Sri Lanka is no stranger to economic strife, but the amount of foreign debt the country has accumulated and the problems it has caused have pushed the country close to ruin.

Last month, the island nation was unable to find US$78 million to pay the interest on the whopping US$50 billion it owes to foreign debtors. Missing the payment’s 30-day grace period on May 18 plunged Sri Lanka into what its central bank governor Nandalal Weerasinghe called “a pre-emptive default” for the first time in its history. Now nearly devoid of foreign exchange reserves, Sri Lanka has been unable to import sufficient supplies from the global marketplace, causing massive shortages, soaring inflation rates and civil unrest.

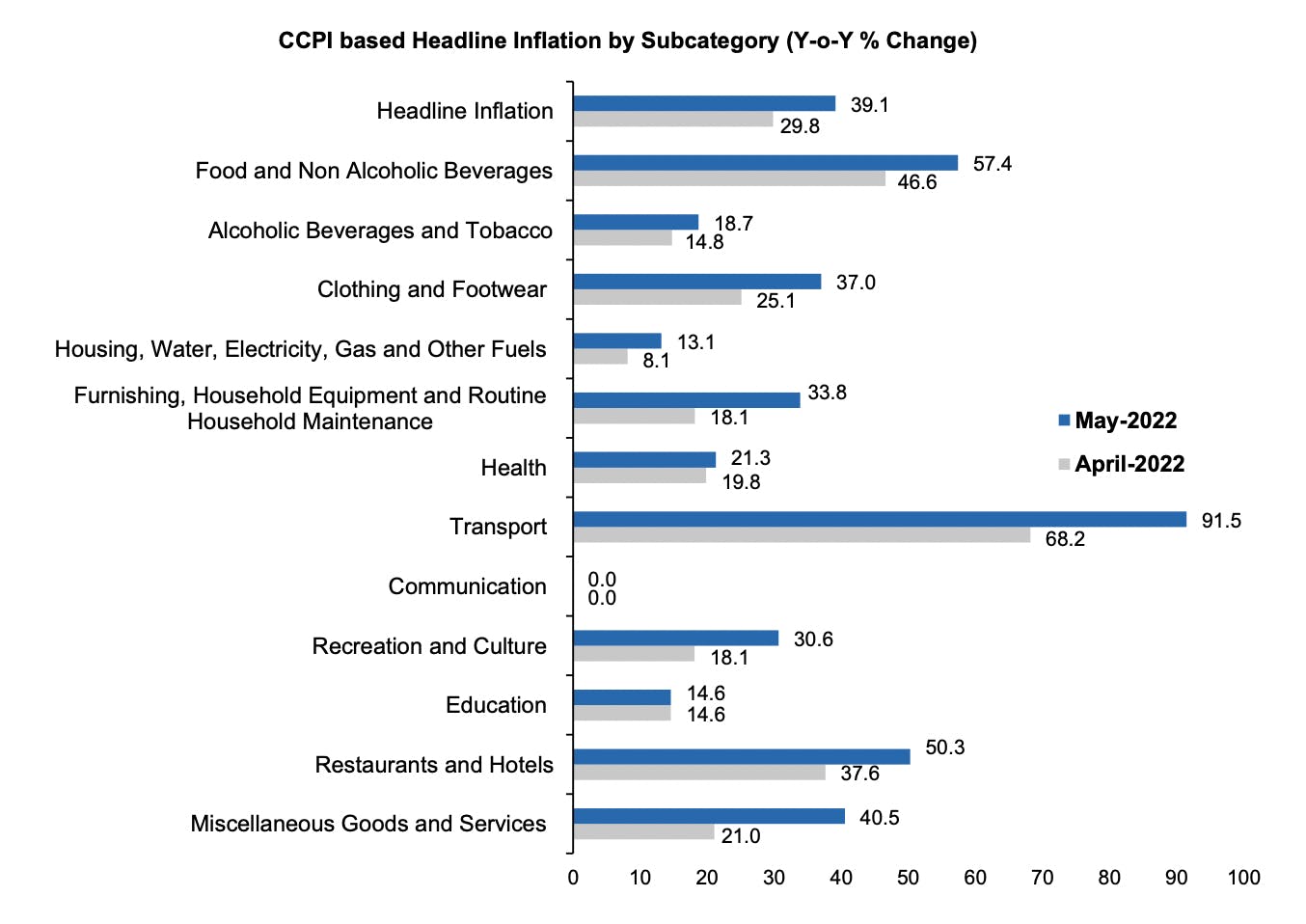

According to the latest Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI), inflation for food and non-alcoholic beverages is now at 57.4 per cent, up from last month’s 46.6 per cent. While Sri Lankans can still buy essentials from government-run low-cost shops, shoppers often leave empty-handed and are forced to go to private supermarkets where prices are many times higher.

Currently, a kilogram of rice which used to cost 80 Sri Lankan rupees (US$0.22) before the crisis could now set consumers back at least 500 rupees (US$1.39). A small tin of milk powder, which used to cost 60 rupees (US$0.17) could now be worth more than 250 rupees (US$0.70). With rapidly increasing unemployment and prices for staple goods, experts worry not only about the impending food shortages, but also its long-term impact on the nation’s health. Vulnerable groups like women, children and the poor will likely be disproportionately affected for years to come.

Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI) increases from April to May 2022 for goods and services. Image: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

“In 2019, a third of our preschool children were already malnourished or suffering from wasting or stunting. Moreover, our pregnant and lactating mothers have also been suffering from anaemia. The price of chicken, eggs, milk and other protein sources have risen. Thus, they may face problems reaching their protein and micronutrient needs. We can expect long-term impacts in the future,” said Jeevikaw Weerahewa, a senior professor at the University of Peradeniya’s (UOP) Department of Agricultural Economics and Business Management in an interview with Eco-Business.

The perfect storm

Many blame Sri Lanka’s financial troubles on the short-sighted policies pursued by the previous administration under then Prime Minister Gotabaya Rajapaksa, particularly his decision to turn the nation’s entire agricultural sector organic by 2030. To achieve this, Rajapaksa announced a blanket ban on synthetic fertilisers, pesticides and weedicides practically overnight in April 2021. While it was originally marketed as an attempt to improve soil and human health, economists argue it was more likely a misguided attempt to reduce imports and preserve dwindling foreign exchange reserves.

Since the 1960s, the Sri Lankan government has provided farmers with greatly subsidised chemical fertilisers, irrigation and extension services. Through these policies, yields for staple crops like rice more than tripled compared to traditional farming techniques, allowing the country to be mostly self-sufficient in the crop. However, Professor R. S. Dharmakeerthi, head of UOP’s Department of Soil Science said that these services, coupled with the lack of viable alternatives, have made Sri Lankan agriculture overdependent on agrochemicals. According to the study done by independent Colombo-based think tank Verité, 76 per cent of farmers frequently used chemical fertilisers, and amongst paddy farmers, their use was nearly universal at 94 per cent.

Following the agrochemical ban, rice harvests fell by 40 – 50 per cent, which severely endangered the nation’s food security. Furthermore, yields for tea, which accounted for more than 11 per cent of Sri Lankan exports in 2020, fell to its lowest in 23 years. This coupled with the tourism and remittance losses due to the pandemic and other ill-advised tax policies meant Sri Lanka quickly eroded its foreign exchange reserves and was soon unable to cover their food deficits through foreign imports.

Searching for solutions

With little remaining domestic food reserves and currency, coupled with record-high prices for fertiliser and food due to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict and global food crisis, Sri Lanka seems to have run out of options. Though it received its first consignment of humanitarian aid from India two weeks ago, which contained 9,000 tonnes of rice and 50 tonnes of milk, widespread hunger still seems inevitable. Nevertheless, Weerahewa said the government would distribute these supplies responsibly, and she urged Sri Lankans to seriously consider cultivating their home gardens to stave off malnutrition.

In Sri Lanka, rice is typically cultivated during the two monsoon seasons every year. The Maha, or “greater” season, usually results in higher yields and takes place between September to March, and the Yala, or “lesser” season, takes place between May to August.

On May 19, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe announced on Twitter that though “steps [were] being taken to ensure adequate [fertiliser] stocks for the Maha season”, farmers would likely have to do without this Yala season. This could seriously decrease the availability of rice seed, leading to recurring rice shortages for years to come. Hence, despite the prohibitive costs, Dharmakeerthi urged the government to continue importing and distributing as much chemical fertiliser as possible at subsidied rates. “Rice seed production must be protected at any cost. We can only cultivate enough rice with enough seeds, and must also prioritise export market crops like tea,” he said.

We have crisis, but also an opportunity. Let’s not go back to the same old drug and carve ourselves a more sustainable future.

Dr Ranil Senanayake, chairman, Rainforest Rescue International

Dharmakeerthi also advised that Sri Lanka must make concrete progress towards its target of cutting chemical fertiliser usage by 25 per cent by 2030 because its subsidies were costing the country 2 per cent of its foreign exchange alone every year. To achieve this, his team has been developing environmentally friendly technologies (EFTs) like soil test programmes adapted to Sri Lankan environments and slow-release biofertilisers, allowing farmers to better understand and meet their farms’ nutrient requirements in a more economical and environmentally sustainable way.

Furthermore, his team has also developed economically viable methods of producing biochar, a charcoal-like biproduct of agricultural waste which can not only sequester carbon, but also protect drier soils from moisture stress, especially during periods of water scarcity. Moreover, Dharmakeerthi reports that farmers are well aware that chemical fertilisers are unsustainable for the environment and human health, and are willing to pay slightly higher prices if an alternative solution can promise equivalent or greater yields. With field trials showing positive results, the professor states that the government can discourage agrochemical overuse by developing such industries, encouraging better cropping systems and instituting stricter land-use policies.

While most feel that Sri Lanka could never go 100 per cent organic, organic farming proponents like Dr Ranil Senanayake, chairman of conservation non-profit Rainforest Rescue International, say otherwise. He argues that Sri Lankan farmers should take this opportunity to wean themselves off from chemical fertilisers and transition towards more sustainable land management systems, like analogue forestry.

“We have a crisis, but also an opportunity. Let’s not go back to the same old drug and carve ourselves a more sustainable future. Scientists and farmers must come together and define a common path that everyone understands,” Senanayake said in an interview with Eco-Business.

First implemented in Sri Lanka by Senanayake in 1981, “analogue forestry” aims to rehabilitate degraded forest ecosystems by restoring its natural structure through plants which fulfil essential ecological functions but also provided local communities with food and income without the use of chemical fertilisers.

Apart from conventional organic certifications, products from farms using alternate land management systems like analogue forestry can be recognised by even higher standards like the Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC), thus allowing farmers to offset lower yields by charging higher prices. Furthermore, these land management systems can increase food variety, security and also enable farmers to provide educational and other value-added services and experiences, which would boost their revenue streams.

Additionally, Senanayake argued that given the impending energy shortage, climate crisis, and conventional agriculture’s heavy reliance on fossil fuels, switching to more sustainable land management systems might be inevitable. So, he urged farmers to start as soon as possible.

Regardless of which option Sri Lanka’s beleagured farmers choose, it is clear they cannot revert to the status quo.