ExxonMobil wants to build a network of carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) facilities around Southeast Asia, so that the regional bloc can continue to grow its economies while addressing climate change, a senior executive at the energy major said on Monday.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Speaking at Singapore Interational Energy Week, Joe Blommaert, an Exxon lifer who was appointed to run a newly created low-carbon solutions unit in February, said that Exxon was aiming to create a series of CCUS hubs at key heavy-emitting industrial sites around the region to absorb emissions at source.

Carbon capture technology sucks up carbon dioxide before it can be released into the atmosphere, then stores it underground or reuses it to create new products such as concrete, fertiliser, and fuel.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the technology will be needed to limit global temperatures to within safe levels, although doubt surrounds its viability because the technology is expensive and hard to scale. CCS is not yet at the commercialisation stage and its critics charge that it will prolong the use of polluting fossil fuels.

Blommaert said that Exxon has captured and stored more man-made carbon dioxide than any company, and aimed to deploy in Asia a similar model proposed for the United States, where the company is planning to spend US$100 billion on burying 100 million tonnes a year of carbon under the Gulf of Mexico.

“

ExxonMobil wants to do its part, must do its part, and will do its part [to combat climate change].

Joe Blommaert, president, low carbon solutions, ExxonMobil

One planned carbon capture site would be Singapore, which is home to Exxon’s largest petrochemicals refinery globally. Since there are no suitable storage sites in the city-state, the captured carbon could be exported to suitable sites in neighbouring countries, he said. The idea is to create a network for connecting high-emitting industry to carbon storage sites around the region.

“This network could have significant impact on regional emissions and be a model for other parts of world,” said Blommaert, who noted that Southeast Asia’s industrial carbon emissions exceed four billion tonnes per year. Heavy industries such as cement production, iron and steel manufacturing and chemicals account for almost one-fifth of the regional bloc’s energy-related emissions.

“It would enable Southeast Asia to continue along its economic development path to provide affordable energy and products that support modern life, while also addressing climate change concerns,” he said. Earlier in his speech, Blommaert said the demand for energy-intensive products that provide “the tools of modern living” — from buildings and roads to the casing and inerds of a mobile phone — would continue to grow as the global population is expected to hit nine billion by 2050.

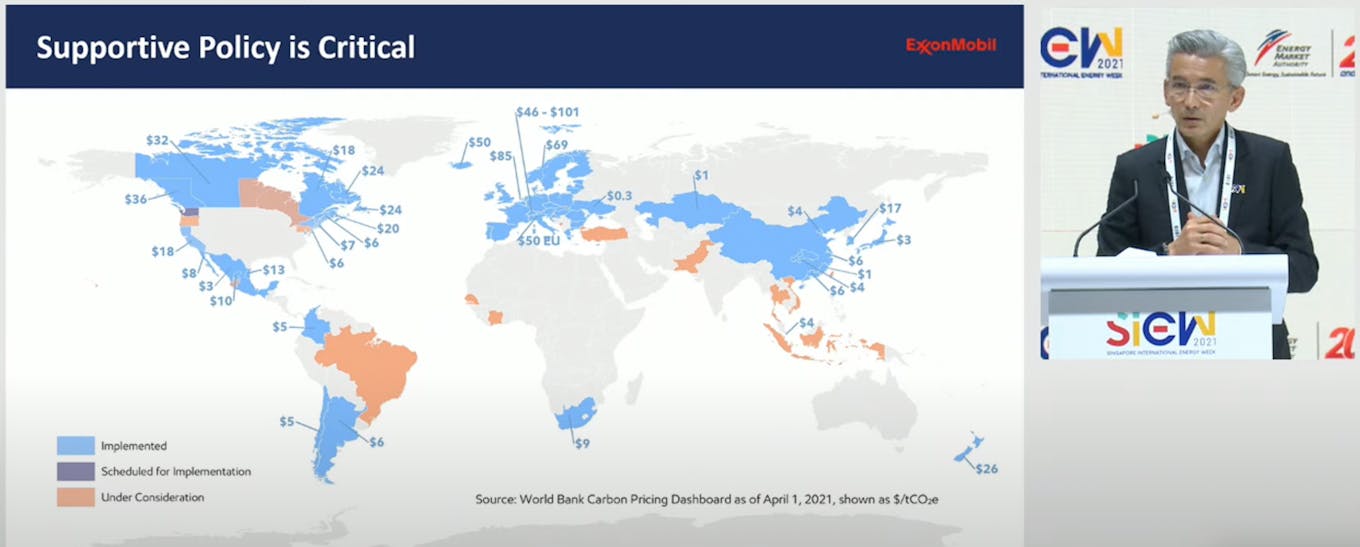

To make the carbon capture network idea work, the region’s governments would need to set a transparent price on carbon to trade it across borders, Blommaert said. He cautioned that globally the carbon price varies significantly. “ExxonMobil supports harmonising [carbon trading] systems across country borders,” he said.

Blommaert said the region’s governments needed to set a “transparent” price on carbon. He displayed a slide that showed World Bank data on the varying price of carbon around the world [click to enlarge]. Image: SIEW

Meeting the Paris Agreement’s climate goals would be “virtually impossible” without Southeast Asia deploying CCUS, an International Energy Agency analyst said recently — but the technology is controversial. Critics say heavy-emitters like Exxon are relying on CCUS to enable them to continue polluting and avoid making the steep carbon reductions necessary to align with the Paris Agreement on climate change.

There are also questions about the technology’s effectiveness. A 2019 study by Stanford University found that the carbon capture technology used in a coal power station only slashed emissions by about 10 per cent, while Exxon rival Chevron recently conceded that “technical challenges” were hampering the CCUS facility at its liquefied natural gas plant in Western Australia.

Exxon has long resisted calls to take action to reduce its emissions, but shareholder pressure has prompted the company — which lost US$22 billion last year amid a global energy slump — to change its tune. The firm disclosed its emissions for the first time in January, revealing that it emits the equivalent of 730 million tonnes of carbon a year.

The company has yet to follow rivals such as Royal Dutch Shell, China’s Sinopec, and American firm, Occidental Petroleum and set targets to reduce its emissions. But Blommaert said that Exxon acknowledged the importance of the Paris Agreement, which has set out to cap global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius. “ExxonMobil wants to do its part, must do its part, and will do its part,” he said.