While major credit rating agencies now provide detailed environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores to bond investors, these scores do not directly influence credit ratings, a new study from the climate and energy think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) reveals.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In recent years, rating agencies have developed ESG credit scores to better integrate ESG-related risks into the assessment of an entity’s creditworthiness. But in an analysis of more than 700 corporates, IEEFA found that the introduction of this “ESG-enhanced credit rating methodology”, has not resulted in any significant rating changes globally across all sectors.

“Presently, there is no readily available way for bond investors to assess long-term credit risks. ESG credit scores simply provide a rough gauge as to how exposed a company is to ESG risks,” Hazel Ilango, an energy finance analyst at IEEFA who authored of the report, told Eco-Business.

“A company can have a weak ESG credit score, be carbon intensive or lack a clear carbon transition pathway, and yet be assigned a high investment grade rating due to its high ability to repay its debt in the next three to five years,” said Ilango.

A bond is deemed “investment grade” if its credit rating is at least “BBB-“, meaning rating providers believe the corporate or government debt is very likely to be paid back with interest. These ratings play a critical role in determining how much entities seeking to borrow money must pay to access credit markets. The higher the credit rating, the lower the cost of debt and the easier it is for issuers to obtain funding.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that around 70 per cent of clean energy investments need to be carried out over the next decade to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. Given the substantial upfront costs of investing in clean energy assets like wind and solar, widespread access to low-cost debt will be pivotal for the clean energy transition.

However “as it stands, the current credit rating methodology is a disadvantage for companies that are pursuing a sustainable transition,” observed Ilango.

This is made clear in Ilango’s comparison of state-owned power producer China Huaneng Group Corp (Huaneng) to the Danish offshore wind power developer Orsted in the report. The credit ratings of both companies are supported by their affiliation with their respective government entities. They also share similar social and governance scores from rating providers.

What differs is the environmental risks of the companies. In 2022, Huaneng was assigned a negative overall ESG credit score by S&P and Moody’s due to the significant coal-fired installed capacity in its generation mix, which makes it highly vulnerable to stranded asset risks. Meanwhile, Orsted got a more positive environmental score from the rating agencies given its heavy concentration in renewable power generation.

Despite the explicit environmental risks Huaneng was exposed to, it maintained an “A” credit rating across all three agencies. In contrast, Orsted, which rapidly decarbonised its business model over the last decade to transform itself from a dominant player in coal-fired power generation to the world’s largest offshore wind power developer, maintained its credit rating in the “BBB” range from these agencies.

This comparison underscores how high-emitting companies like Huaneng “continue to benefit unfairly from low borrowing costs and increased demand in the debt capital market”, said Illango. This runs contrary to IEA’s recommendation to enhance access to low-cost financing for the clean energy transition, since companies like Orsted are not recognised for their proactive efforts to transition to a more sustainable business model.

“Credit rating agencies are not oblivious to material ESG risks or climate change impacts as they have clearly outlined in several public reports,” observed Ilango. But these impacts only become material to an entity’s creditworthiness when they become “real” – that is, sufficiently certain, quantifiable, and foreseeable.

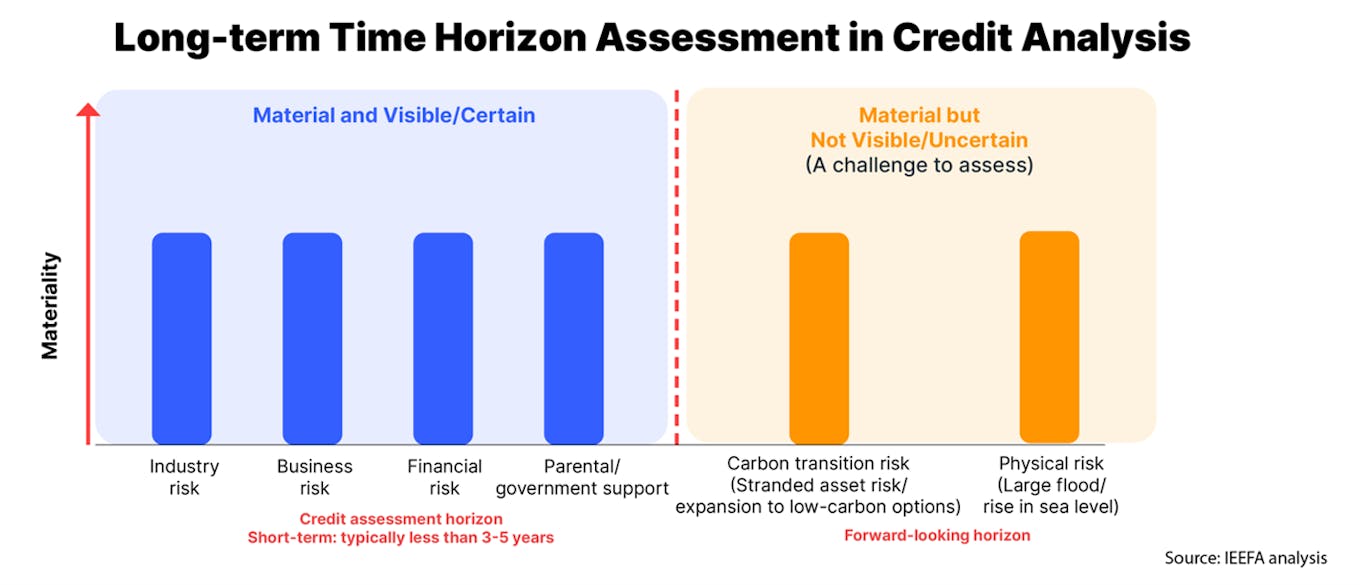

Climate-related risks - like more frequent and severe floods, storms, and wildfires - are expected to intensify in the longer term but have no effect on credit assessments as they are considered uncertain forward-looking risks, compared to carbon taxes which are visible in the short-term horizon. Image: IEEFA

“It could be too late to consider these risks, particularly climate change-related threats, only when they become visible and certain — while we sit and wait on a snowballing crisis,” Ilango contended.

For instance, California’s Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), a large regulated electric and gas utility, filed for what is widely regarded as the first “climate bankruptcy” in 2019, after S&P and Moody’s downgraded its credit rating due to the over US$30 billion in liabilities related to a series of wildfires between 2015 and 2018.

“This highlights how what is currently deemed uncertain risk could result in a multi-notch downgrade and, ultimately, bankruptcy, which can have a severe impact on bondholders,” said Ilango.

“

The current credit rating model is short-sighted and not intuitive enough to provide an early warning signal ahead of a climate-related crisis.

Hazel Ilango, energy finance analyst, IEEFA

This is not the first time the credit rating system has faced a reckoning from external shocks.

Credit rating agencies came under heavy scrutiny following the 2007 financial crisis as they were believed to have provided overly positive ratings on mortgage-backed securities, which misled investors to believe their investments carried little to no risk, contributing to the subsequent subprime mortgage collapse.

IEEFA’s analysis warns that without integrating ESG risks into rating methodologies, investors seeking long-term opportunities – which includes investors who do not focus on ESG themes – would not be aware of their exposure to downside risks.

Overhauling the credit rating model

Ilango gives credit to rating agencies for their efforts to integrate the long-term risks associated with fossil fuel-related sectors into their credit ratings in recent years.

In 2021, S&P Global issued a rating upgrade for Taiwan-based Formosa due to delays in its planned Louisiana plastic and petrochemical complex, which had faced years of strong opposition from local residents. The rating agency even implied that cancelling the project would be better than laying out significant cash for a high-risk investment.

But credit rating agencies still have a long way to go, Ilango said. “The conventional rating methodology requires an overhaul to include long-term risk and produce a tangible outcome on credit rating due to ESG factors.”

Acknowledging that a “complete overhaul” would require time and effort, Ilango proposed a few measures that could be readily incorporated into the existing rating system.

One approach is to include a standalone ESG risks assessment in the current rating system, which European rating agency Scope Ratings has done for its sovereign credit rating methodology. Scope gives ESG factors a 25 per cent weighting, highlighting longer-run ESG risks in their rating model.

Another approach is a double rating model, which could provide the market with an ESG credit-adjusted rating, in addition to conventional ratings of the same issuer.

For instance, a company with a “BBB” rating based on the conventional credit assessment could subsequently receive an upgrade to “A” if it has a substantial decarbonisation strategy and strong social and governance performance.

In addition to the two proposed models, rating agencies can use scenario analysis as a transitional measure to lay out long-term trends and risk trajectories of issuers.

For example, a power company located on a coast might be assigned a healthy “AA” credit rating. Using a scenario analysis model, rating agencies could estimate how likely a flood that damages a varying proportion of the company’s facilities could lead to a change in credit rating. So if a flood damages 75 per cent of the company’s facilities, the rating could be downgraded to “BB” – which could remain unchanged if only 20 per cent of its facilities get damaged.

Beyond adopting new models, Ilango believes regulators, investors, climate risk experts, and rating agencies need to come to a consensus on what constitutes a “long-term horizon”.

“What is considered long term? 10 years, 15 years, 30 years? Only after a long-term time frame has been established can agreement on material ESG factors and credit assessment be centred on it.”

“This is consistent with the World Bank findings where some investors would prefer the credit rating agencies to extend their ESG output by including longer time horizons for ratings,” she added.