Half of Asia’s biggest banks still have no restrictions on coal finance, and the rest that do – namely the major Singapore and Japanese banks – only have weak restrictions with narrow project finance screens, a new study found.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Since 2021, all three Singaporean banking giants DBS, OCBC and UOB committed to cease financing new coal power projects. Japan’s megabanks Mizuho, MUFG and SMBC have also pledged to stop funding new coal mining projects as of 2022.

But lax restrictions in corporate finance to coal developers – alongside the expansion of captive coal power in Indonesia as well as coal developers increasingly seeking out domestic banks and private equity investors to finance their operations – are creating new coal financing “havens” in the region.

“Even though Singapore and Japanese banks, who are leaders in relative terms, have some policies on restricting project finance for coal, none of them are showing any interest in restricting corporate financing,” said Will O’Sullivan, a climate campaigner at Dutch non-governmental organisation (NGO) BankTrack.

The campaign group analysed the coal policies of 30 major banks with over US$8 trillion in collective assets under management across India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand.

Most Asian banks whose coal investment policies were evaluated across five criteria (projects, expansion, relative threshold, absolute threshold and phase-out) scored zero across all criteria, meaning they have no public commitments to exclude coal from their investment portfolios. Image: BankTrack’s Coal Havens report.

Globally, loans to specific coal-fired power projects are on the decline. Coal project financing outside of China hit a 12-year low in 2022 of US$544 million, according to United States-based think tank Global Energy Monitor.

But scrutiny that focuses on project finance overlooks massive loopholes in the coal policies of Asia’s top banks: corporate finance and capital markets.

Though banks might have stopped giving out project finance, they can continue to lend to the developers of those same coal power projects through general purpose corporate lending and capital markets facilitation, such as bond underwriting.

The shift towards corporate finance for coal makes it more difficult to trace how the money gets spent, especially when extended to companies with sprawling commercial interests.

For instance, it would be almost impossible to identify the end use of a general purpose corporate loan to the Filipino conglomerate San Miguel Corporation, which is one of Southeast Asia’s largest coal and gas developers, and simultaneously involved in producing beer and batteries.

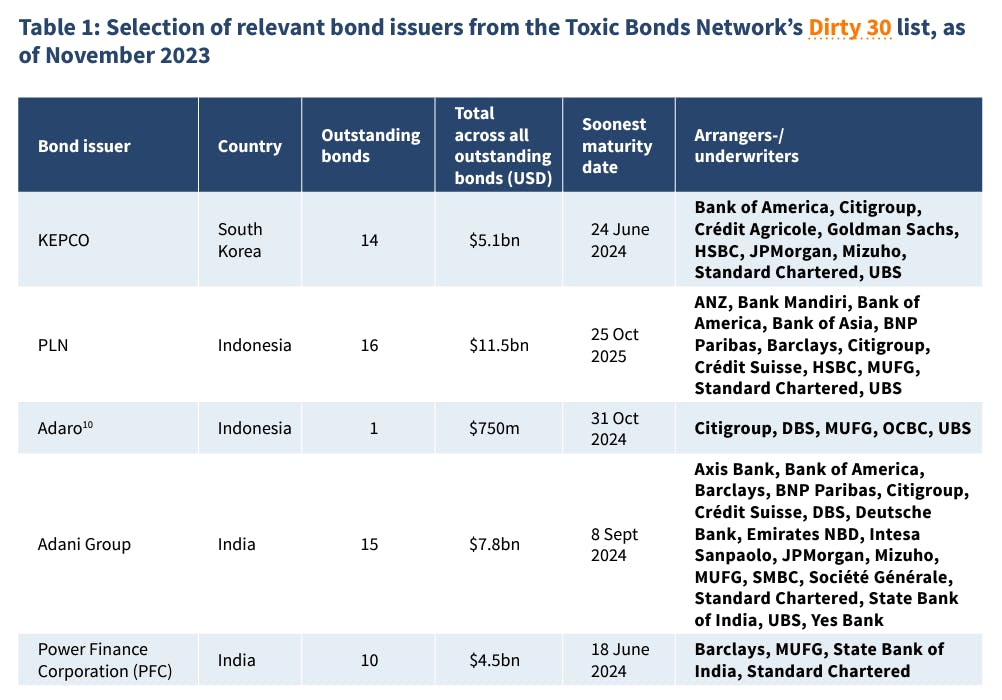

Based on data from Toxic Bonds Network, a global coalition of NGOs tracking the bond market’s financing of fossil fuels, Singapore’s DBS and OCBC as well as Japan’s MUFG were involved in underwriting US$750 million of global bonds issued by Indonesia’s largest coal company Adaro, which are set to mature later this October.

Meanwhile, India’s largest private coal mining company Adani Group has 15 bonds worth US$7.8 billion that were underwritten by a consortium of international banks that included DBS, Mizuho, MUFG and SMBC, set to mature in September.

Major Singapore and Japanese banks continue to underwrite bond issuances to coal developers like Indonesia’s Adaro and India’s Adani Group. Image: BankTrack’s Coal Havens report.

In the Philippines, bonds underwritten by domestic Filipino banks since 2020 account for 83 per cent of coal financing – a nearly threefold jump from the 28 per cent of financing they represented from 2009 to 2020, according to the NGO Centre for Energy Ecology and Development.

Unlike financed emissions, facilitated emissions generated from underwriting-related activities are still excluded from the reduction targets of most financial institutions. This is set to change on the back of the launch in December of the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF)’s long-awaited facilitated emissions standard after years of contentious debate.

While welcomed by many environmental groups, others like ShareAction criticised PCAF’s standard for not going far enough, as it only requires banks to report one-third of their capital market emissions.

Captive coal carve-outs

The report noted that private coal plants supplying power exclusively to industrial facilities like nickel mines, aluminium smelters or steel plants – also known as captive coal plants – are growing in Indonesia and account for three-quarters of the country’s total planned 18.8 gigawatts of new coal capacity.

However, captive coal is currently excluded from the coal phase-out plans of most financiers in this region and beyond.

In 2021, Singapore lenders DBS and OCBC were among the ten banks that secured US$625 million in financing for a nickel smelter powered by a 114 megawatt captive coal power plant on Obi Island, Indonesia.

Notably, captive coal plants were omitted from Indonesia’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) investment plan, a G7-led funding programme to decarbonise the power sector. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank’s private sector lending arm, also excludes captive coal-fired power plants used for industrial applications in its sustainability policies which require clients to reduce their coal exposure to near zero by 2030 and, as of 2023, to stop providing project finance for new coal projects.

Additionally, experts have raised concerns over Indonesia’s financial regulator, the OKJ, reportedly considering giving captive coal plants the cleanest label in its green taxonomy, which would classify them in the same tier as renewable energy projects.

Domestic banks stepping up in the wrong way

As international banks withdraw coal financing due to heightened public scrutiny, domestic banks and private equity investors are stepping in.

A case in point was when Indonesia’s Adaro reportedly struggled to raise money last year for a “sustainable” smelter project from international banks that it had close links to, including DBS, British lender Standard Chartered and European banks BNP Paribas, ING and Commerzbank.

The project ended up being financed by four Indonesian banks – Bank Central Asia (BCA), Bank Mandiri, Bank Negara Indonesia (BNI) and Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) – alongside Permata Bank, a subsidiary of Bangkok Bank.

In India, seven and a half times more finance was provided collectively by domestic financiers (US$86 billion) for thermal coal, compared to international lenders (US$6.5 billion) from 2005 to August 2023, according to the non-profit Centre for Financial Accountability.

When speaking to Eco-Business, the report’s author O’Sullivan acknowledged the efforts by Singapore’s central bank, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) to get local banks to engage with carbon-intensive companies and to finance Asia’s early retirement of coal.

“MAS is encouraging banks to be involved in early coal retirement, but we are currently far away from that reality,” said O’Sullivan. “Any good faith contribution by banks to the energy transition would involve implementing coal policies that says you can contribute to that, but you won’t finance a company which generates, say, 50 per cent of its revenue from coal.”

“The current reality is one where vast amounts of money, with no conditions, are going to coal developers which are happily building a pipeline of coal power and mining projects.”