A rule requiring extra fire insulation for some rooftop solar panels is sparking concern among solar power firms in Singapore, over fears of extra costs and engineering challenges.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Property owners intending to install solar panels have been seeking clarification from their project developers, after one industrial site was recently ordered to install the extra fittings. Some projects have been paused pending clarifications, Eco-Business understands.

A clean energy trade association has met with the Singapore Civil Defence Force (SCDF), Singapore’s firefighting agency, to clarify the issue.

The episode represents a snag in densely urbanised Singapore’s ambition to maximise the deployment of solar panels across rooftops in the city-state and triple its installed capacity to 2 gigawatt-peak by 2030. Most of the questions are coming from parties involved in projects on industrial buildings, where a sizable fraction of Singapore’s solar power capacity is installed.

The rule in question requires a one-hour “fire-rated separation” between rooftop solar installations and “storage and services located below” the panel arrays, should the property not have emergency water sprinklers. The insulation is commonly achieved by installing boards containing gypsum, a fireproof material.

This clause, which is specified to only exclude “small residential” units and certain walkways, was added to SCDF’s fire code in 2020, but the required fireproof installation is not widely adopted in existing projects, based on Eco-Business’s queries.

Part of the reason is that the issue has become more apparent now, as industrial activity picks up after the Covid-19 pandemic. Project developers, some anonymously, also said that there is uncertainty over issues such as what “storage and services” entail, and what types of properties or roofs the clause applies to, even after attempts at clarification.

“Got a shock”

One randomised audit last month on a project atop a factory building resulted in a local solar energy firm, SolarGy, being told of the need to install the additional fireproofing material. A flurry of questions had followed within the industry as the word spread.

SolarGy managing director Albert Lim said he “got a shock” when asked to confirm if the property he was working on, which did not have sprinklers, had the requisite rooftop fireproofing.

Lim said the requirement had “been a subject of interpretation”, and he had believed that the insulation was only required between storage and services on the roof directly below the solar panels – not between the panels and everything else under the roof.

Lim added that the common metal roofs on factories will likely need strengthening to support the weight of both the solar panels and extra fireproof cladding. The fire-safe boards could cost up to S$150 (US$112) per square metre, increase project costs by 70 per cent and push back the time it takes for the project to break-even financially by two to three years – resulting in “severe financial impact”.

“It is time for the SCDF to review its fire safety requirements for rooftop solar installations and adopt a more pragmatic approach that balances safety requirements with promoting renewable energy adoption,” Lim said.

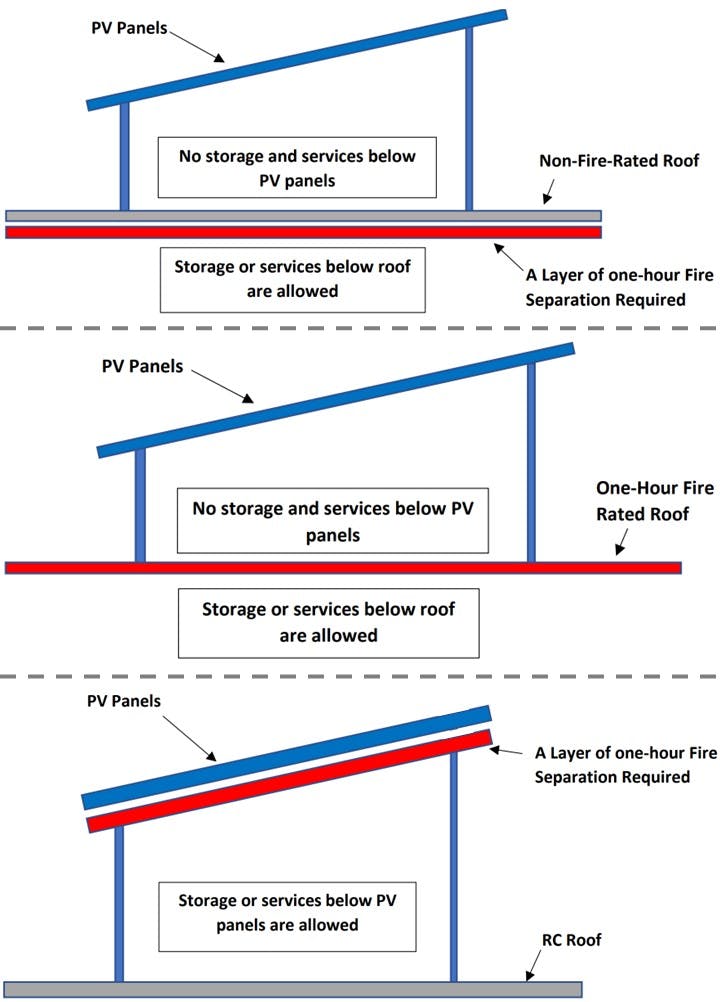

In response to queries, SCDF confirmed that “storage and services” include those located below roofs with solar panels, unless the roofs are already rated to withstand an hour of fire, or if sprinklers are installed. If the space on rooftops and below the solar panels are used, additional fire separation is required right below the solar panels.

Illustrations provided by SCDF on how it intends for the fireproofing rules for rooftop solar panels to be interpreted, for properties without emergency sprinklers. Similar guides will be sent to industry players, the agency told Eco-Business. Image: SCDF. [Click to enlarge]

The rationale, a spokesperson said, is not just to prevent solar panel fires from spreading downwards, but also for guarding against blazes spreading upwards towards the roof.

“Its importance cannot be overemphasised as evidenced in past fire incidents, where fires had burned through the roof, without fire separation, and that would have affected any photovoltaic panels if they had been installed,” the spokesperson said.

SCDF said the rule is applicable only for new buildings and projects from 1 June 2020 – the date the clause entered into force. About 200 plans have been submitted for approval since that date, and all of them were certified by professionals to comply with fire safety requirements.

The agency added that the fire code is freely accessible online, and that it remains contactable for free consultations. There have been over 30 consultations on the rule, SCDF shared.

Still, the concern among project developers like SolarGy is that the extra costs of procuring and installing the fire-rated boards could land on them, especially if they have offered to develop the entire solar power project before handing it over to the property owner. A fire sprinkler system could also cost up to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“The addition of the [fireproofing] clause and how it is applied has generally caused a bit of confusion,” said Bolong Chew, the co-founder and chief executive of Solar AI Technologies, another local rooftop solar firm.

Chew said he is speaking with “quite a few” commercial clients, and for those without sprinkler systems installed, it is generally difficult to determine if their ceilings meet the fire-safe criteria.

He explained that building blueprints may not specifically indicate the inclusion of fireproofing structures, clients may have lost contact with their property builders to check on such issues, and it isn’t easy to test for how durable their roofs are to fires.

Benedict Goh, project director of Utica Solar, an equipment supplier in Singapore, said it is “not impossible, just troublesome” to install the fire-rated separation that SCDF requires, as it would add a time penalty to projects and possibly require a reconfiguration of how the solar panels are laid across roofs.

Goh added that rooftop panels can be made safer by having more fire hydrants and extinguishers in the property, as well as not piling up flammable materials near the installations.

The Sustainable Energy Association of Singapore (SEAS), which represents over 200 firms including solar power project developers, held a meeting last week with the SCDF, along with government agencies Energy Market Authority and Enterprise Singapore, seeking to clarify matters.

“No developer or installer wants to take the risk of installing a project, only to find out after completion that it must retrofit sprinklers or fire-rated separation. We need more certainty in advance, so we can turn down projects that must have these features, and focus on those that do not,” said SEAS vice-chairman Christophe Inglin. Fire-rated separation costs more than solar panels themselves and would “kill a project’s economic viability”, he said.

“Since it seems that the presence of ‘storage or services’ is what triggers the fire separation clause, it would help to better understand SCDF’s definition of [it],” Inglin said.

The clause does not say all metal roofs must have sprinkler protection or fire-rated boards, Inglin stressed, referring to concern from developers working on industrial projects.

He said SEAS, SCDF and Enterprise Singapore have agreed to work together to better explain the regulations, such as by providing case studies and illustrations. The parties could also consider “alternative means” of achieving acceptable fire separation, he said.

The SCDF spokesperson added that SEAS will help to disseminate information in a design guidebook at events, and both parties will hold regular dialogues on solar panel-related issues.

Dr Thomas Reindl, deputy chief executive of the Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore at the National University of Singapore, said that solar panels in Singapore are tested and certified to international standards, and its materials are selected for low fire risk and a lifespan of over 20 years.

Reindl said that “origin fires”, where the blaze is started by solar panels, are “uncommon”. However, panels could still burn in building fires.

“It is often overlooked that fire codes not only try to prevent fires or mitigate the spread of fires, but also aim to ensure safe rescue operations, with or without the presence of fires,” he said.

Reindl said that the high number of buildings and dense population in Singapore “likely leads to a latent perception that fire spread could be more detrimental than elsewhere”.

“Therefore, in many cases, the initial fire code tends to be more comprehensive in considering such possibilities, but then gets reviewed over time as more field experience becomes available,” he said, adding that there is always a trade-off between cost and keeping fire risks low.

Cloudy Singapore’s solar motivation

Solar power is one of the ways Singapore is trying to decarbonise its power generation, along with hydrogen fuel, carbon capture and power imports. The city-state has a 2050 net-zero emissions target that requires it to shift away from natural gas, which is used for some 95 per cent of electricity generation.

Energy from the sun is one of the cleanest sources of electricity commercially available today, but domestic projects, even when fitted with large batteries, are expected to only meet 3 per cent of Singapore’s energy demand in 2030. The authorities attribute the low figure to the island’s cloudiness and lack of space.

Still, there have been efforts to put more solar panels on buildings. In recent years, they have been installed on the rooftops of Singapore’s many public housing flats. Singapore government agency JTC Corporation, which owns swaths of industrial land in the city-state, has been mandating rooftop solar panel installations for lease allocations and renewals for properties with sizable roof dimensions.

Peak installed capacity across the island has risen from 125 megawatts (MW) in 2016 to 632MW in 2021. Over 60 per cent of current solar capacity is installed on non-residential property, according to the country’s energy regulator.

Solar power providers had also been unhappy with a fire code update back in 2015 requiring rooftop panel installations to be paired with exit staircases. SCDF had said then that the rules were essential to minimising hazards and protecting lives. The provision remains in place today.