From printing organs to aircraft parts, 3D printing has the potential to revolutionise industries and change the way the world consumes its limited resources.

This is why it is important for Singapore to “stay ahead of the pack” by investing in scientific research and developing new patents in this industry, says Dr Chua Chee Kai, head of the Singapore Centre for 3D Printing (SC3DP) at Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

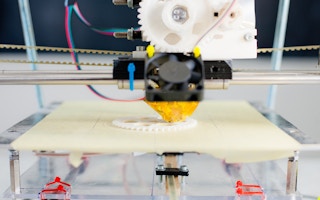

Additive manufacturing (AM), more commonly known as 3D printing, refers to technology that allows digital designs to be built into three-dimensional objects using machines that make the product layer by layer.

United States consulting firm, Wohlers Associates, estimates that the industry could be worth US$10.8 billion by 2020 – up from US$2.2 billion in 2012.

To tap into this growing billion-dollar industry, the SC3DP was set up last December with S$113 million in funding from Singapore’s National Research Foundation and NTU, along with industry partners such as ST Engineering, Keppel Corporation, and Sembcorp Industries.

It is an expansion of the $30 million NTU Additive Manufacturing centre that opened last July, which will now be subsumed into the SC3DP.

Speaking to Singapore Business News at the Inside 3D Printing Conference and Expo at Suntec City held on 27 - 28 January, Prof Chua says the centre will focus on developing four industries which are “of great importance to Singapore”: aerospace and defence, building and construction, marine and offshore, and manufacturing.

3D printing’s myriad applications

_medium.jpg?auto=format&dpr=2&fit=max&ixlib=django-1.2.0&q=45&w=340)

Professor Chua Chee Kai, executive director, SIngapore Centre for 3D Printing, poses with a 3D printed dress at the Nanyang Technological University

In each of these sectors, 3D printing opens up many possibilities in making processes more sustainable and resource efficient. Conventional manufacturing methods, where end products are cut out from larger blocks of materials such as sheet metal, can result in a lot of resource wastage, explains the professor.

In contrast, “3D printing is more resource efficient because you only print what you need”.

The fact that 3D printing assembles items by depositing thin layers of material such as plastic or metal also makes it easy to build product structures that are strong yet lightweight.

This technique, which can be achieved by using honeycomb patterns for example, in which materials are deposited in a row of hollow hexagons, could be put to use in industries such as aerospace and defence.

Aircraft bodies made using the honeycomb structures could be up to 50 per cent lighter, which would reduce fuel usage and greenhouse gases, which in turn could lead to lower fares, says Prof Chua. He has been in the field since 1990, and is also a professor in NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering.

Using 3D printing technology can also make it easier and cheaper to repair components of ships and rigs. The centre is currently exploring ways to focus a laser on damaged components such as turbines and simply ‘print’ more metal where it is needed.

Chua also sees great potential for 3D printing in the healthcare industry. For instance, while each hearing aid was handmade by artisans in the past so as to fit a patient’s ear perfectly, virtually all hearing aids are 3D printed today.

In the future, entire lungs, hearts, and kidneys could be 3D printed and used in organ transplants. But this is a vision is likely to be achieved only “beyond 2030”, says Chua.

Challenges for the industry

“

When I first started out in the industry, funding was pretty tough to come by. But now, the government understands the value of investing in this technology.

Chua Chee Kai, executive director, Singapore Centre for 3D Printing

The picture is not all rosy, however. One challenge the industry faces is that not all materials – such as highly flammable magnesium - can be used in printers today. Secondly, only a single ink can be printed at a time.

Thirdly, industrial grade printers are also unable to meet the demand for large parts from sectors such as aerospace, and marine and offshore, observes Prof Chua.

NTU recently signed a $5 million agreement with German 3D printer makers SLM Solutions to set up a joint laboratory where three PhD students, funded by Singapore’s Economic Development Board, will work to develop a system that addresses all three concerns.

The industry also struggles with a regulatory system that does not keep pace with new AM innovations, says Chua.

For example, 3D printed human tissue would make it much quicker for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to test whether drugs are safe for human consumption. But while FDA stipulates that all drugs must go through human trials, bioprinting is not listed as an option. “Regulation is lagging behind,” he says.

Similarly, it would be a disaster if a 3D printed part caused a malfunction in an airplane, he adds. Industries will continue to grapple with safety regulation and quality certification of 3D printed parts.

Still, Singapore is focused on navigating these challenges and putting the country on the global map for 3D printing.

In the coming years, the centre will be focusing on developing what Prof Chua calls the “4Ps” to cement Singapore’s leadership in this industry: PhD students who can conduct specialised research into how various raw materials or ‘inks’ can be used in printers; postdoctoral fellows; professors; and partnerships with companies to apply research to industrial uses.

Currently, the centre boasts 35 faculty members and has close to 100 postgraduate students today. It aims to secure 27 more full-time researchers and 100 more PhD students over the next decade.

The centre also houses industrial grade 3D printing machines that cost between S$800,000 to S$2.5 million each.

“When I first started out in the industry, funding was pretty tough to come by,” recalls Chua. “But now, the government understands the value of investing in this technology.”

Edited by Jessica Cheam and Stanley Tang