Half a century ago farmers grew rice, sesame and pulses on the land around Myint Soe’s village in Myanmar. Now only paddy fields remain.

Technology has made farming easier but government policy and climate change have slashed the foods produced by villagers which they fear is killing them when combined with the explosion in fast-food. “Now we don’t know where the oils we eat come from because we buy what’s quick and cheap and easy,” said Myint Soe, 59.

He said many people are suffering from cancer, hardening of the arteries and other ailments, likely caused by eating low-quality oil, sugary drinks, salty snacks and instant noodles.

Fellow farmer Kyaw Lin, 47, said younger, thinner people were now having strokes.

What is happening in Thar Yar Su is just a microcosm of one of the world’s biggest problems - deadly diets, which have now overtaken smoking as the world’s biggest killer.

Data shows one in five deaths worldwide in 2017 was linked to unhealthy diets in both poor and rich countries as burgers and soda replaced traditional diets and a warming planet impacted the variety of crops grown.

“

We cannot only focus on tackling hunger anymore. We are witnessing the globalisation of obesity.

Jose Graziano da Silva, head, UN Food and Agriculture Organization

The Global Burden of Disease study by the US-based Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation said unhealthy eating is killing 11 million people a year, up from 8 million in 1990—while smoking kills about 8 million people a year.

Meanwhile billions of people lack the nutrients their bodies need.

United Nations’ figures show the global population is both hungrier and heavier than it was five years ago, and food and policy experts fear the escalating food crisis could fuel conflicts and migration without action to reverse this trend.

“We cannot only focus on tackling hunger anymore,” Jose Graziano da Silva, head of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), said of the agency’s plans for the next two years. “We are witnessing the globalisation of obesity.”

Tipping point

Jessica Fanzo, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and co-chair of the annual Global Nutrition Report—described as the world’s most comprehensive report on nutrition—said diets were “the number one cause of disease, disability and death”.

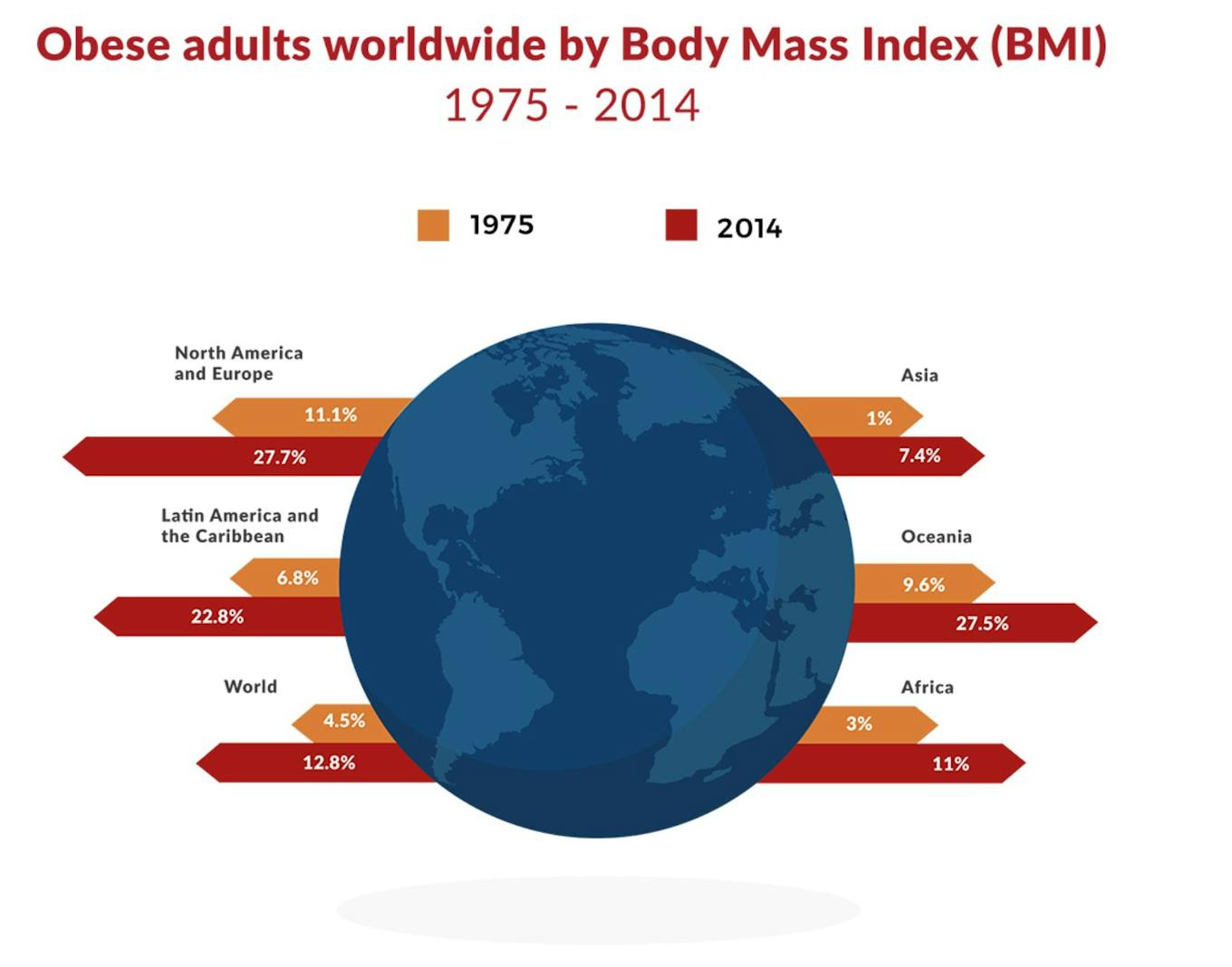

Source: UN Food and Agriculture Organization/WHO

“We’ve already reached the tipping point,” she added, emphasising that “massive changes” were needed.

Too many children are not growing and developing properly due to a lack of food while obesity is escalating, she said.

After decades of concentrating on how to feed an expanding global population, political leaders are realising that nutrition—not hunger—is the new frontier, and the focus is shifting from providing enough food to food that is good.

Alan Dangour, professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said governments have not thought enough about how environmental change will impact food.

“We could have successful trade policies which enable food to be passed between countries in a sensible way, in a fair way,” he added. “If that doesn’t happen, we could see civil unrest (and) mass migration.”

Gerda Verburg, UN assistant secretary-general and coordinator of the Scaling Up Nutrition Movement, told a public forum in Rome this year that the future of food was “not in the calories … but in the quality and diversity”.

Governments, companies and aid agencies are now racing to shake up the world’s unhealthy food habits, using legislation, educational campaigns, new and reformulated products, and greener ways of farming.

The challenges, however, are huge—not least because climate change threatens to reduce both the quantity and quality of crops, lowering yields.

Nutrition researchers said healthier, plant-based traditional foods and plant species are being shunned for Western fast-food diets laden with sugar, salt and fat.

The fruits and vegetables backed by nutritionists as crucial to good health were expensive for many, while research funding for them was “virtually non-existent”, said Emmy Simmons, senior adviser at the Washington DC-based think-tank Center for Strategic and International Studies.

That is why the farm sector must adapt to make healthier foods accessible to all, said Marie Ruel, director of poverty, health and nutrition for the Washington-based International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Fast food frenzy

The latest Global Burden of Disease study found the world on average ate only 12 per cent of the recommended amount of nuts and seeds—but drank 10 times more sugary drinks and consumed nearly twice as much processed meats.

Modern diets are contributing to ballooning overweight and obesity figures, and a rise in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as stroke, cancer, diabetes and heart disease.

Treating these diseases will cost the world more than $30 trillion—about 40 per cent of today’s global GDP—between 2010 and 2030, according to a report from the World Economic Forum and Harvard University.

“Today, not a single country has been able to reverse the trend in obesity and NCDs,” said Karel Callens, deputy leader of FAO’s strategic programme to end hunger and malnutrition.

“People are starting to suffer from all those chronic diseases at a much earlier age because now they’re getting exposed to poor nutrition, bad diets and lifestyles from a much earlier age.”

This situation could cause life expectancies to fall, experts warned, including in wealthy countries like Spain, home to the famed Mediterranean diet long praised by nutritionists for being rich in olive oil, fish and fresh produce.

For that traditional diet has been abandoned by the younger generation in favour of fast-foods like burgers, sodas and french fries, said Miguel Angel Martinez-Gonzalez, professor of preventive medicine at the University of Navarra in Pamplona.

This was the main reason about 35 per cent of Spanish adults are now obese and close to another 35 per cent overweight, he said.

“This is a failure and a humiliation for public health,” said Martinez-Gonzalez.

Big food corporations have put a lot of effort and money into thwarting public campaigns and research to improve diets, he said, a charge echoed by other scientists and nutritionists.

For example, in 2016, companies making sugary drinks spent almost $50 million lobbying against US government initiatives to reduce consumption of the beverages, wrote a team of experts led by New Zealand’s University of Auckland in January.

In Africa, the situation looks particularly dire, said IFPRI’s Ruel, as economies, populations and cities are predicted to expand quickly in the coming decades.

Hunger alongside obesity and an emphasis on calorific staple crops, together with rising incomes and availability of unhealthy foods bode ill for the continent, she said.

Asian nations are fighting similar challenges.

Myanmar hopes to diversify what its people eat and grow to help the 30 per cent of adolescent girls now anaemic due mainly due iron deficiencies and one-fifth of women who are overweight.

That includes cultivating crops other than the staple rice - such as pulses, vegetables and fruit - using better fertilisers and improving livestock production, said Kyaw Swe Lin, director-general at the agriculture ministry.

Changing climate

Additional threats to diets stem from the world’s failure to rein in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, the main greenhouse gas that is heating up the planet, according to scientists.

Agriculture, forestry and other uses of land account for nearly a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions, according to the FAO.

Atmospheric concentrations of CO2 emitted by burning fossil fuels, clearing forests and other actions could reach 550 parts per million (ppm) by 2050, reducing iron, zinc and protein levels in staple crops, said Samuel Myers, principal research scientist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

In 2017 concentrations of CO2 hit a record high of 405.5 ppm, figures from the World Meteorological Organization showed.

Vitamins and minerals are vital to human development, disease prevention and wellbeing, yet more than 2 billion people are estimated to be deficient in micronutrients, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Working with scientists growing six staple foods across three continents, Myers and colleagues estimated that in 2050, emissions would cause zinc-deficiency in an additional 175 million people and protein-deficiency in 122 million more.

South and Southeast Asia, Africa and the Middle East would be most at risk, but the nutrient reductions may be less obvious than a loss of calories, so people may not adapt their diets without a push, they added.

On the other hand, hotter temperatures could actually offset nutrition loss linked to higher CO2 levels, said a study by researchers from the University of Illinois and US Department of Agriculture (USDA) published in January.

This two-year field study of soybeans found increasing temperatures by about 3 degrees Celsius (5.4F) boosted the amount of iron and zinc in the crop.

They are now trying to understand the causes and whether humidity plays a part, said Carl Bernacchi, a scientist at the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service.

Rising temperatures and erratic rainfall associated with climate change would also exacerbate water scarcity, change the relationships between crops, pests and pathogens, and shrink the size of fish, scientists have warned.

This story was published with permission from Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, climate change, women’s and LGBT+ rights, human trafficking and property rights. Read the full story.