On 19 August, a pitch was sent to the Eco-Business news desk by Edelman, the world’s largest public relations firm, on behalf of Shell. It was promoting the oil major’s “carbon neutral” car lubricants in Singapore.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

“If you are looking to do features on how one can take a step forward in the mission towards a more sustainable future and lead an eco-friendly lifestyle, we feel that Shell’s carbon neutral Helix Ultra lubricants will be a good addition,” wrote the firm in an email.

A social media post that highlighted the irony of oil presented to the media as green was fuel for a new Australia-based campaign group called Comms Declare 4 the Climate, which is calling out PR and advertising agencies for peddling the wares of fossil fuels companies.

Comms Declare, which was founded by former journalist and Australian Red Cross communications head Belinda Noble at the beginning of last year, now has around 80 agency and 300 individual members who have declared that they will not work for dirty energy clients.

They are not alone. In the United States, Clean Creatives is a collective of advertising agencies who have pledged to avoid working for fossil fuels clients, trade associations, or front groups. After launching last year, the group already has 146 agency and 600 individual members, although none are part of the major global communications groups which dominate the US$350 billion industry.

“

If agencies continue to help the fossil fuel industry greenwash, they are going to start losing talent.

Matt Bray, creative director, Comms Declare

Clean Creatives has compiled a list of the biggest-polluting clients that agencies should avoid. “We think that agencies should start with the worst of the worst,” said Duncan Meisel, campaign director for Clean Creatives, at an event held 14 September by Creatives for Climate, a community group for creatives working on climate campaigns.

The companies are on the list because they are the biggest polluters, the worst greenwashers — using the most deceptive tactics to mislead the public about their intentions to decarbonise — and they are the biggest obstructionists, spending the most to stop meaningful action to limit the impact of climate change, Meisel said.

He highlighted Shell as one company that agencies should avoid, because he alleges that the company’s operating plans do not reflect the net-zero emissions target it set in February. “They are promoting something that is not at all part of their business plan. So their advertisements are deeply misleading.”

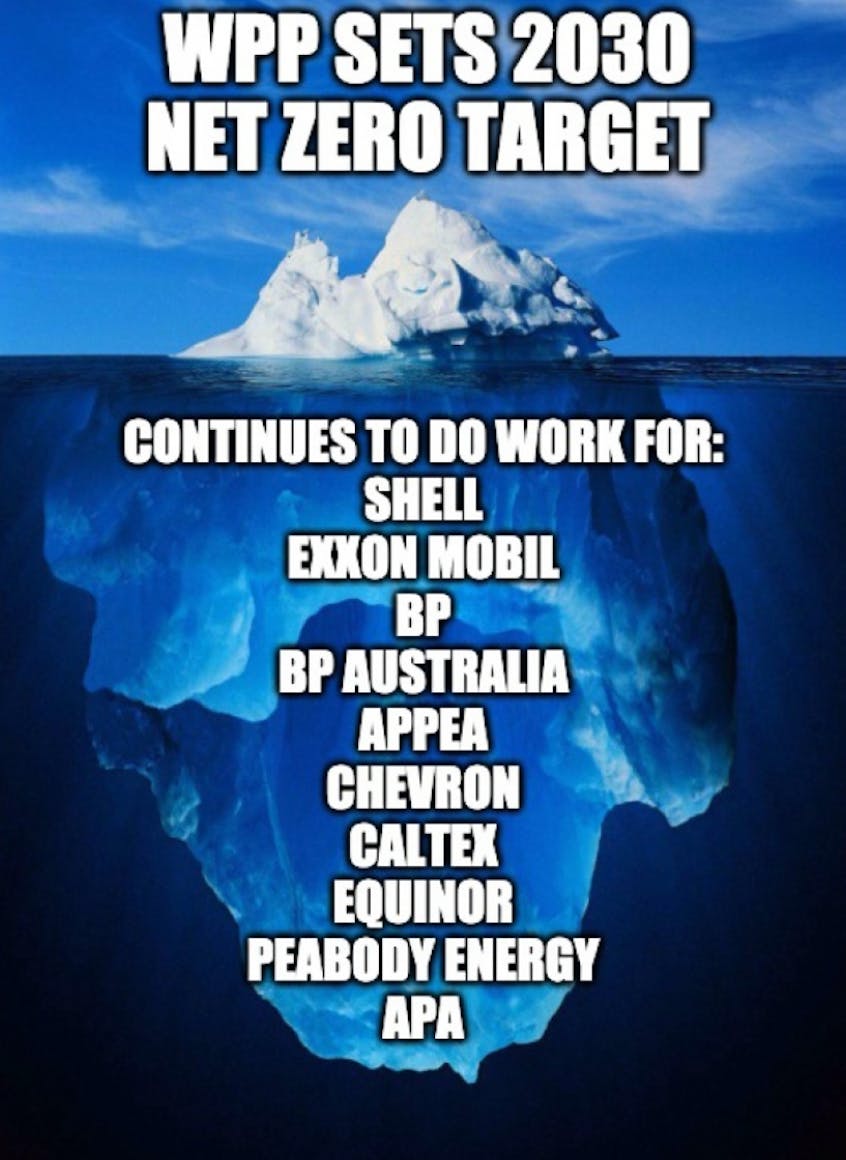

A Comms Declare Instagram post about WPP, the world’s biggest advertising group. The post reads: “Lurking below the surface of WPP’s 2030 net zero target is a lot of work for fossil fuel clients. We think that makes that net zero goal a bit fishy.”

A joint report published by Clean Creatives and Comms Declare in September, titled The F-List, showed that despite commitments from the biggest communications companies to green their operations, all have fossil fuels clients that effectively torpedo their own carbon-cutting pledges.

WPP, the world’s biggest ad agency group, has committed to reduce its emissions to net-zero, including its supply chain, by 2030. But the F-List points out that the commitment does not apply to its list of clients, which include the likes of oil majors BP, ExxonMobil, Shell and Chevron.

If WPP’s promotions help boost the sales of its client BP by just 0.3 per cent, the emissions that will result from the consumption of BP products will wipe out WPP’s climate pledge entirely, the report noted.

WPP’s big rivals, which include Tokyo-headquartered Dentsu, New York-based Omnicom, and French group Publicis, have also set net zero targets. But these pledges amount to reductions of less than seven megatonnes of carbon per year, which roughly equals one month of the carbon impact of ExxonMobil, F-List points out.

Greenwashing and the law

Tabled legislation in Europe and the United States could affect the communications industry, if it is found to be exaggerating environmental claims on behalf of big pollutors.

Lawmakers are already clamping down on fossil fuels advertising in some parts of the world. The city of Amsterdam is banning fossil fuel ads outright, Seattle has banned ads on public transport, while France is mulling a national ban on dirty energy ads.

The law is starting to turn the screws on greenwash too. Italian fuel giant Eni became one of the first companies to be prosecuted for greenwashing last year, when it was fined €5 million (US$5.94 million) for promoting its palm oil-based diesel as “green”.

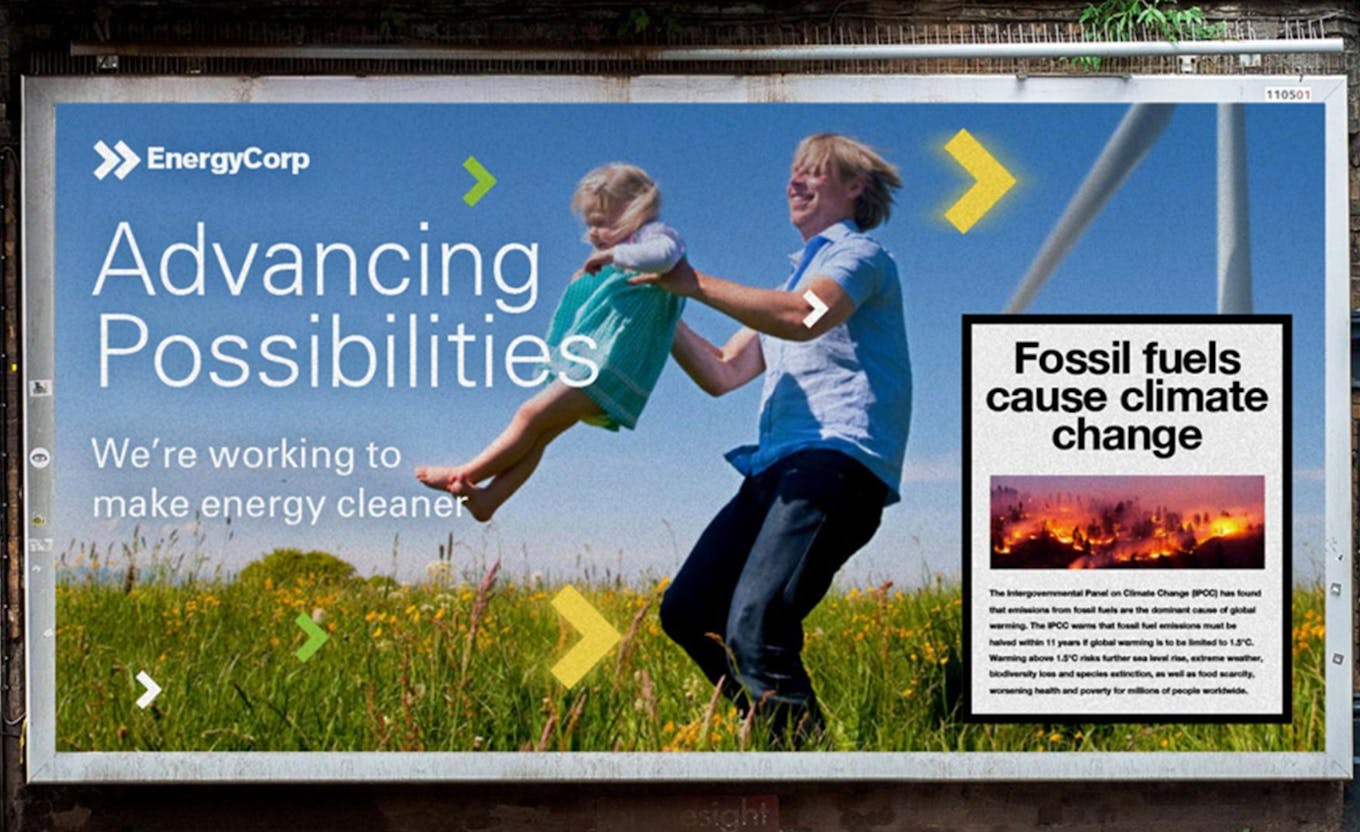

Activist law firm ClientEarth, which is calling for tobacco-style public health warnings on fossil fuels ads, took legal action against BP over misleading claims in the British oil major’s advertising.

In the Netherlands earlier this month, Shell was ordered by the country’s advertising watchdog to stop misleading campaigns that told consumers that they could offset the carbon emissions from their fuel purchases by paying extra. The oil major told consumers that the proceeds would be used for forest conversation and tree-planting projects to re-absorb harmful carbon.

An investigation found that the forests being protected by Shell are not under threat and that the company could not prove the capability of this intiative to offset the carbon emissions. A Shell spokesperson said in August that it would “study” the ruling in detail and make “consider any necessary changes to communications”.

In the United Kingdom last week, the country’s advertising watchdog, which has clamped down on Shell, BMW and low-cost airline Ryanair in recent years over trumped-up green claims, said that it would start investigating environmental claims such as “net zero” and “carbon neutral” in campaigns.

“Each of these cases bring agencies that work with fossil fuel corporations closer to legal scrutiny, and the public eye,” the F-Files wrote.

Campaigners also point to lobbying by fossil fuels firms undermining the sincerity of green claims. For instance, Shell claims it is “delivering a carbon neutral future” in its advertising, while spending millions through lobby groups such as the American Petroleum Institute (API) to block or dilute climate legislation.

Similarly, ExxonMobil promotes its investment in algae as a green alternative to petroleum while spending heavily in Facebook ads to oppose a tax reform bill in the US that includes proposals to address the climate crisis. ExxonMobil did not respond to Eco-Business’ request for comment.

API has dismissed the claim that ads by oil majors were misleading and has said that the industry was trying to find balance between climate action and responding to the needs of customers.

Shell told Eco-Business it was “increasingly transparent” in its lobbying activities, and pointed to a review of its lobbying activities published in April in which its CEO stated that it was prepared to exit groups that showed no sign that they would change to align with its own Paris Agreement-aligned view on climate change.

ClientEarth claimed BP’s campaigns misled the public by focusing on BP’s low-carbon products, when more than 96 per cent of BP’s spend was going on oil and gas. BP later withdrew the ads. ClientEarth lawyer Sophie Marjanac says: “All fossil fuel advertising should be banned unless it comes with a tobacco-style health warning about the risks of climate change.” Image: ClientEarth

In response to queries about greenwashing, Shell said it has a “clear” target to be net zero by 2050 “in step with society” and is “reshaping the company” to meet this goal, through measures such as carbon budgets that “steer decisions” that drive down emissions and “decouple business growth from carbon growth”.

A company spokesperson said that Shell’s total oil production peaked in 2019 with the expectation that it will continue to decline. “More than 90 per cent of our emissions come from the use of the fuels and other energy products we sell, so we must also work with our customers to reduce their emissions when that energy is used.”

In Asia, awareness of the risks of greenwashing is growing among communications professionals. In June a PR industry body, Public Relations & Communications Association of Southeast Asia, set up a working group to address the issue. It launched amid a wave of net-zero commitments and a survey that found that one in five consumers in Singapore say they do not trust sustainability claims from companies.

The founder of the working group, Janissa Ng, a former communicator for conservation group World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) who joined a PR firm earlier this year, said she worried that the PR industry was “obscuring what needs to be done” to advance sustainability in Asia.

Changing the change agents

To pressure agencies to avoid fossil fuels clients, campaigners are targeting their most prized assets: young talent.

Comms Declare is running a survey that asks communications agency staff under 30 years old to share their views on climate change and working for fossil fuels clients. The results will inform a campaign aimed at agency management.

“It will be a lever of pressure on agencies to understand that if they continue to help the fossil fuel industry greenwash, they are going to start losing the talent,” said Matt Bray, creative director of Comms Declare.

Comms Declare hopes the study’s findings will echo a January survey of young Americans which found that millennials and Gen Z staff are decreasingly willing to work for oil and gas companies, because of the sector’s climate impact.

An August report by Edelman suggested that employees are increasingly driven by personal beliefs over salaries; some 60 per cent of staff would leave a company that is doing ‘fundamentally immoral’ work, it found. (Edelman has worked for 11 fossil fuels companies since 2008, according to F-List.)

Some in the industry argue that agencies working with fossil fuels that are in the process of transitioning to clean energy should be given a break. Meisel does not agree.

“If you are 30 years old or younger, every single day of your life fossil fuels companies have known about climate change. The fact that they’re only looking to transition now shows that they really have no interest in changing their business model,” said Meisel.

“If they were serious, they would have started years ago. There needs to be reality check around this conversation,” he said.

ExxonMobil has been promoting an algal strain that it says could pave the way to a low-carbon fuel and a sustainable future that would “reduce the risk of climate change.” Image: ExxonMobil on Twitter

The lure of Big Oil pay cheques

Turning clients away in a service industry with dwindling margins is not easy, particularly in the Covid-era.

Simon Kearney is chief executive of Click2View, a medium-sized Singapore-based content agency that has worked with fossil fuels clients in the past. He says that while every agency wants to be part of the solution to climate change, “there are huge accounts out there that will be filled one way or another.”

Agency bosses must make pragmatic decisions about keeping their businesses afloat and their people employed, he said. “A big account from an oil major that is saying all the right things about decarbonising their business [is hard to resist].”

Kearney’s consults his staff, particularly the more junior employees who will suffer more from climate calamity than himself, on which clients they should work with before taking them on. “We had the opportunity to work for a tobacco company, and my team just said a flat ‘no.’”

“In principle, we don’t want to support hardcore carbon emitters and those who are recalcitrant on climate change,” said Kearney. His agency does work for big emitters, particularly in the tech sector, but he takes comfort in working for a company like Microsoft, which has made a commitment to be carbon negative by 2030 and is making the rights noises about working towards that target.

A former journalist, Kearney recommends some serious digging into indexes and ratings before taking sustainability communications projects on. “You can usually tell if something’s a bit off,” he said.

Thinking about the ‘brain print’

Key to the thinking that agencies should be responsible for their clients’ emissions is the notion that ad and PR firms create ideas that persuade consumers to buy polluting products. This is known as “scope X” or “the brain print”, and is central to the work of UK-based non-profit Purpose Disruptors.

Purpose Disruptors was set up by ad executives in 2018 to push the industry to only promote behaviour aligned with a net-zero emissions world. Last November, it launched a framework called “Ecoffectiveness”, which aims to link advertising effectiveness — which is traditionally measured in terms of the sales generated from a campaign, market share growth or profits — with carbon emissions.

Calculating the climate impact of advertising

Here’s an example of how the Ecoffectiveness framework works, using data from an advertising effectiveness awards.

A campaign by ad agency BBH for Audi in the UK, which ran from 2015 to 2017, led to GB£1.78 billion (US$2.4 billion) in revenue for the carmaker, with £2 profit generated for every £1 spent on advertising.

The carbon impact of the campaign was calculated like this: the uplift in sales driven by advertising (132,700 cars) multiplied by the total lifecycle emissions of each car sold, from the extraction of the materials used to manufacture the vehicle, to the use of the car over its whole lifetime (39 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent).

The resulting carbon impact of the campaign was 5,715,300 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

“That’s equivalent to 1.3 coal-fired power stations running continuously for a year, and more than the annual emissions of Uganda,” says one of the architects of Ecoffectiveness, Caroline Davison, managing partner and sustainability lead of B Corp-certified ad agency Elvis.

To lower the carbon impact of its advertising, Davison recommended Audi switch its strategy to promote its electric marques and in ads depict cars full of people rather than lone drivers to encourage car-sharing.

The framework encourages advertisers to report the carbon impact of their campaigns — or return on carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) — and aims to build insights into the ways brands can drive profitable growth through advertising without increasing emissions.

“I came to realise that the better I was at my job, the more damage I did,” said Jonathan Wise, co-founder of Purpose Disruptors at the launch event for Ecoffectiveness earlier this year. Wise was previously an advertising planner and now runs The Comms Lab, which aims to create advertising that has positive impact.

Ecoffectiveness has a way to go to gain traction. Wise admitted that the uptake 10 months after launch has been “really limited” among the big ad agencies. This is because agencies have chosen to focus on reducing their operational emissions — such as the carbon impact of producing a television commercial or erecting a billboard — and so far skirted around “the original purpose of advertising, which is to drive consumption,” he said.

The industry’s response to the Creative Climate Disclosure, a framework devised by UK-based sustainability agency Futerra for agencies to come clean on where their revenue comes from and declare their “climate conflicts”, has also been lukewarm. But a time of reckoning is coming as pressure builds on ad agencies to be more accountable for their climate impact as “architects of desire”, said Wise.

“We’re in a strange space at the moment where we’re waiting for the first big agency to jump first — or be pushed,” he told Eco-Business. “It’s just a matter of time.”

WPP, Dentsu, Edelman and other key communications groups have yet to respond to questions from Eco-Business about the climate impact of their work.

What will prompt agencies to start looking more closely at the climate impact of their creativity is either pressure from big clients, which are trying to reduce their own carbon footprint and in turn their suppliers’, or an agency that moves first to gain competitive advantage, said Wise.

“If Unilever [the world’s biggest advertiser] is looking to reduce its scope 3 emissions [the indirect emissions from its supply chain], it doesn’t take a genius to realise that it’s also going to ask its agencies to do the same,” he said. Companies have already taken their agencies to task on gender, diversity, and inclusion — and climate will be next, Wise said.

More serious climate action from the industry is likely to emerge in the run-up to the COP26 climate negotiations in November, predicted Wise, who believes that ad industry leaders will ultimately consider climate risk to be an existential threat to their business, just as digitisation was in the 2000s.

Wise said: “Climate risk is going to affect agencies just as it is affecting their clients. Agencies need to be proactive. They may take a short-term hit, but need to rethink of the purpose of advertising and ask themselves how can they can be in service of a 1.5 degree world.”