In 2017, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the two foremost exporters of food to Qatar, imposed a food blockade on their neighbour. This food blockade led Qatar to fall back on imports from Iran and Turkey. The blockade had longer-term implications for Qatar; by June 1 2018, it had dedicated financial capital to boost its own food production.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Food blockades are not the sole threat to food security. While Singapore diversifies its food sources, the threat of impending food shortages in the region is real, as changing weather patterns, droughts, and monsoon, increase the unpredictability of harvests.

But we don’t have to look as far as Qatar just to imagine a food-secure Singapore. 1960s Singapore just after independence was fully self-sufficient in its food, with jobs on food production that employed residents here and provided fulfilling work.

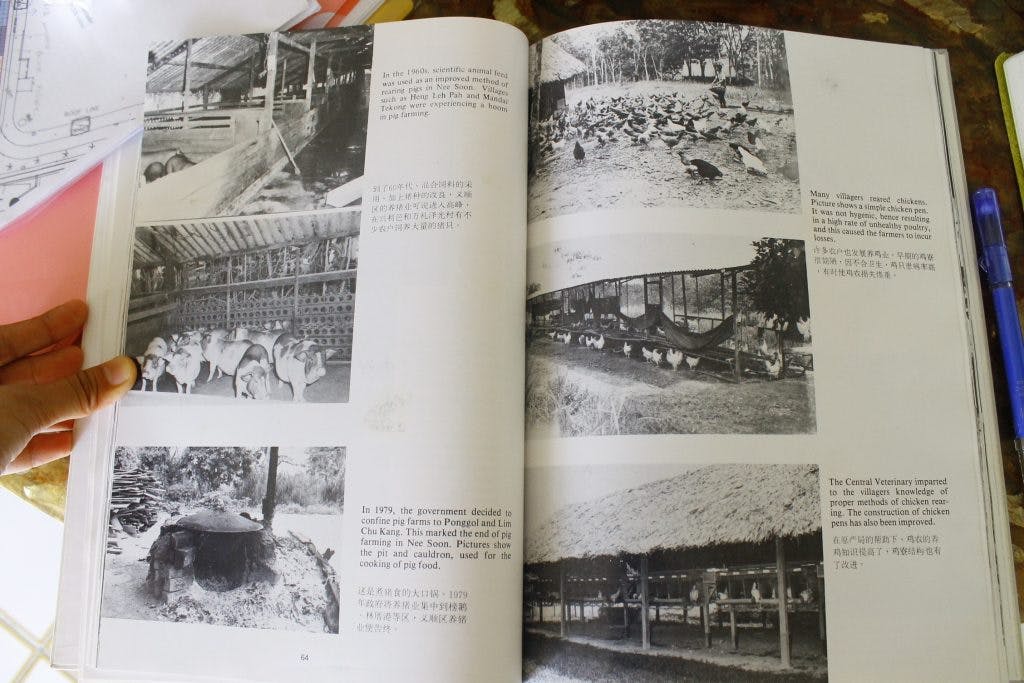

Over nine per cent of the Singaporean population worked on family farms in the early years of independence from the 1960s to 1980s. Their strong attitudes for the nation and independence provided important labour, motivation and energy that made food sufficiency possible. These family farms were the cornerstone of food security in a small vulnerable island state. Not only did they meet 50 per cent of the nation’s vegetable needs and 30 per cent of its fish needs, these small-scale farms were able to practise crop rotation, preserving soil fertility, and mixed farming with animals and food crops. Agricultural production increased despite land limitations, and food products were exported.

Farming in Singapore in the 1960s. In A Pictorial History of Nee Soon, published 1987 in Singapore by The Grassroots Organisations of Nee Soon Constituency.

Understanding the multiple values that family farms brought to the health and stability of Singapore takes some digging, because this story is not well-told. Cynthia Chou’s in-depth research into the end of agriculture in Singapore, some of which we cite here, has a lot to offer us.

We are often led to place more weight on industrial plantations, based on simple comparisons of size. But the acres of small-scale family farms, with their high density, self-ownership, links to family cultivation, and intercropping practices, supported a vast number of social and ecological links, as well as self-employment, healthy communications, mental and physical activity in community with others.

By 1848, there were at least 378 acres of small-scale family-run vegetable farms clustered around the Braddell Road area. In comparison, by the early 1900s, the wealthy Chinese businessman Tan Kah Kee owned 500 acres of land in what is now the Yishun/Sembawang area for pineapple plantations and rubber, opening a pineapple factory in 1905.

In 1931, in spite of limited land, family farmers produced nearly self-sufficient quantities of vegetables for the population. They produced these for the market, existing alongside large capitalist plantations.

The vegetables grown included lettuce, cabbage, onions, parsley, celery, spinach, mint, cucumber, cowpeas, radish, loofah, lady’s finger, brinjal, french beans, bitter gourd, yam, bean, sweet potato, tapioca, groundnut and soya bean.

In March 2019, the Singapore Food Agency (Agri-Food Veterinary Authority at the time) announced plans to increase the production of nutritional needs again to 30% by 2030. In this opinion piece, we highlight the historical link between nutritional needs and social resilience, and the opportunities to connect these in the coming decade.

In particular, we highlight the opportunities presented by stacking multiple uses of land. We focus on the concept of establishing food forests on military land as a viable food security strategy in Singapore and examine one case example of the Green Circle Eco-Farm, as a ready-made future food forest, with proposed guidelines on developing it.

Defence agriculture as functional and innovative use of space

Defence agriculture, as we playfully term it, is not a new narrative in Singapore’s history. “Citizen soldiers who double up as farmers,” as David Boey writes, were already a thing in the 1970s. In 1974, then-Minister of Defence Dr Goh Keng Swee —who took charge of the Primary Production Department a decade after on 6 Jan 1984 — introduced pineapples into Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) camps. The prickly plants provided food, psychological sustenance, and physical defence. Boey, a former defence correspondent for The Straits Times, wrote that 6.5 hectares of military land was transformed into Singapore’s largest pineapple plantation with more than 102,000 Emas Merah and Sarawak pineapple suckers grown by these soldiers. This land has since been re-transformed; it is the land on which the present Institute of Technical Education (ITE) College Central now stands.

Defence agriculture in this example shows that defence places have been included in mixed use (defence & agriculture) approaches to defence land. We argue that such creative use is necessary in a ‘land-scarce’ Singapore.

Stacking multiple values of defence through agroforestry

As our land use policies move with the times, defence is moving into virtual defence, but also climate and environmental defence. Food forests provide, firstly, a landbank of cultivated soil ecosystems for edible food growing. A local food forest also serves as a place for jungle survival training. National Service Forces (NSFs) today go through jungle survival training, which includes a few key lessons: shelter-building, looking for water and food. Food lessons focus on animal-trapping, killing and preparation of food that is required prior to eating. The emphasis is on animals: pythons, chickens, fish. Edible plant identification and knowledge of use is not included. Yet one might easily notice that knowledge of fungi, edible plants, and medicinal herbs are essential to basic survival, especially as climate conditions change and the need to deploy soldiers across various terrain increases.

The idea of stacking multiple uses together also goes hand in hand with the functionality that a food forest provides.

Food forests hold vast differences from conventional industrial agricultural plots. Based on agroforestry principles, the acres of land productivity that can be expected from food forests includes multiple values that go beyond the singular value (product yield) of conventional plots. Cacao companies, such as US-based company Cholaca are looking towards regenerative cacao production, driven by evidence that cacao agroforestry systems have higher returns on labour compared to full-sun monocultures, and as they realise the future survival of the business depends on sustaining the ecosystems that support their producers’ cultivable land. The need for regenerative agriculture is reflected in the new mass of knowledge, technological systems, and new strategic business directions being produced around it and highlights the next step in resilient and sustainable agriculture for the planet.

Case study: Green Circle Eco-Farm

Green Circle Eco-Farm occupies a farm plot in the Lim Chu Kang area in northwest Singapore. Its land lease runs out in December 2021 and next plans for the land are commonly understood to involve the conversion to military land.

Green Circle Eco-Farm has cultivated its land’s biomass over almost 20 years since 1999. Over these 20 years, the build-up of soil structure, soil vitality (a healthy microbial ecosystem) and water retention capacity on its land holds valuable protective functions that can be easily damaged, and lost.

If plans to convert the farm into military land are to proceed, we would urge extra precaution by planners and land developers to ensure that the soil is not removed or damaged during the process, and to carefully consider plans for how the land and soil may be optimally used in the process.

More thought and consideration of national food security, and resilience–the ability to reassemble and regroup in the face of challenge–should be given to the use of scarce natural resources.

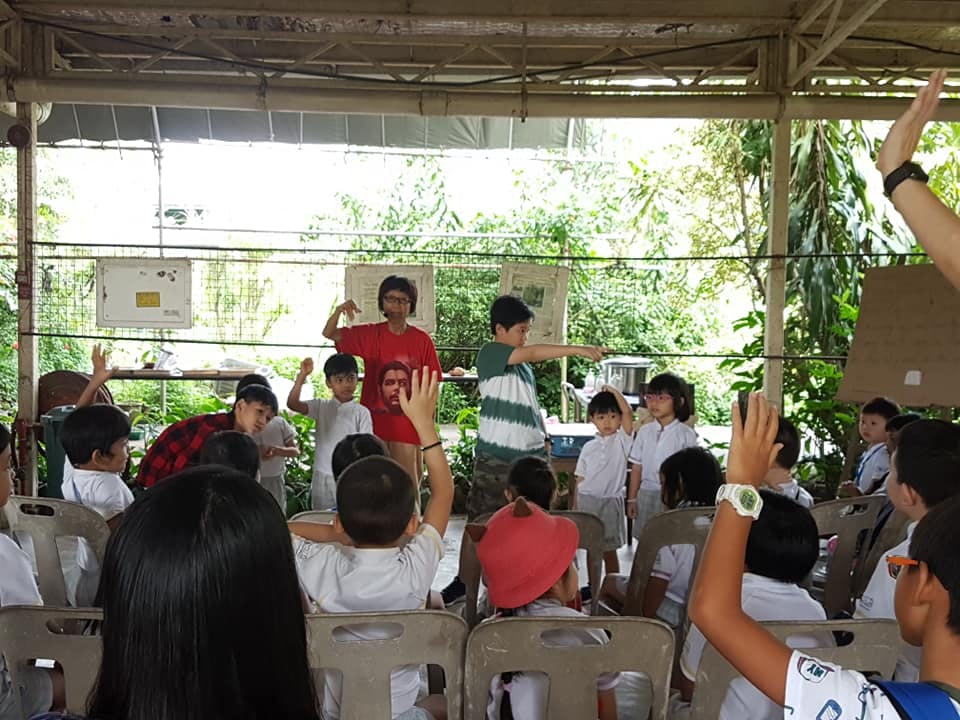

Evelyn Eng from Green Circle Eco-Farm – the farm hosts regular programmes for students – to see, feel, sing and touch the biodiversity that grows when sunlight, knowledge and attention are given to a plot of land. Image: Liow Oi Lian

The Green Circle Eco-Farm holds further potential to be examined as a pilot site for a food forest within defence lands, and how this contributes to public value. And it poses a clear question for us to respond to: as generations ready to inherit the planet, what are we willing to defend of the precious things we have?

This opinion piece was written in 2019. Since then, Evelyn has received a two year extension of the land lease until the end of 2021. She is currently writing another proposal to extend her lease beyond 2021 so that she can continue farming.

Ng Huiying, Woon Tien Wei and Tan Hang Chong are contributors to Foodscape Collective. This story was originally published on Foodscape’s website, Foodscapepages.org.