The survival of human beings is a history of adapting to and manipulating our environment. This agency, when taken to extremes, can lull us into a false sense of security and an obsession with having complete control over nature. Yet the ongoing California wildfires and last month’s Hurricane Florence and Typhoon Mangkhut are stark reminders that nature is far from tamable. Homo sapiens, a comparably young resident of the planet, is not excused from millions of years of evolution that dictates only the species who adapt and work with—not against—nature will survive.

For the global north, it is easy to lose sight of the gift of adaptability after generations of industrialisation and technological advancement. Many areas in the United States and Europe have had success mitigating flooding or storm surges by building on high ground or having the resources necessary to implement and maintain major infrastructural systems, such as levees, dams, and seawalls. Threats from climate change, however, have begun to increasingly disrupt that sense of engineered security.

In many parts of the developing world, lack of resources and robust engineering interventions have taught many coastal cities to adapt and live with dynamic waters, where culture accepts flooding as the norm. Our planning, landscape, and urban design practice embraces these historical and contemporary approaches to living with water. Here, we share details from two such cultures that have demonstrated remarkable resilience to living with water: the residents of Wuhan, China; and Manila, Philippines.

“

For many cities with riverbanks or coastlines, water shapes their sense of place. Floods and sea-level rise, however, are often not considered a core part of that identity.

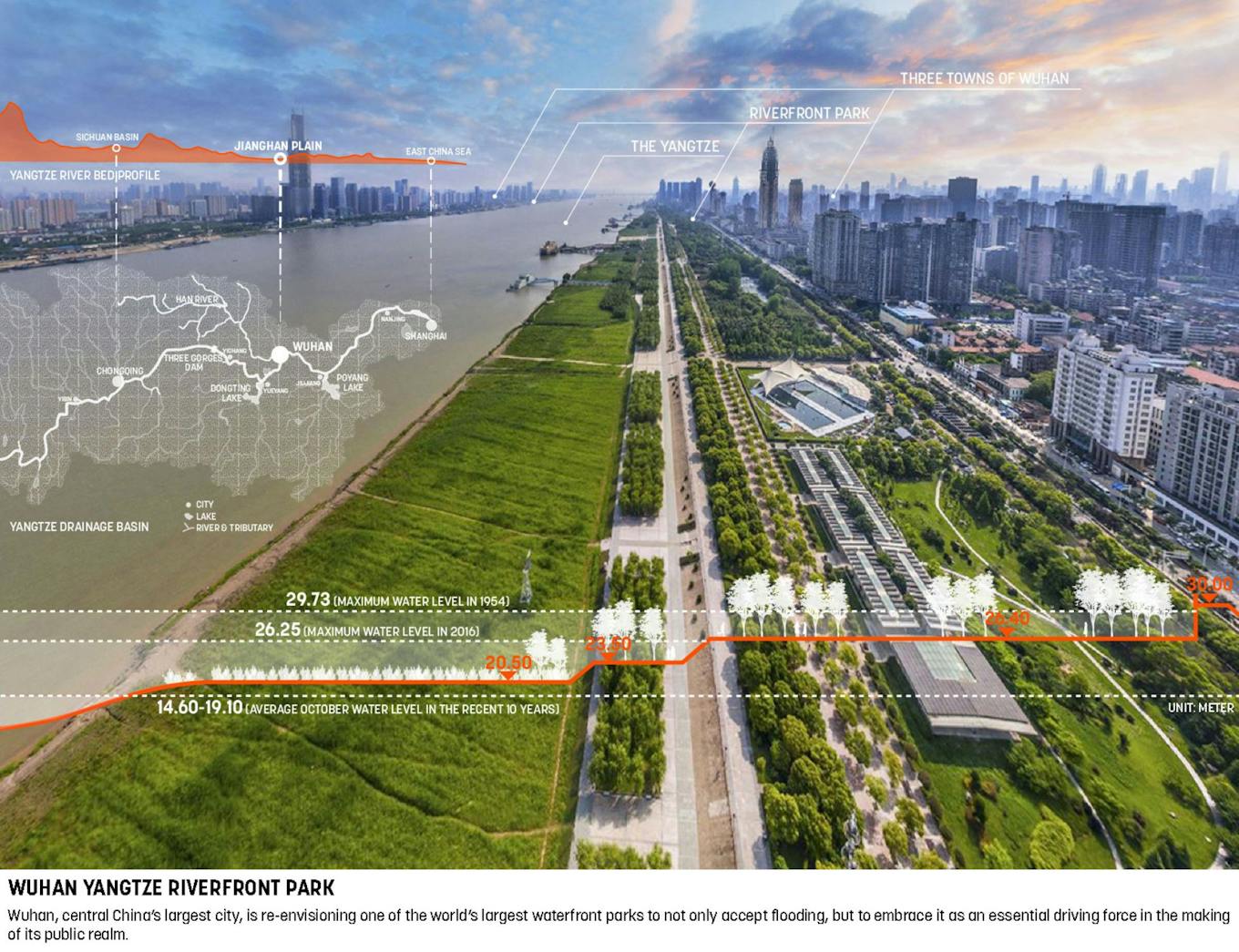

Wuhan, China: A waterfront park forged by flood

Throughout much of China, waterfront properties are at a premium and the conflicts between development and advocacy for open space are acute as land price soars. Wuhan—Central China’s largest city—is uniquely fortunate in this regard, as frequent flooding has unintentionally preserved land for one of the world’s largest riverfront parks. Bisected by the Yangtze River, Wuhan’s age-old wisdom says the floodplain is no safe haven for settlements.

Image: Sasaki

Monsoon-driven surges have been a part of life in this region since it was first settled in the 2nd century, yet floods don’t completely stop the life of the city. On the contrary, it’s not uncommon to see schoolchildren making a game of scrambling across points peeking out from the water; or families enjoying the day by wading or tubing through inundated riverfront parks.

Today, we are developing a master plan for Wuhan’s 10 miles of Yangtze River frontage to nurture a rich regional ecology and to create dynamic recreational experiences attuned to the rising and falling of the Yangtze. The expansive mudflat is restored to provide home for birds, amphibians, fish and other wildlife, while creating a picturesque landscape with evolving seasonal interest.

Repurposing a number of the city’s industrial piers and barges will create one-of-a-kind floating landscapes that allow people to have truly immersive experiences in the Yangtze. Most of the park and its programming along the river are designed to celebrate the spontaneity of the river and incorporate flooding as an essential element of the rich landscape experience. The park transforms into completely different spaces during different seasons and at varying water levels.

A way of life: Protecting Manila’s aquaculture

Another fascinating example of living with water is found in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. As is common with island cultures, water has long been equated with life for Filipinos, whose country is an archipelago comprised of over 7,000 islands and 36,289 km (22,549 miles) of coastline. The nation’s dependence on water is especially apparent for Manila’s informal settlers—urban poor, many of whom live in makeshift dwellings and subsist on ocean fishing and water-borne agriculture.

It is these populations that are most at risk during typhoons—frequent events for this nation on the Pacific Ocean’s “Ring of Fire.” Yet government attempts to relocate some of these settlers are often unsuccessful. What would there be to live on higher ground, if removed from the water—a significant economic resource that Filipinos have relied on for centuries?

A resiliency research initiative, organised by MIT, the World Bank, and Sasaki, sought an answer to the conundrum of how best to protect water-dependent Filipinos who want to stay in place whenever possible.

Known as pilapils, these informal settlers show a remarkable adaptability to water. Image: Dennis Diaz for Sasaki

This research has informed plans for adapted living and managed retreat at several scales—at both coastal and in-land sites. We studied indigenous pilapils, or aquaculture typologies that are native to the area that could be leveraged as sustainable farming solutions for flooded communities.

Additionally, we proposed converting a nearby military base into a semi-permanent “back-up city” for those displaced by natural disasters. Likewise, our master plan for Ananas New Community is piloting sustainable farming structures for in-land communities—whose food supply is easily disrupted during natural disasters.

Translating resiliency: Floodable landscapes and promoting stewardship

Though it might have taken the unique cultures like Wuhan or Manila—for whom high water is more status quo than crisis—to generate these ideas, the general approaches are reproducible elsewhere. Slowly but surely, landscape architects have begun incorporating floodable elements—plantings, paving, and lighting elements—into their project work. This level of attention protects investments in the landscape for the .5 per cent of the year that a site might be flooded, while still delivering a usable community amenity for the other 99.5 per cent of the year.

Indeed, designing floodable landscapes has proven crucial for much of our work in the United States, where many cities bisected by rivers are searching for ways to capitalise on this natural resource while still being prepared for the onslaught of storm surges and record floods.

We designed the Chicago Riverwalk—a below-street level pedestrian haven that was once drab and unused—to withstand being completely submerged. The kicker? Once the water recedes, it only takes city maintenance armed with hoses about eight hours to clean up and reopen the Riverwalk for the public.

The built environment also plays an important part in raising awareness of water—helping create stewards for our most plentiful, and oft-mistreated, natural resource. Cultivating stewardship is top of mind for the Port of Los Angeles, for whom we are designing and building the Wilmington Waterfront Promenade. The promenade reconnects the Wilmington community to the water’s edge—and will promote carefree exploration of the waterfront through a number of design features. Netted sections of the pier’s floor allow for novel, yet safe, interactions with water. Similar to the floating performance barges in Wuhan, we designed floating docks with hammocks built into them to allow residents to experience suspension over water.

Purposefully designed for floods

For many cities with riverbanks or coastlines, water shapes their sense of place. Floods and sea-level rise, however, are often not considered a core part of that identity. As we learn to adapt to increasingly severe flood events, designers are purposefully designing landscapes to withstand flooding while maintaining a community connection to water. To facilitate these connections successfully, we must continue to develop visionary solutions while also studying the age-old approaches of water-based cultures closely.

Only time will tell what impact interventions such as these have on public perception of floods and sea level rise. It is our sincere hope that building landscapes that celebrate our interaction with water will continually remind us of our ability to work with and adapt to nature.

Mary Anne Ocampo is an urban designer and principal with Sasaki whose multidisciplinary training and experience allow her to work across contexts and scales.

Trained as an ecologist and landscape architect, Tao Zhang is active in the arena of ecological design, striving to bridge the gap between practice and science.