As forced labour in Asia comes under fresh scrutiny, analysts say countries in the region must improve their human rights commitments and enforce the law more strictly, if they want to repair their reputations and avoid paying an economic price.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

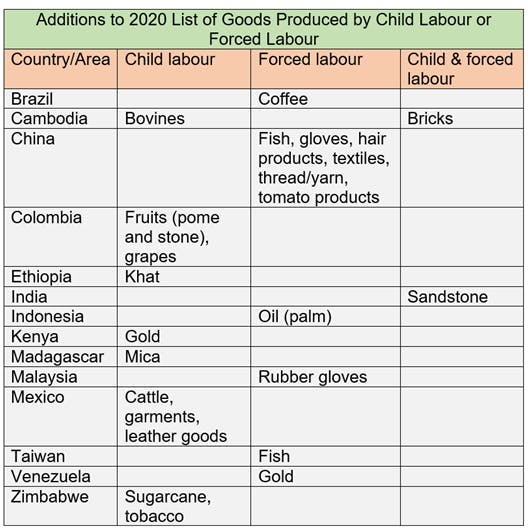

Goods from Asia made up nearly half, or 12, of the 25 new additions to the United States’ latest list of goods said to be produced by child or forced labour. They include Cambodian bricks, Malaysian rubber gloves, Indonesian palm oil, Indian sandstone, and fish from China and Taiwan.

China, with six goods newly added and a total of 17 goods on the list, was singled out by US Labour Secretary Eugene Scalia as having more goods made with forced labour than any other country “by a wide margin”.

Source: US Department of Labour 2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labour or Forced Labour

The US Department of Labour’s 2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labour or Forced Labour names goods and the countries that produce them, but does not mention companies.

The latest edition of the biennial list was released on 30 September—the same day another American agency, the US Customs and Border Protection, announced an import ban of palm oil from Malaysian company FGV Holdings due to forced labour.

Earlier last month, US Customs issued five import bans on cotton, textiles, apparel, hair products and computer parts produced by Chinese companies, the bulk of them in Xinjiang. The bans were due to forced labour of detained Uighur Muslims.

Unlike the US Department of Labour’s list, when it comes to forced labour, US Customs takes action against specific manufacturers and exporters, as well as specific merchandise. It does not generally target entire product lines or industries in countries or regions.

The United Nations’ International Labour Organisation estimates that 25 million people are in forced labour worldwide, of whom 16.5 million are in the Asia Pacific.

“

Brands that knowingly source a good from a country contained in the list, would be subject to more discerning customers. It is a reputational risk for the brand.

Andy Shen, senior oceans advisor, Greenpeace USA

What does inclusion on the list mean?

Addition to the Labour Department’s list—one of the most authoritative sources on the state of forced labour—mainly harms the reputation of countries or territories, said Andy Shen, Greenpeace USA’s senior oceans advisor.

Economic consequences are possible, if Western consumers base their shopping decisions on the list or if Western companies base their sourcing decisions on the list, he said.

“Brands that knowingly source a good from a country contained in the list, would be subject to more discerning customers. It is a reputational risk for the brand,” Shen said.

Inclusion on the list has played a major role in improving labour practices in Thailand’s seafood industry, and was a major factor in companies deciding not to source cotton from Uzbekistan, he said. Thai fish and shrimp, as well as Uzbek cotton, remain on the list.

Inclusion could also lead to further consequences.

US Customs uses the list when it evaluates and prioritises forced labour cases, Shen said. Citing Taiwan’s inclusion for fish in the latest list, he said brands are put on notice. “Importers that fail to prevent forced labour on Taiwanese-flagged vessels risk the diversion of fish from their supply chain.”

The list has also been used in trade litigation cases heard by the US Court of International Trade, such as civil suits to establish anti-dumping duties.

To get out of the list, countries must demonstrate improvement in their human rights commitments, said Sofia Nazalya, human rights analyst at global risk analysis company Verisk Maplecroft.

This includes, for example, assessing the adequacy of programmes to prevent child labour, or adequacy of penalties for child labour violations, she said.

States can also demonstrate robust enforcement of existing laws by ensuring that their labour inspectorates are adequately funded and resourced. “Tackling corruption amongst labour inspectors is another important consideration—in countries like Cambodia, Myanmar and the Philippines (included in the Department of Labour’s list), this remains a significant hindrance to effective enforcement,” said Nazalya.

“

While previously companies exposed to child labour risks would consider reputational risk to be a primary concern, increasingly they will have to factor in legal, financial and operational risks if found to be linked to such violations.

Sofia Nazalya, human rights analyst, Verisk Maplecroft

On the impact of inclusion on the list, Nazalya said corporates will seek to avoid goods that are tainted with the association to child or forced labour. This is due to environmental, social and governance (ESG) related legislation becoming more mainstream and widespread.

“While previously companies exposed to child labour risks would consider reputational risk to be a primary concern, increasingly they will have to factor in legal, financial and operational risks if found to be linked to such violations,” Nazalya said.

Companies tainted with such links risk major losses in revenue, she said.

How Taiwan plans to respond

While China denied the issue of forced labour and said the US’ actions violate the rules of international trade, Taiwan’s Fisheries Agency told Eco-Business it will take steps to address forced labour on board its fishing vessels.

“While it is understood that (the US’) list does not restrict sales of the included products, the reputation of Taiwan’s fisheries is very much tarnished and customers’ willingness to buy our fish products may be affected,” a Fisheries Agency spokesperson said.

Taiwan has the second-largest distant water fishing fleet in the world and is home to Fong Chun Formosa Fishery Company, one of the three biggest tuna traders globally and the parent company of American canned tuna and salmon producer Bumble Bee Foods. There are also hundreds of Taiwanese-owned vessels that are flagged to other countries.

Over 20,000 migrant fishers from countries like Indonesia and the Philippines work on Taiwan’s distant water fishing fleet. For years, groups such as Greenpeace have criticised it for perpetrating modern slavery on the high seas.

In a report earlier this year, Greenpeace found that illegal, unreported and undocumented fishing and alleged forced labour continue to happen aboard Taiwanese vessels operating in the Atlantic Ocean.

The Fisheries Agency said that besides fully implementing existing rules, it is now drafting amendments to ban convicted human traffickers from obtaining approval to invest in, or operate any foreign-flag fishing vessel. It also wants to revoke any approvals given to convicted human traffickers.

The Fisheries Agency will consider gradually increasing the salary of foreign crew members deployed overseas, without hurting the competitiveness of the industry, its spokesperson said.

Agency inspectors now conduct interviews with foreign crew members when their vessels arrive at domestic or foreign ports, but the agency will enhance the quality of interviews and interpretation.

Foreign crew members may currently dial a Foreign Workers’ Free Hotline set up by Taiwan’s Ministry of Labour, but in future, there will be policies to encourage or subsidise operators to install wi-fi on board vessels. This will “open up new channels of appeals and communication for foreign crew”, the spokesperson said.

Other plans include establishing a service centre for crew members in the Kaohsiung Qianzhen Fishing Port.

The agency urged non-governmental organisations to provide “tangible evidence” when making allegations, and said it would keep communicating with US counterparts on this issue.