond to the early warnings, even if the evidence for man-made climate change from greenhouse gases hadn’t been proven until the 2000s. “It could be too late to take effective countermeasures to reduce the effects or even to stabilise the situation,” the report read.

“

If we stopped producing oil and gas tomorrow we would have an economic crisis. We would have famine and we would have a world war. There is no way this world can turn without oil and gas.

Oil, gas and the energy crunch

Earlier in the debate, Wetselaar said that double the amount of energy would be needed to provide for a population that will have reached 10 billion by the end of the century. But he warned that if the current energy supply system is doubled, “this planet will be an unliveable place for our children and even for ourselves.”

He cited solar, biofuels, hydro, wind, and hydrogen as energy sources that will make up an important part of the energy mix in the future, but he added that “there is also an opportunity for oil and gas,” particularly in places that cannot be electrified.

“If we stopped producing oil and gas tomorrow we would have an economic crisis. We would have famine and we would have a world war. There is no way this world can turn without oil and gas,” he said, citing the many everyday functions that depend on fossil fuels, such as heating, aviation, roads, and medicine.

But Wetselaar was frank about the need for decarbonisation, telling his audience: “We know we cannot scale up oil and gas production, we need to scale it down. So it’s a task of all of us to change the way we consume energy. And it’s the task of companies like us to seduce our customers to decarbonise their lives.”

“

We cannot subsidise our way out of climate change.

Shell shareholders are human too

Wetselaar was asked why the rhetoric of energy companies like Shell should be believed when they ultimately answer to their shareholders.

He said that shareholders were also human, worry about climate change and “want to leave a better world for their children.” He added that Shell’s shareholders “also quite like to have a dividend” but that a low carbon future and profitability were not mutually exclusive.

Wetselaar said that his job was to prove that new energy sources such as renewables were commercially successful, and can be scaled to the point that they have real impact. “We cannot subsidise our way out of climate change,” he said.

The event featured a live survey that asked followers of the hashtag #MakeTheFuture what needs to happen to tackle climate change quickly.

A switch to renewable energy was the most popular answer, with 53 per cent of respondents saying that more renewables was needed. A quarter (25 per cent) said more efficient energy, 14 per cent said capturing carbon and 8 per cent said more gas and less coal.