China has been hit with power cuts stemming from coal shortages as the world’s largest polluter attempts to reduce its carbon dioxide emissions. In a sign of the extent of the coal supply crunch, China has tapped into Australian coal from storage, despite a year-long standoff between the two countries that led to an unofficial import ban on the fuel.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

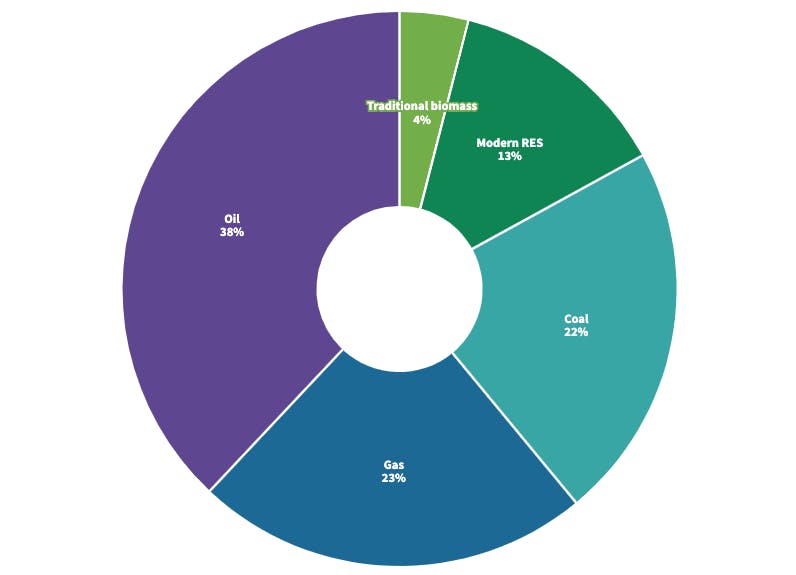

ASEAN total primary energy supply (2019), ASEAN Energy Database [click to enlarge]. Image: Eco-Business

The scramble by the world’s top consumer of coal comes on the back of demand from manufacturers, industry and households, who are facing colder weather, pushing prices to record highs and triggering power shortages.

Chinese provinces have been hit with power rationing so severe that in some places factories have been allowed to operate for only two days a week, threatening economic growth and the global supply chain.

The country has urged its mining companies to boost ouput and told power operators to step-up coal imports in an “orderly manner” to ease supply constraints. Without importing from Australia, its supply shortage is likely to linger.

Australia shipped 35 million tonnes of thermal coal to China in 2020 and closer to 50 million tonnes in 2018 and 2019, according to Argus Media, a commodity price reporting group. After November 2020, overall coal imports to China dropped to near zero, according to Wood Mackenzie.

The shortages are not helped by other key suppliers facing their own technical challenges. Russia and Mongolia have limited rail capacity and shipments from Indonesia have been waylaid by wet weather.

China’s banking regulator has since asked financial institutions to raise their risk appetite for loans to coal plants “to ensure that the people live warmly through the winter”.

Last year Xi Jinping, China’s president, vowed that the world’s biggest polluter would reach peak carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. In September China pledged to end overseas coal financing. Coal represents nearly 60 per cent of the country’s electricity mix.

China is jostling for coal imports with Asia’s second economic powerhouse. India is on the brink of a widespread shortage of power. Most of the country’s coal-fired plants have enough fuel for only a few more days, according to reports by Reuters.

The country’s power plants are buckling under a surge of demand from industries as the economy rebounds from the Covid-19 pandemic. The crisis is compounded by sluggish imports of the commodity due to climbing prices.

As of Friday, the stockpiles of all coal plants averaged four days. Coal-fired plants account for about 70 per cent of India’s power source mix.

“The supply crunch is expected to persist, with the non-power sector facing the heat as imports remain the only option to meet demand but at rising costs,” ratings agency S&P’s unit CRISIL said in a report this week, adding it expected Asian coal prices to continue to increase.

Not so cheap

Coal has been front and centre for both economic titans, largely because it is cheap and abundant. But the price of coal has recently soared to all-time highs. The cost of Australia’s Newcastle port, the Asian benchmark for thermal coal, is 400 per cent higher than a low of US$48.50 in September last year. Indonesian export prices are up 30 per cent in the last three months.

Meanwhile, oil prices climbed to multi-year highs — US$81 a barrel — after the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and allies that make up the OPEC+ alliance, resisted calls to boost supply at a meeting on Monday. Some analysts believe that price of crude could rally toward US$100 a barrel. The collective of some of the world’s most powerfull oil producers said that it would stick to its existing pact of a gradual increase in oil supply.

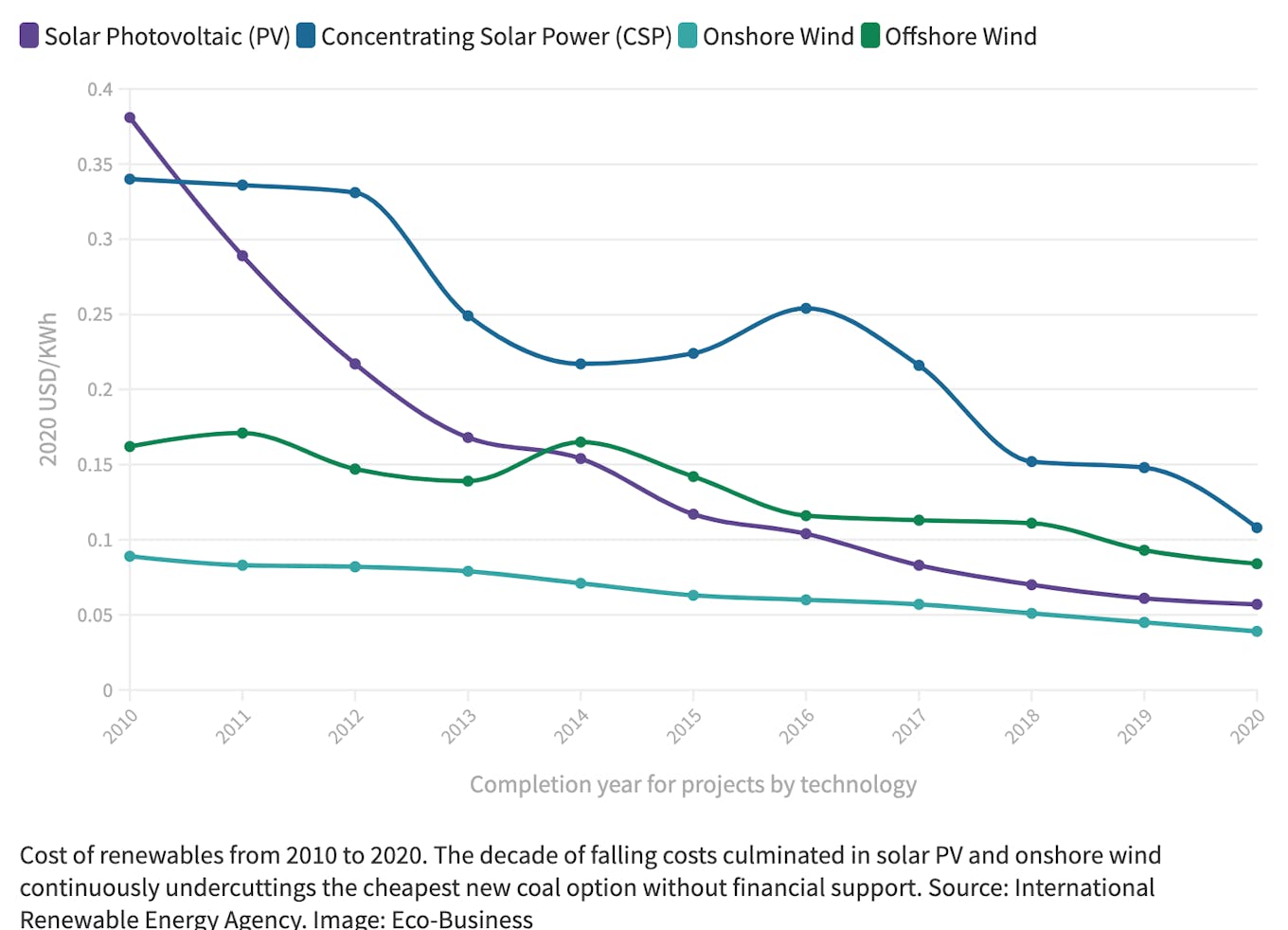

Cost of renewables from 2010 to 2020. The decade of falling costs culminated in solar PV and onshore wind continuously undercuttings the cheapest new coal option without financial support. Source: International Renewable Energy Agency. Image: Eco-Business

Despite the current price surges, coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG) could lose out to cleaner energy long-term. The energy crisis could shape the way governments, power utilities and the public respond to the transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy, said Clyde Russell, an energy columnist at Reuters.

“The rise to record highs for thermal coal, used in power plants, and spot LNG in Asia is obviously a short-term boon for producers of the fuel, but is likely a long-term negative,” Russell said in a column on Tuesday.

“For renewables such as wind and solar, the price story is their major advantage over coal and LNG, given ongoing deflation and improving technology.”

In India and China, the cost of new utility-scale solar power has fallen to levels as low as US$20-40 per megawatt-hour (MWh), making it cheaper than coal. In Thailand and Vietnam, solar and wind are also more affordable than coal, with most Southeast Asian markets expected to follow in the coming years. In Malaysia, Cambodia, and Myanmar, solar auctions have already hit prices of around US$40 per MWh.

“Chinese thermal power will be the centre of China’s energy mix for some time. This has not changed,” said Norm Waite, energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

“IEEFA does not believe China will waiver in its 30/60 commitment due to this commodity price/supply shock. If anything, China’s need to wade into international commodity markets to secure energy sources underscores its primary motivation of energy security. This may change, but so far Chinese NDRC policy toward energy efficiency targets has remained,” Waite told Eco-Business.

Pricing adjustments will benefit renewable energy sources and encourage more energy storage. “We see no reason to give up hope or doubt the country’s resolve at this point,” said Waite.

While many are hoping that this energy crunch will pull India away from its dependence on coal and LNG, others are less optimistic.

Electricity shortages due to scant coal supplies risk creating a “backlash against renewable energy” as the public and politicians realise the economic cost of achieving emission targets, said Prashanth Perumal J, editorial page writer at The Hindu, one of India’s largest English language newspapers.

In a column on Tuesday, Perumal said: “With renewable energy sources such as wind and solar energy turning out to be unreliable especially during winters, countries may be forced to rely on traditional fossil fuels and governments may need to rethink their energy policy.”