It’s been eight years since China’s “war against pollution” began, with its capital Beijing finally emerging victorious last year.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The city’s annual level of PM2.5, fine particles less than 2.5 micrometres in width that penetrate deep into the lungs, fell to 33 micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m₃), meeting the country’s 35μg/m₃ standard for urban areas.

It’s a stark contrast to 2013, when a January winter smog drove air pollution levels up to 993μg/m₃ in parts of Beijing – spurring a clampdown on bad air. The number of days with heavy air pollution, with a minimum PM2.5 reading of 201μg/m₃, dropped from 58 days in 2013 to eight in 2021, according to Chinese authorities.

Improvements are visible across China, as authorities tighten emissions standards, upgrade machinery and help homeowners switch to cleaner fuels for cooking and heating.

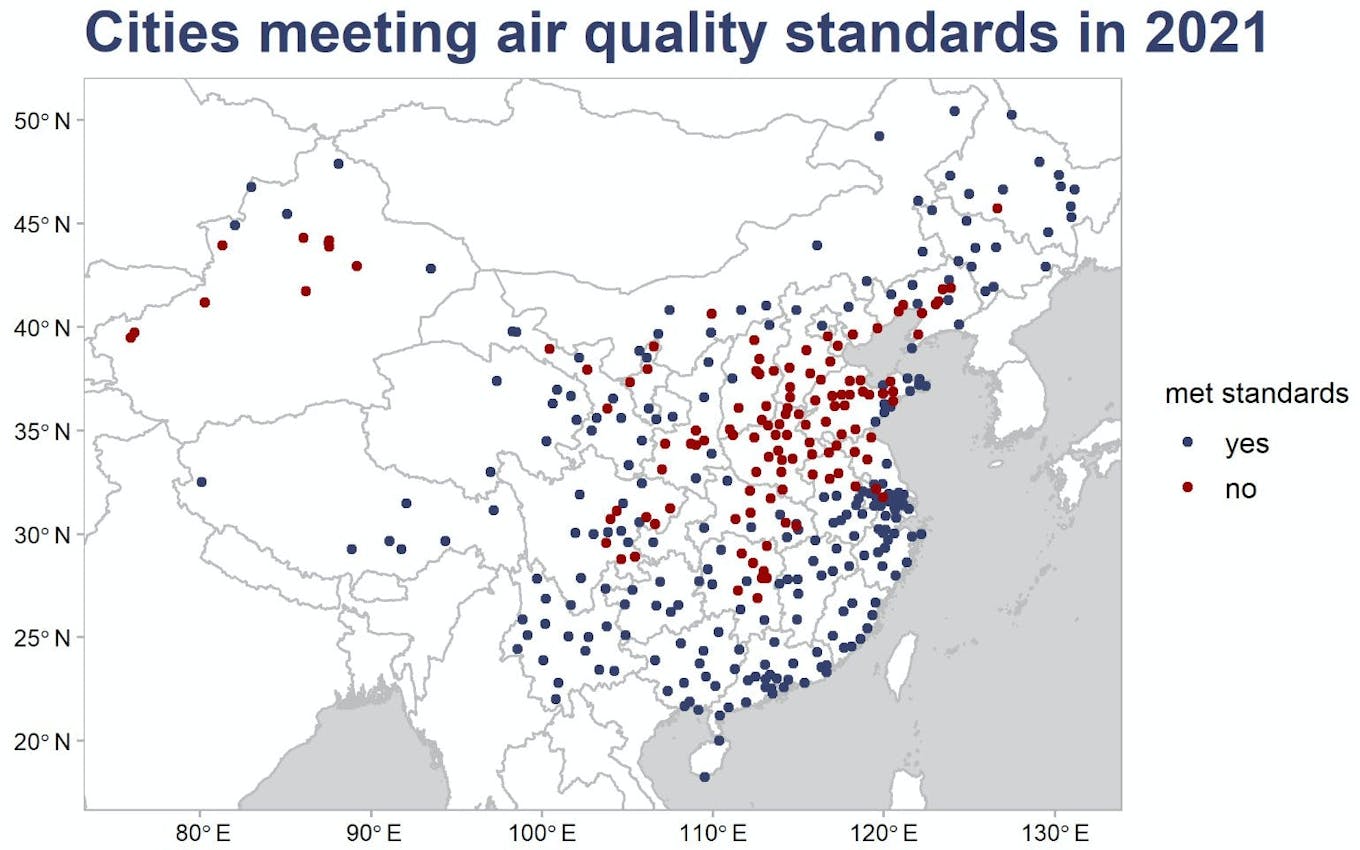

In 2015, 80 per cent of over 360 monitored cities countrywide failed to meet the PM2.5 mark. Last year, the figure dropped to 31 per cent, according to monitoring data provided by research group Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

About 31 per cent of 360 monitored cities across China met PM2.5 standards of 35 μg/m₃ in 2021. Image: CREA

While Beijing passed the mark last year, nearby provinces are still seeing some of the heaviest pollution nationwide.

Experts say it is a problem that may be harder to solve, due to issues such as industrial make-up and the political will to reduce sources of pollution.

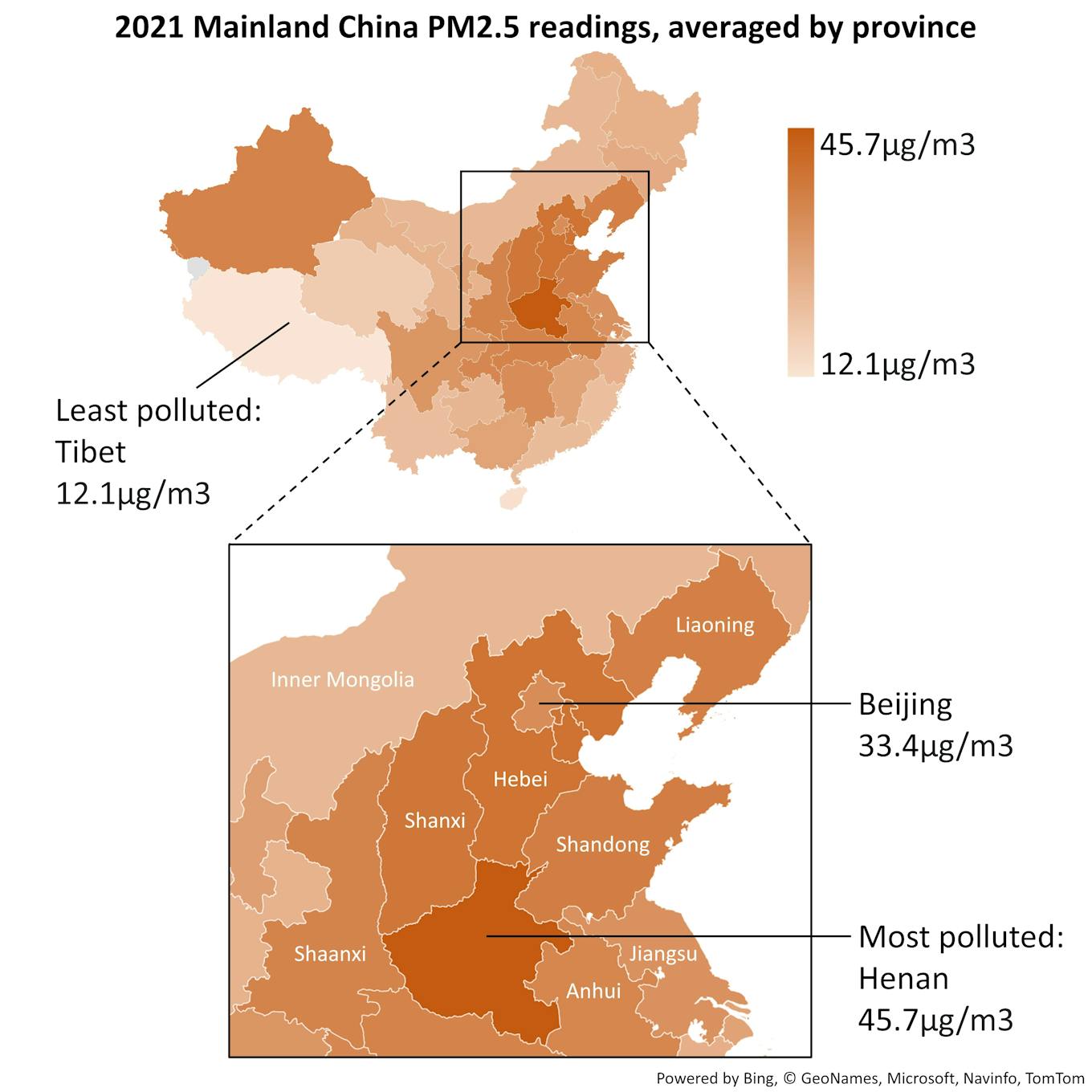

China’s 2021 PM2.5 concentration across provinces, based on data collected by CREA. Readings from days with sandstorms coming from Western China deserts have been omitted.

Industrial hotspots

Based on averaged city-level readings last year, the most polluted province in China last year was Henan, at over 45μg/m₃.

Government office Hong Kong Trade Development Council describes the province as rich in mineral and fossil resources contributing close to 30 per cent of its 2019 revenue. Agriculture, which also causes PM2.5 pollution through manure and fertiliser emissions, formed another 7.5 per cent of its output.

Fossil fuels and mineral products represented just 8 per cent of Beijing’s industrial output last year.

Beijing is partly encircled by Hebei province, where chemicals, metals and fossil fuels make up more than half of its revenue. The province averaged 39.5μg/m₃ of PM2.5 last year.

In 2015, China said it would move industrial activity from Beijing to Hebei, as part of a regional economic plan. But Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at CREA, said that this move had started even before 2008, the year Beijing hosted the Olympic games.

“Those industries ballooned in scale in the subsequent years,” he said, explaining the higher air pollution.

“The next steps will involve switching from fossil fuels to clean energy, as the benefits from better filters and scrubbers have largely been realised,” he added, referring to devices factories use to reduce pollutants from smokestack emissions.

National attention on tackling poor air quality in the heavily polluted areas has also increased. In 2018, the central government designated the Fenwei Plain, comprising Henan and two neighbouring industrial provinces Shanxi and Shaanxi, a new focus area for combating poor air quality.

“From 2013 to 2017, 12 cities within this area performed very poorly,” explained Liu Qian, Greenpeace East Asia’s air pollution project lead. “About half of the 20 cities with the worst air pollution came from the Fenwei Plain.”

These areas have switched from coal to natural gas, a less pollutive fossil fuel, for winter heating. Steel and coke industries, which are hugely fossil fuel intensive, have been asked to consolidate to weed out smaller, inefficient players, and curtail production when air pollution gets bad.

As a result, PM2.5 levels in the region dropped between 6 to 14 per cent on-year, according to local news reports and data from Greenpeace East Asia. Shanxi and Shaanxi had average PM2.5 readings of 41.60μg/m₃ and 42μg/m₃.

“If the changes in the next five years can keep up with this pace of change, they definitely can hit the target,” said Liu.

China’s state planner said in October that energy-intensive sectors like steel, aluminium, cement and oil refining should ensure that more than 30 per cent of their production capacity meets tighter energy efficiency standards by 2025.

But efforts could be sabotaged by increased coal activity in these regions. Shanxi was told to increase coal output late last year amid an energy crunch driven by coal supply shortages and strong demand from manufacturers. Meanwhile, new coal power plants have been approved in Shaanxi and several southern and western provinces. China is aiming to peak coal use in 2025.

“It is going to be a very slow process of spreading that success in Shanghai and Beijing to other provinces for as long as they keep building coal fired power plants,” said Dr Philip Andrews-Speed, a senior principal fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Energy Studies Institute.

Shanghai has also been a key focus area for air pollution reduction efforts since 2013. The financial hub had a PM2.5 reading of 28μg/m₃ last year.

Another PM2.5 hotspot is Xinjiang, an energy and metals hub in China’s far-west, even when sandstorms that affected some cities for over 60 days have been excluded. Its average PM2.5 reading last year was 35.9μg/m₃.

“The province has seen very rapid increases in coal consumption and coal power in the past decade which certainly doesn’t help,” said Myllyvirta.

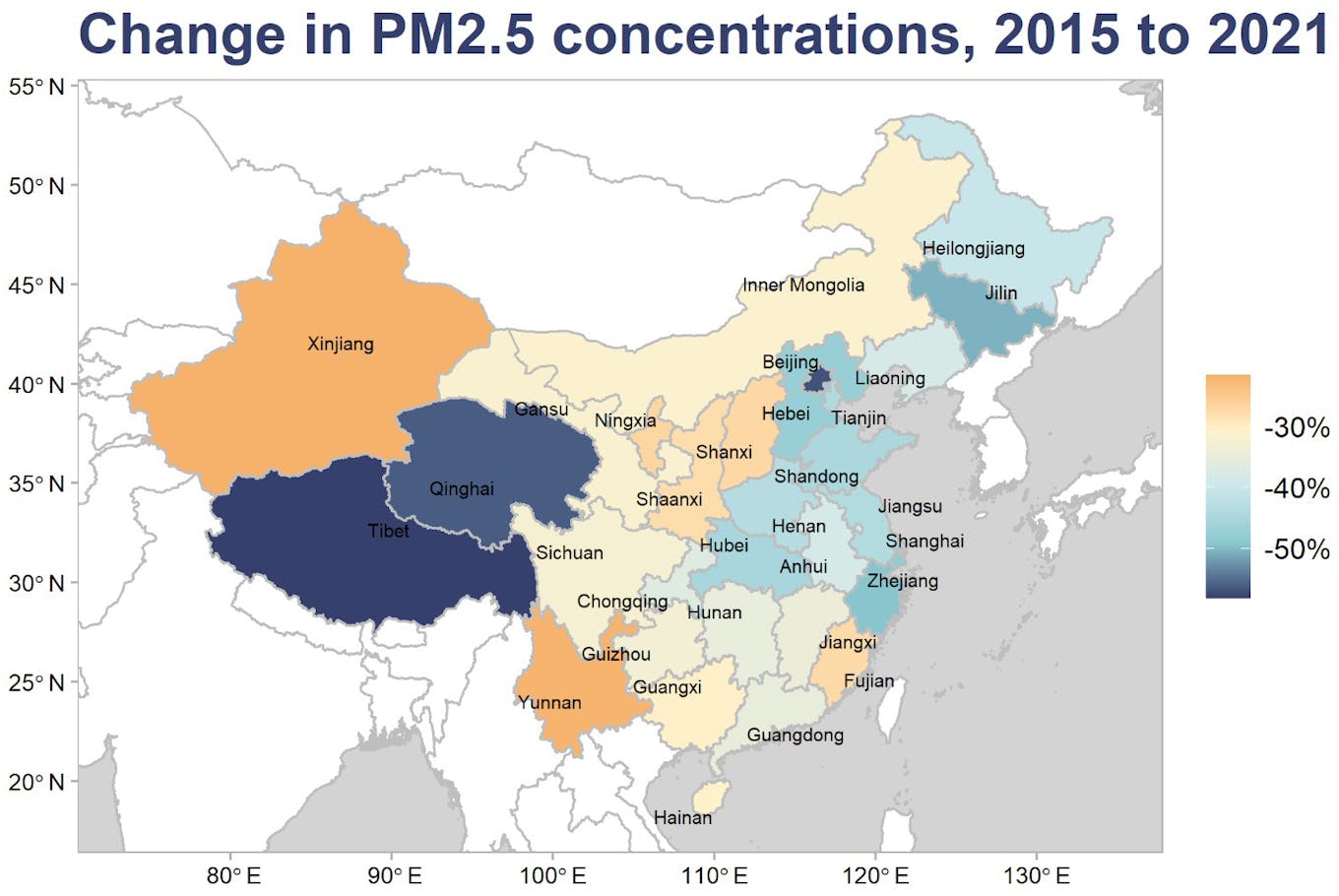

CREA data shows that Xinjiang also has the slowest rate of PM2.5 decrease since 2015, at under 30 per cent, or around half the pace of places like Beijing.

While China’s overall PM2.5 levels have fallen over the years, the gains are unevenly felt across provinces. Image: CREA.

These heavily polluting regions are unlikely to succeed by copying Beijing’s tactics. While most of the PM2.5 across China comes from burning coal, Beijing’s biggest culprit has been vehicle emissions, explained Liu.

Therefore, the capital’s steps of switching to cleaner petrol standards four years ahead of the country, and its world-leading pace in adopting electric vehicles, may not work well in more industrial provinces.

While Beijing is expected to make strides by switching from coal to electric heating in winter, the results of such a switch may not be as significant in other provinces dominated by steel and coal industries, which emit much higher levels of PM2.5.

“Nonetheless, Beijing can be used as a role model in implementing case-by-case measures targeting the pollutants,” Liu added. “The industrial and energy transition – both need to happen.”

Myllyvirta added that Beijing needs further air quality improvements, as it is still above the World Health Organisation’s PM2.5 threshold of 5μg/m₃. In research published by air purifier firm Smart Air, only 16 out of 540 major cities worldwide hit that mark in 2021. None of them were in Asia.

Enforcement strength

“Beijing’s air quality improvements have been huge. Undeniably, part of the reason is strong enforcement measures,” Liu said.

Dr Andrews-Speed thinks strong enforcement comes from the close proximity to national authorities.

“You’ve got the Beijing city government right next door, as it were, to the central government,” he said, adding that political momentum to improve the capital’s air quality was in part generated when the United States embassy in 2008 started broadcasting PM2.5 readings of Beijing and a few key Chinese cities.

After Beijing won the bid to host next month’s winter Olympics in 2015, China president Xi Jinping promised to run a “green” Games. Heavy vehicles have been ordered off the road, mirroring stringent traffic rules ahead of the 2008 Beijing summer Games.

While air quality deteriorated in Beijing in the years after the 2008 Games, Associate Professor Steve Yim, principal investigator at the Earth Observatory of Singapore in Nanyang Technological University, expects the city’s air quality to remain at current levels in the coming years.

“In 2008, the ambient pollution concentration level was far higher,” he said, explaining why the stop-gap measures worked. “The situation now is different as the ambient pollutant concentration level has already reduced substantially.”

There have been gaps in enforcement in other regions. Research by CREA found that while neighbouring Hebei province had been told by the national environment ministry to cut steel production, output has been rising between 2015 and 2020 to beyond the reported capacity of the plants. The report suggested there was “creative accounting” of steel capacity.

Last year, authorities uncovered millions of tonnes worth of illegal oil and coke processing facilities in Shandong. Liu added that some low-grade steel manufacturing facilities were also illegally operating there.

Ground-level ozone

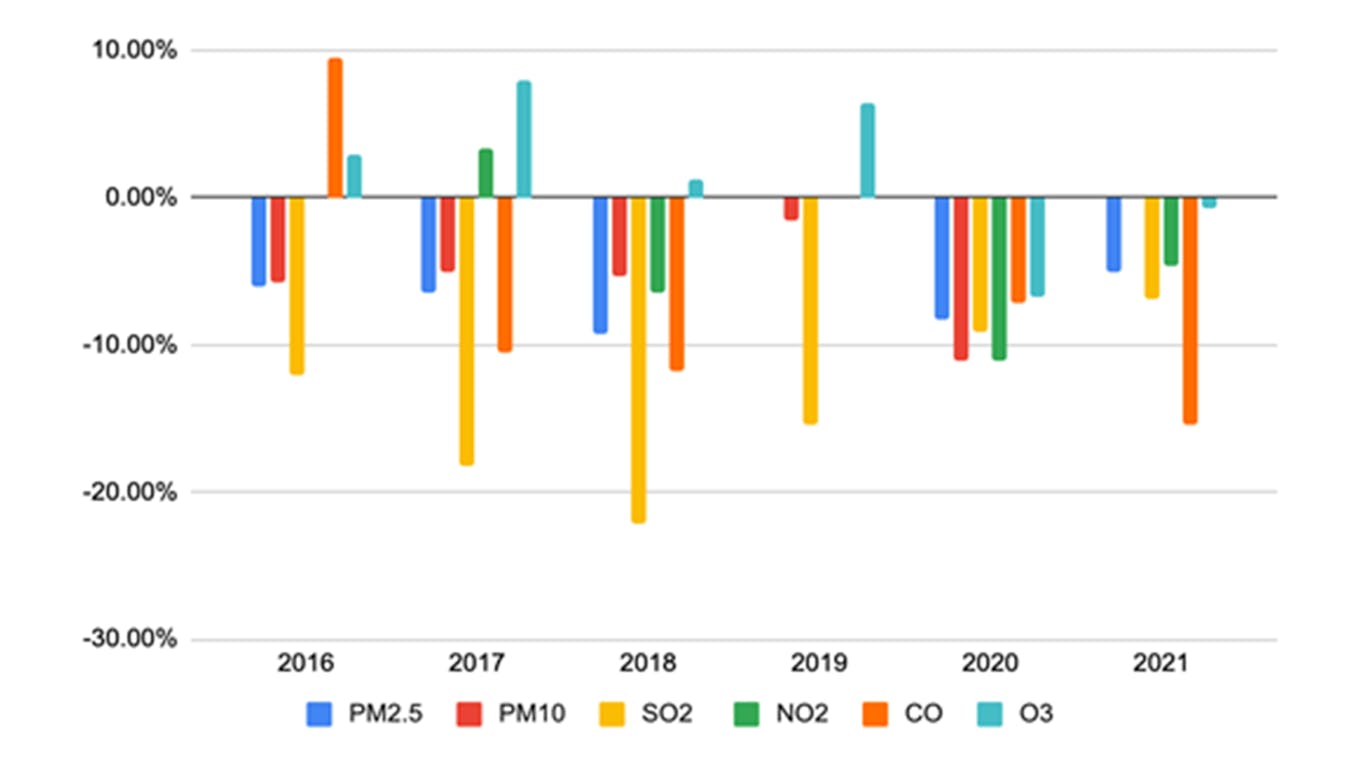

Liu said another pollutant of concern in China is ground-level ozone, which isn’t falling as quickly as other monitored substances.

Apart from ozone and PM2.5, China also monitors ambient levels of PM10, a bigger particulate matter, as well as sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide.

While ozone helps to deflect harmful rays from the sun high in Earth’s atmosphere, ground ozone is a pollutant that can cause heart and lung illnesses.

Changes in concentration for six key air pollutants monitored in China, 2016-2021. Ground ozone increased from 2016 to 2019, and dropped by the lowest percentage points in 2020 and 2021. Image: Greenpeace.

Liu explained that ground ozone was a harder pollutant to control, given its key ingredients, nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds, come from a variety of sources.

Research has also found that reducing other pollutants in the air could also have led to higher ground ozone levels.

“Previous efforts in China was mainly on controlling PM2.5, while ozone was overlooked,” said Yim. “Our research shows that ozone pollution may become critical in the coming few years.”

In a recently published paper, Yim and a team of scientists found that ground level ozone in China will rise in the coming years in every future emissions scenario they tested.

China’s latest 14th Five-Year Plan, its top-level development directive from 2021 to 2025, called for a 10 per cent reduction in emissions of volatile organic compounds, in a bid to manage ozone levels.

Liu said it took till 2021 to tackle such pollution because of the level of expertise needed.

“The target is just a hard figure now. We need to find ways to really achieve it,” she said.