In the final stretch of the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), the stalemate between developed and developing countries on climate finance continues to stall negotiations.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Sourcing the finance for climate adaption and mitigation efforts has been one of the biggest challenges faced by disaster-prone countries like the Philippines in forging a new agreement at the high-stakes conference.

In the current round of COP talks, climate-vulnerable countries charge that they should be compensated by developed, rich nations for their historical contributions to global greenhouse gases (GHGs) and the damage that they have caused to the environment that cannot be adapted to or avoided.

The Philippine envoys went to Glasglow prioritising climate finance, with the country’s finance minister at the helm of the delegation, also filled with his department colleagues, to crunch the numbers.

Some members of the Philippine delegation to COP26. (Clockwise from left) Carlos Dominguez III, finance secretary and head of delegation; Paola Alvarez, assistant secretary of the finance department; Teodoro Locsin, Jr, foreign affairs secretary; Albert Magalang, director from the department of environment and natural resources. A total of 19 government officials are part of the group, mostly from the finance department. Image: Philip Amiote/ Eco-Business

But a COP veteran, one of the advisors to the Philippine delegation, is advising the country’s negotiators to instead broker for technology and capacity building from rich nations.

“It is more important for us to gain their technology and know-how than outright money. That is what we are fighting for,” said the climate advisor who spoke to Eco-Business on the condition of anonymity.

The climate advisor added that even if rich nations release the long-delayed climate funds, they will likely be given as loans in most part, prompting the need for the country “to be smart about it and develop its own capacities.”

“We have all the renewable energy resources that we can tap in our country—water, wind, solar and we also have minerals to do technological development in terms of batteries through nickel. We are confident that if we are given the basic capacity for technology development, we will be at par with developed nations.”

“

It is more important for us to gain their technology and know-how than outright money. That is what we are fighting for.

Philippine climate advisor

But rich countries may be reluctant to give up their scientific know-how, especially since they are banking-on developing countries becoming their primary markets to sell technology to, the source said.

“What we throw back at them is that they owe us, and that is the form that we are going to negotiate—in the form of compensation,” said the climate advisor who has been part of deliberations ever since its beginnings at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1992.

Loren Legarda giving the national statement, as head of the Philippine delegation at COP25 in Madrid, Spain in 2019. Image: Office of the Deputy Speaker

House deputy speaker and longtime climate advocate Loren Legarda, who headed the COP25 delegation in 2019, explained that the concept of the world’s most polluting countries compensating poorer countries to curb emissions was first introduced by the Philippines during those climate talks in Madrid, Spain.

Developing nations, like the Philippines, point out there is profound inequity asking a country that emitted just 1.3 tonnes of carbon dioxide per capita in 2018 to bear the same burden as the United States or Saudi Arabia, with their respective per capita emissions of 16 and 17.5 tonnes.

The Philippines is also pushing for a global carbon incentive (GCI) that would charge countries for excess emissions and pay out a commensurate amount to those who are below the global per capita average. Financial incentives are therefore rewarded to countries that maintain a low-emitting status. This would also address the fairness problem.

“While we are not primarily responsible for the climate change problem, we do not want to contribute further to it…what we are asserting through the ongoing climate negotiations is that the developed countries deliver on their commitment to share [their] clean and climate-friendly technologies,” Legarda told Eco-Business.

Richer nations are also being asked to help to build capacity to create “fit-for-purpose” climate solutions, and a reasonable amount of funds to address the country’s gaps in financing to make the green transformation happen as soon as possible, Legarda added.

Wielding support from influential sub-groups

Country negotiators at the COP usually band together with representatives from countries with similar interests in order to exert more influence during talks.

The Philippines is part of the Group of 77 (G77), a diverse coalition of over 160 developing countries, including those from the influential Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) and the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

The Philippines has for the first time convinced the Asean and the OPEC to support the global carbon incentive concept and include it in their official position statements.

Oil-rich nations that form the OPEC readily support the emissions avoidance concept because “their profits will double,” said the climate advisor.

If the incentives become part of the Paris Agreement, then countries with a low-emitting status will get money to invest in clean technology, at the same time they get to keep the fossil fuel resource that they can transform into petrochemicals, the advisor added.

The counselor also explained that negotiators have to understand the motivations of each bloc. For instance, the advisor said the low-lying countries in the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Latin American blocs are “so easily bought by the West” because they need the richer nations for places to migrate to.

“You have to understand the interest of the sub-groups. You cannot contradict them, but look for the commonality,” the source said.

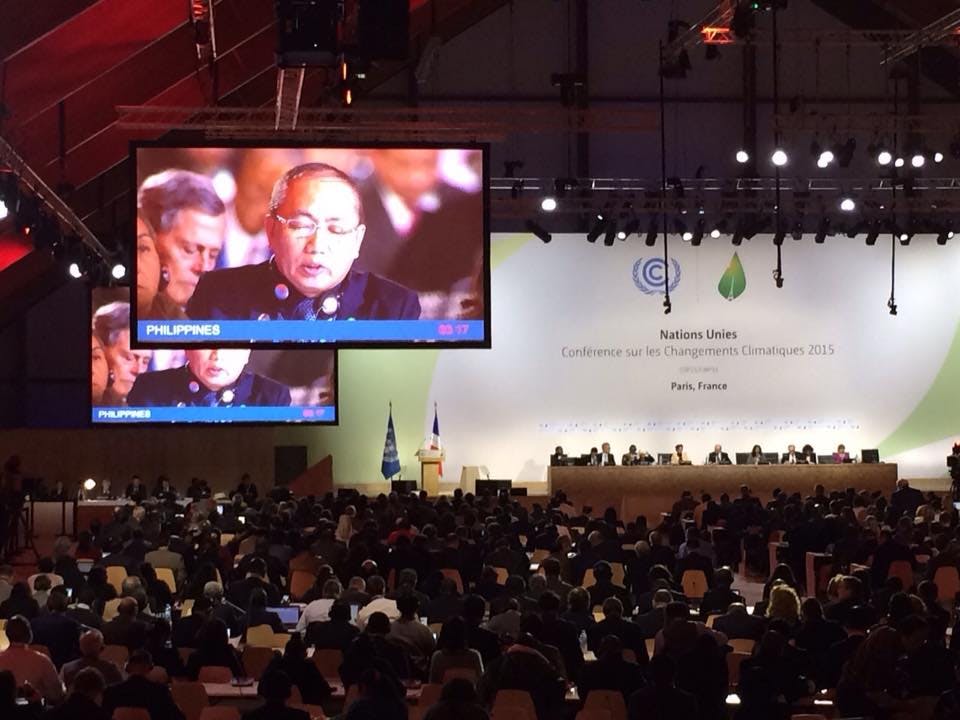

Climate Change commissioner Emmanuel de Guzman giving the national statement at the COP21 in Paris, France in 2015. Image: Climate Change Commission

Emmanuel de Guzman, vice chairperson of the Climate Change Commission, which represents the Philippines at the annual climate summit, emphasised the significance of gaining support from influential groups to advance what the country is campaigning for.

De Guzman led the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF), a group of countries most threatened by climate change, when he headed the Philippine delegation to COP21 in Paris, France in 2015. This COP subsequently became hugely significant for striking a legally binding treaty on reducing greenhouse gas emissions to curb the global temperature increase.

The CVF called for a highly ambitious long-term temperature goal of below 1.5°C to avert a climate crisis, with much at stake for the Philippines that had been battered by violent typhoons displacing thousands of people a few months before climate talks began.

Although not a negotiating bloc, the CVF was regarded as the voice of the vulnerable, especially when its members doubled to a 43-strong group, representing a billion people globally, during the historic 2015 climate summit.

“I recall the tough negotiations then. In one ministerial thematic discussion on ambition and equity, responding to another country’s intervention that strongly asserted the setting of the goal to 2°C, I had to state on behalf of the CVF, that there will be no accord to speak of without any reference to the 1.5°C goal in the draft text of the agreement,” De Guzman told Eco-Business.

The entire Philippine delegation and the CVF members were “elated” when the Paris Agreement updated the text to include the 1.5°C as the global goal, De Guzman recalls.

Regardless of allegiences inside and outside negotiating blocs, emerging economies and vulnerable countries collectively urge for stronger commitments to financing adaptation and mitigation efforts and to compensate for the economic loss as a result of climate impacts.

India, one of Asia’s economic heavyweights, said on Wednesday that rich nations need to come up with US$1 trillion of cash by the end of the decade, driving up the stakes at the climate talks. With less than two days left to thrash out the details, negotiators will be racing against the clock.