The largest coffee companies in the world including Nestle, Starbucks, Lavazza and UCC are failing to report transparently on their sustainability commitments and are doing too little to improve the livelihoods of farmers and conserve nature, a new report has found.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

While large companies made billions of dollars from coffee consumption, coffee farmers faced dire straits in 2020. More of them were pushed below the extreme poverty line of surviving on US$1.90 a day as coffee prices remained up to 30 per cent below the 10-year average for most of last year. The proportion of coffee farmers living below the poverty line in Nicaragua increased by up to half, for instance. This meant that coffee production was not economically viable for the majority of coffee farmers worldwide, said a group of sustainability organisations called the Coffee Collective in the latest Coffee Barometer report.

“The coffee sector’s extractive model of production—relying on rural poverty, devalorised work and the depletion of natural resources—denies that a price has to be paid for labour and land use at origin,” the collective declared.

This is in stark contrast to the billions of dollars made by coffee companies, which are highly concentrated in the United States and Europe, said Conservation International, a collective member along with Hivos, Oxfam Belgium and Solidaridad, in a media release on Thursday (14 January).

Why are coffee farmers earning so little?

Multiple factors affect farmers’ profits. These include farm size, currency exchange rates, labour costs, market access, coffee plant diseases, fertiliser costs, and lack of access to capital and insurance, according to the Coffee Barometer report.

Due to many reasons — low volumes, poor market information, lack of infrastructure — producers are largely price takers. Farmers’ revenue also depends on operating costs, which often outpace inflation and the exchange rate of their local currency versus the US dollar.

Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia and Indonesia are some of the main coffee producers.

Coffee is grown on approximately 12.5 million farms worldwide. Almost all of the farms, or 95 per cent, are smaller than five hectares (about seven football pitches). About 84 per cent are smaller than two hectares. These smallholder farms produce up to 73 per cent of the world’s coffee.

The Coffee Barometer 2020 report shone the spotlight on 10 of the world’s largest coffee roasters and five of the largest traders. The top 10 roasters—led by Nestle, Starbucks and JDE Peets—roasted 35 per cent of the world’s coffee and generated an estimated US$55 billion in total revenue in 2019, according to the report.

The top five traders were Neumann Kaffee Gruppe, Louis Dreyfus Company, ECOM, ED&F Man, and Olam. They handled half the total unroasted coffee export production in 2019, which amounted to 62.5 million bags.

Voluntary schemes not going far enough

Transparency is still lacking across production, trade, and consumption, the report found.

While some companies have comprehensive policies in place, many large traders and roasters remain unclear on their commitments and any progress made, said Conservation International. Many lack a comprehensive sustainability strategy with measurable targets over time. “No one is doing enough,” it said.

“Big coffee companies need to actually prove their supply chains are free from human rights violations and deforestation, and that they are investing in higher farmer income, better labour standards, and climate change adaptation. Policies are not enough; if you want us to believe you’re doing good, you have to show it,” said Stefaan Calmeyn, Oxfam Belgium’s coffee programme manager.

Current schemes to improve sustainability are limited in effect, the report found. Voluntary sustainability standards, such as Fairtrade and 4C, are not enough to improve incomes of smallholder farmers, who produce an estimated 73 per cent of the world’s coffee.

Three-quarters of certified coffee is sold as conventional coffee as the voluntary schemes are unable to manage the supply of certified coffee. This hurts the profits of certified producers who have had to pay upfront costs for certification. It reduces their financial ability and motivation to invest in better farming practices, the report found.

“

The coffee sector’s extractive model of production—relying on rural poverty, devalorised work and the depletion of natural resources—denies that a price has to be paid for labour and land use at origin.

Coffee Barometer 2020 report

If farmers are unable to invest in their farm or make production more sustainable, they will be unable to adapt to climate change, the report argued. Besides rising temperatures, droughts and hurricanes, farmers also face the worsening of coffee-specific pests and diseases, such as the “La Roya” fungus or the coffee berry borer, a highly harmful beetle.

Decreasing farm revenues and rising costs put smallholder livelihoods under threat, it said.

How can companies step up?

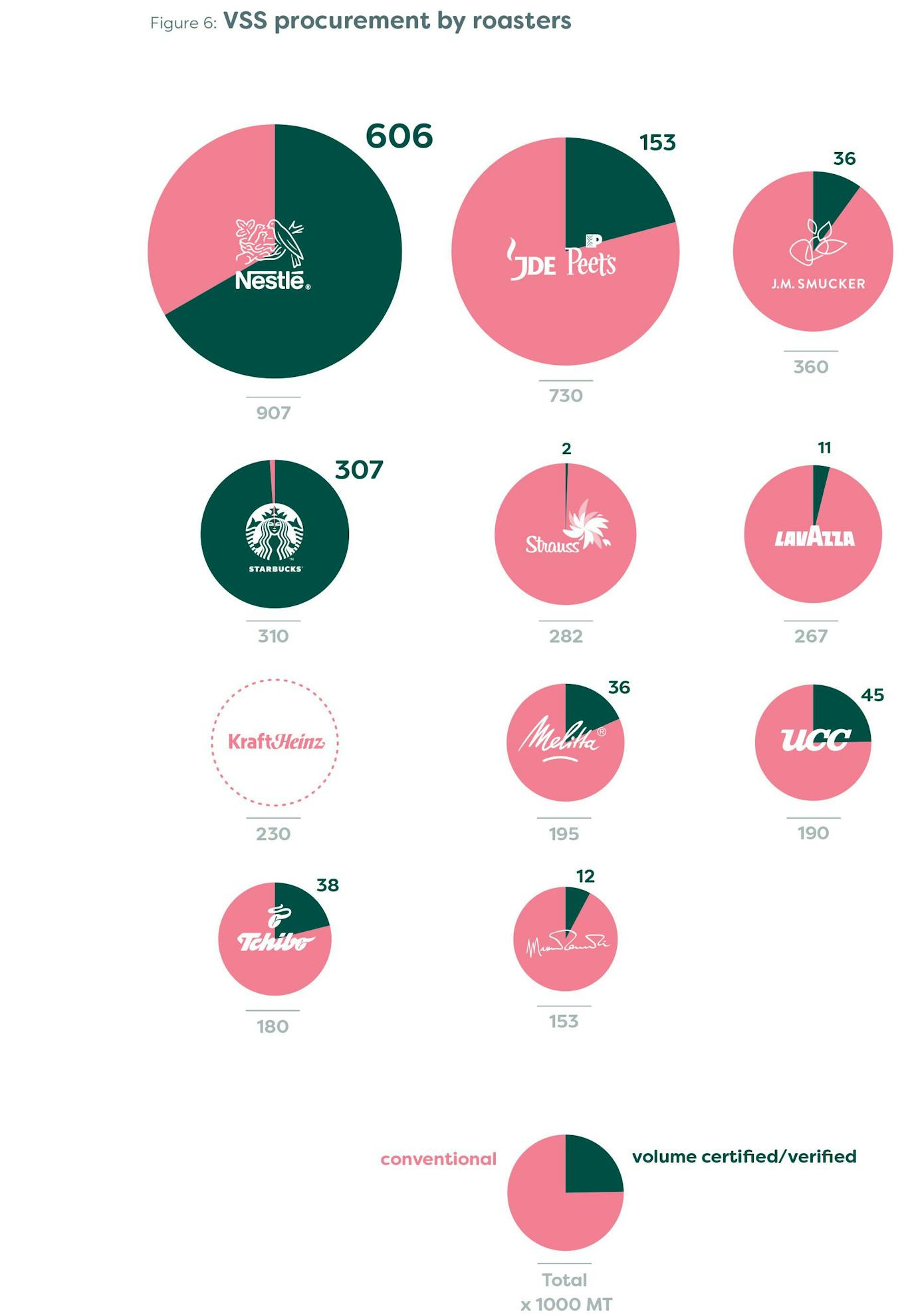

Among the biggest roasters, Starbucks led the way in procurement of certified coffee, followed by Nestle. Only a fraction of the coffee procured by other large roasters such as JDE Peets, JM Smucker and Lavazza was certified sustainable, according to the Coffee Barometer.

The proportion of coffee with sustainable certification procured by 10 major roasters: Nestle, JDE Peets, JM Smucker, Starbucks, Strauss, Lavazza, Kraft Heinz, Melitta, UCC, Tchibo, and Massimo Zanetti. Image: Coffee Barometer 2020

Among the largest coffee traders, Olam has done the most in setting goals related to wellbeing and prosperity of communities, and climate action. Neumann Kaffee Gruppe, Louis Dreyfus Company, ECOM and ED&F Man have not revealed their contributions to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals or set targets, according to the report.

All 15 companies covered in the report are part of at least one multi-stakeholder initiative such as the Global Coffee Platform and World Coffee Research. Such initiatives need “binding commitments, robust mechanisms that confirm progress in the field, and more than shoestring budgets”, in order for more farmers to benefit from the coffee value chain, said Conservation International.

The report noted that solutions will not be the same everywhere, and probably have to comprise a mix of voluntary and mandatory approaches.

Companies will need to prepare for new government policies—particularly in Europe, the world’s largest coffee consuming region—and prove that their supply chains are free of any human rights violations, as well as deforestation, it noted. The United Kingdom, for instance, has proposed a due diligence law on forest risk commodities, and Germany and Switzerland are set to do the same.