Disagreement on whether mineral extraction at the bottom of the sea should be allowed spilled into climate talks at the COP27 summit in Egypt, with France calling for a ban and Cook Islands in favour.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

French president Emmanuel Macron said on Monday (7 November) that France is “supporting the prohibition of any seabed exploitation” due to the need to preserve biodiversity.

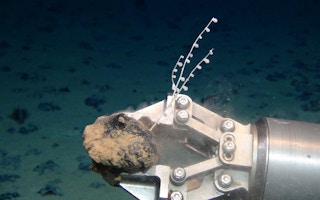

Seabed mining generally involves the use of underwater tractors to sweep the seafloor for chunks of metals like cobalt, nickel and copper – minerals considered key to mass producing climate gadgets like electric cars.

Critics fear the activity will destroy marine ecosystems that are currently poorly studied. Large-scale ocean mining has not started, but some countries have been carrying out surveys to assess commercial and technical feasibility.

Macron has previously spoken out against seabed mining, even though France holds an active seabed exploration licence via a national research institute, valid till end-2029.

“I would like to confirm this position [on seabed mining], and I will do so in other international fora,” Macron said.

About 10 countries in the council of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a United Nations-affiliated group, called for a temporary ban last week, so that more studies can be done.

Such calls were rebutted at COP27 by Cook Islands prime minister Mark Brown on Tuesday (8 November).

“Do not tell me to ignore the potential for promoting the energy transition by not exploring these much needed minerals for the green revolution that sit in my ocean,” Brown said. The Cook Islands, situated in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, has sizable manganese reserves in the waters of its exclusive economic zone.

Brown said there have been years of research on ocean resources, and that environmental protection in many Pacific nations is “far better” than countries calling for the mining moratorium, which also “emit carbon at thousands of times the rate of the island nations.

Countries that earlier called for the halt on seabed mining include Germany – which also controls a deep-sea mining concession – Spain, New Zealand, Chile and Panama, along with two Pacific island countries, Fiji and Micronesia.

Brown added that some of these countries “continue through their profit-driven actions to neglect the climate change responsibilities” and provide financing mechanisms that result in higher debt for Pacific nations.

Pacific countries such as Tonga, Palau and Tuvalu, echoed criticisms on the lack of climate financing provided by rich countries and the prevalence of loans instead of grants for such transactions at a high-level segment of COP27 that took place on November 7 and 8. But Cook Islands is the only Asia Pacific party to have brought up the issue of seabed mining.

Other countries that support seabed mining include Singapore, Norway, China, Korea, Japan and the United Kingdom.

Efforts are currently underway to develop international regulations that would pave the way for commercial seabed mining by July 2023, a deadline critics say is too rushed. There is growing doubt at an ongoing ISA council meeting if the deadline can be met.

A study published in July found that noise from a single seabed mine can travel 500 kilometres and potentially wreck the sonic environment for marine animals that rely on sound to communicate and navigate in deep water.

Australian mining magnate Andrew Forrest, who owns one of the largest mining firms in the world, said at COP27 on Tuesday (November 8) that his non-profit Minderoo Foundation supports a moratorium on deep-sea mining.

Meanwhile, land-based exploration and mining for metals critical to the energy transition have also picked up pace, leading to warnings of forest loss and human rights abuses in weaker jurisdictions.