A researcher’s publication record is often considered a measure of their influence in the field and can be crucial for their career progression.

The pressure on researchers to publish high-quality work is so great that it has spawned the phrase “publish or perish”. However, the playing field of scientific publishing is highly unequal and it can be disproportionately challenging for certain groups of people — including women and researchers from the global south — to succeed in this system.

Biases in authorship make it likely that the existing bank of knowledge around climate change and its impacts is skewed towards the interests of male authors from the global north. This can create blind spots around the needs of some of the most vulnerable people to climate change, particularly women and communities in the global south.

Carbon Brief has analysed the gender and “country of affiliation” of the authors of 100 highly cited climate science papers from the past five years — mapped below — to reveal geographic and gender biases.

The analysis highlights the wide gap in publishing success between the global north and the global south. Less than 1 per cent of authors in the sample are based in Africa, while almost three-quarters are affiliated with European or North American institutions.

Furthermore, the analysis highlights the gender disparity within climate-science publishing. It finds that fewer than one-quarter of the authors are female, while only 12 out of the 100 papers analysed have female lead authors.

Carbon Brief has also spoken to a diverse range of academics about the barriers they have faced in their academic careers, the reasons for the lack of diversity in publishing, and their suggestions on how to “decolonise” academia.

For this analysis, Carbon Brief recorded the gender and country of affiliation for every author from the 100 most highly cited climate science papers of 2016-20, based on Google scholar metrics data. More than 1,300 authors are included in this analysis. (The methodology is described in full later in the article, with a link to the data.)

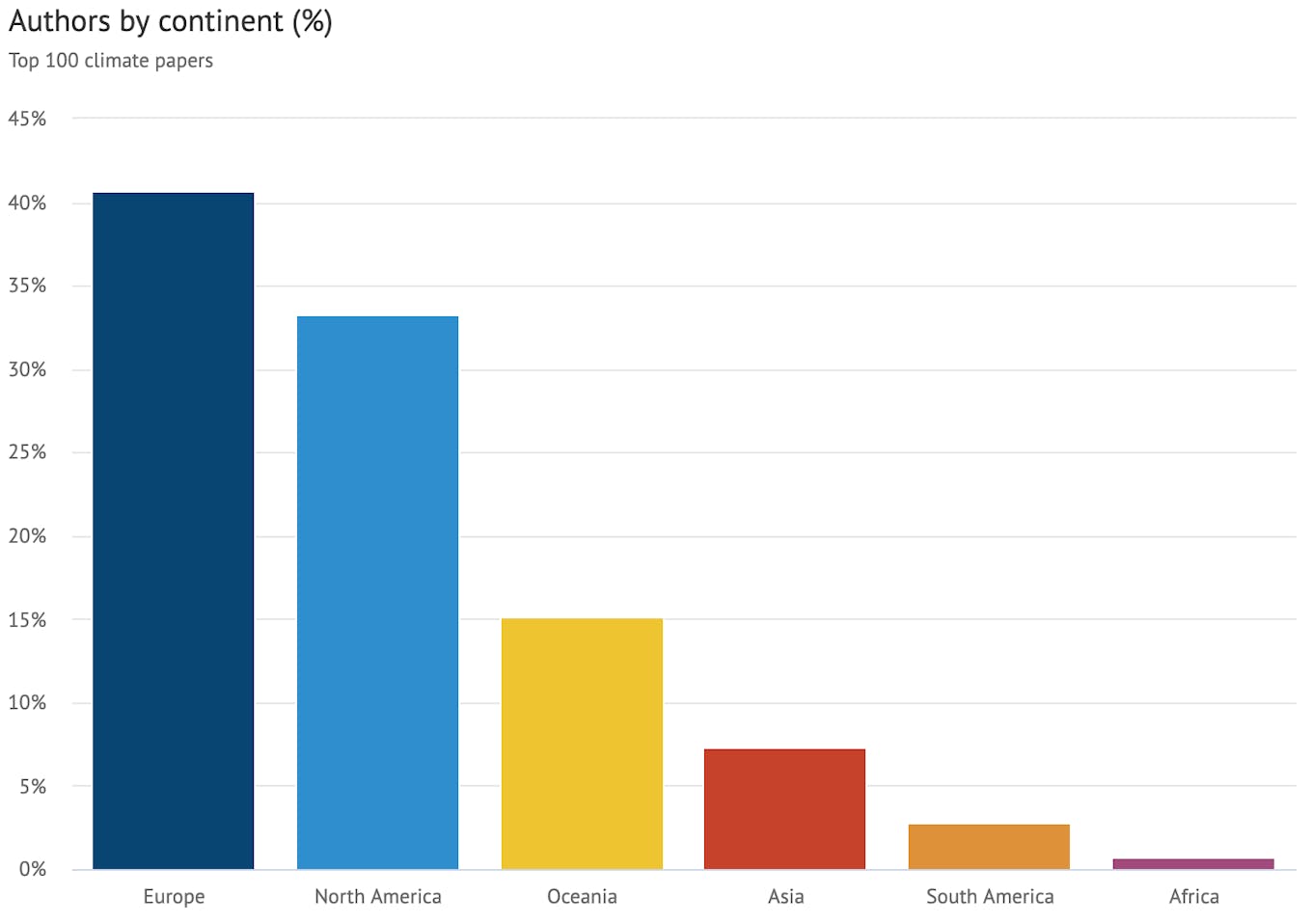

The chart below shows the institutional affiliations of all authors in this analysis, broken down by continent — Europe (dark blue), North America (light blue), Oceania (yellow), Asia (red), South America (orange) and Africa (purple).

The analysis shows that nine out of every 10 authors are affiliated with institutions from the global north — defined as North America, Europe and Oceania. Meanwhile, the entire continent of Africa, which is home to around 16 per cent of the world’s population, comprises less than 1 per cent of authors in this analysis.

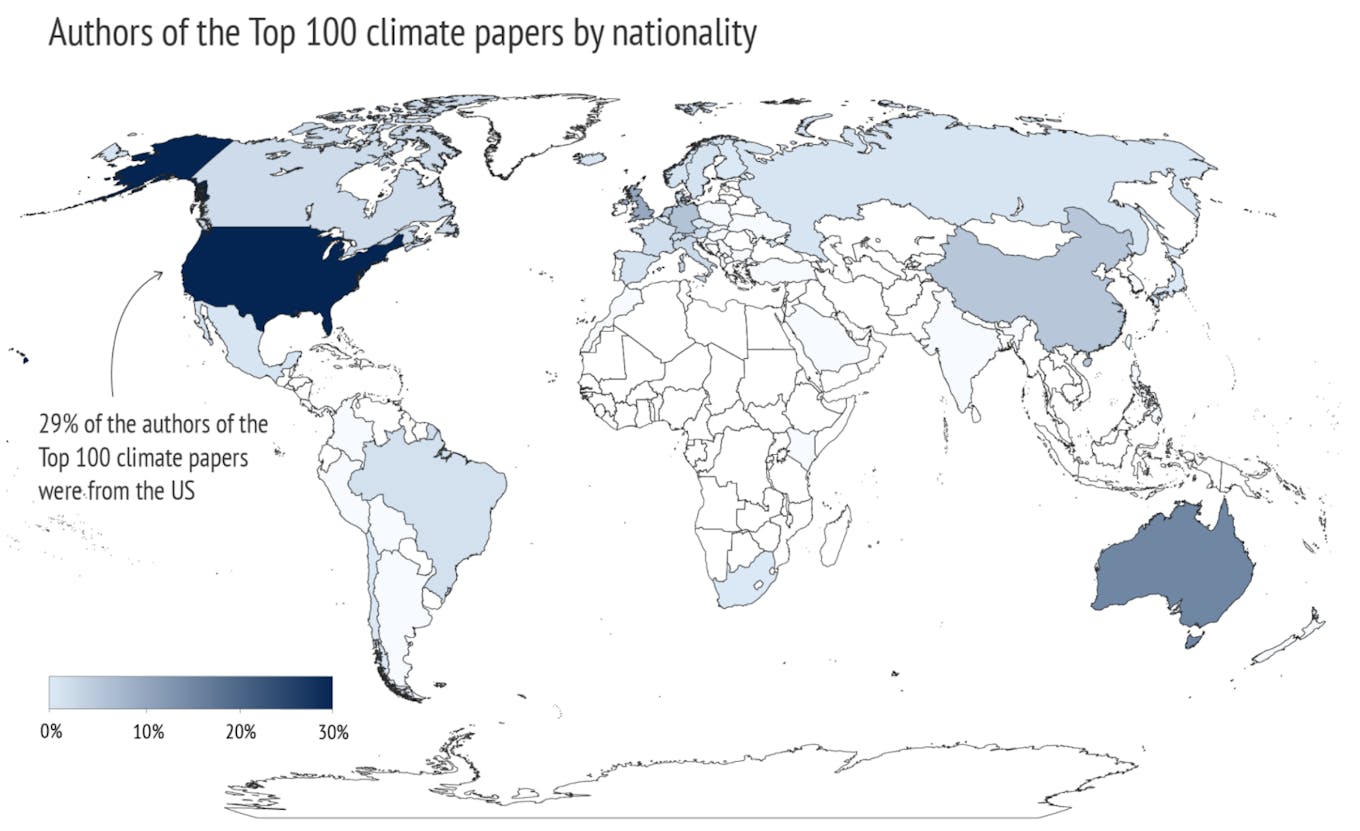

Further data analysis shows that there are also inequalities within continents. The map below shows the percentage of authors from each country in the analysis, where dark blue indicates a higher percentage. Countries that are not represented by any authors in the analysis are shown in white.

The top-ranking countries on this map are the US, Australia and the UK, which together account for more than half of all authors in this analysis (approximately 30 per cent , 15 per cent and 10 per cent , respectively). Furthermore, nine out of every 10 papers in this analysis include at least one researcher from the UK, the US or Australia.

However, one of the most striking takeaways from this map is the number of countries from Africa and Asia that are not represented in this analysis at all (shown in white). In Africa, a continent with more than 50 countries, only 10 authors are represented in this analysis — eight of whom are from South Africa.

Furthermore, in South Africa, researchers are “expected to publish in high-impact, accredited journals”, while many other African countries focus on publishing in any journal, regardless of its prestige, Chitsamatanga says.

Meanwhile, almost half of all researchers from the global south are from China — which accounts for around 6 per cent of all researchers in the analysis. In recent years, China has been pouring the equivalent of billions of US dollars into scientific research and, until recently, would pay researchers bonuses for publishing research in “top-tier” papers, in a similar way to the South African system.

Meanwhile, almost two-thirds of all European countries are included in the analysis. While the UK has the highest proportion of authors in Europe, countries including the Netherlands and Germany also have notable representation.

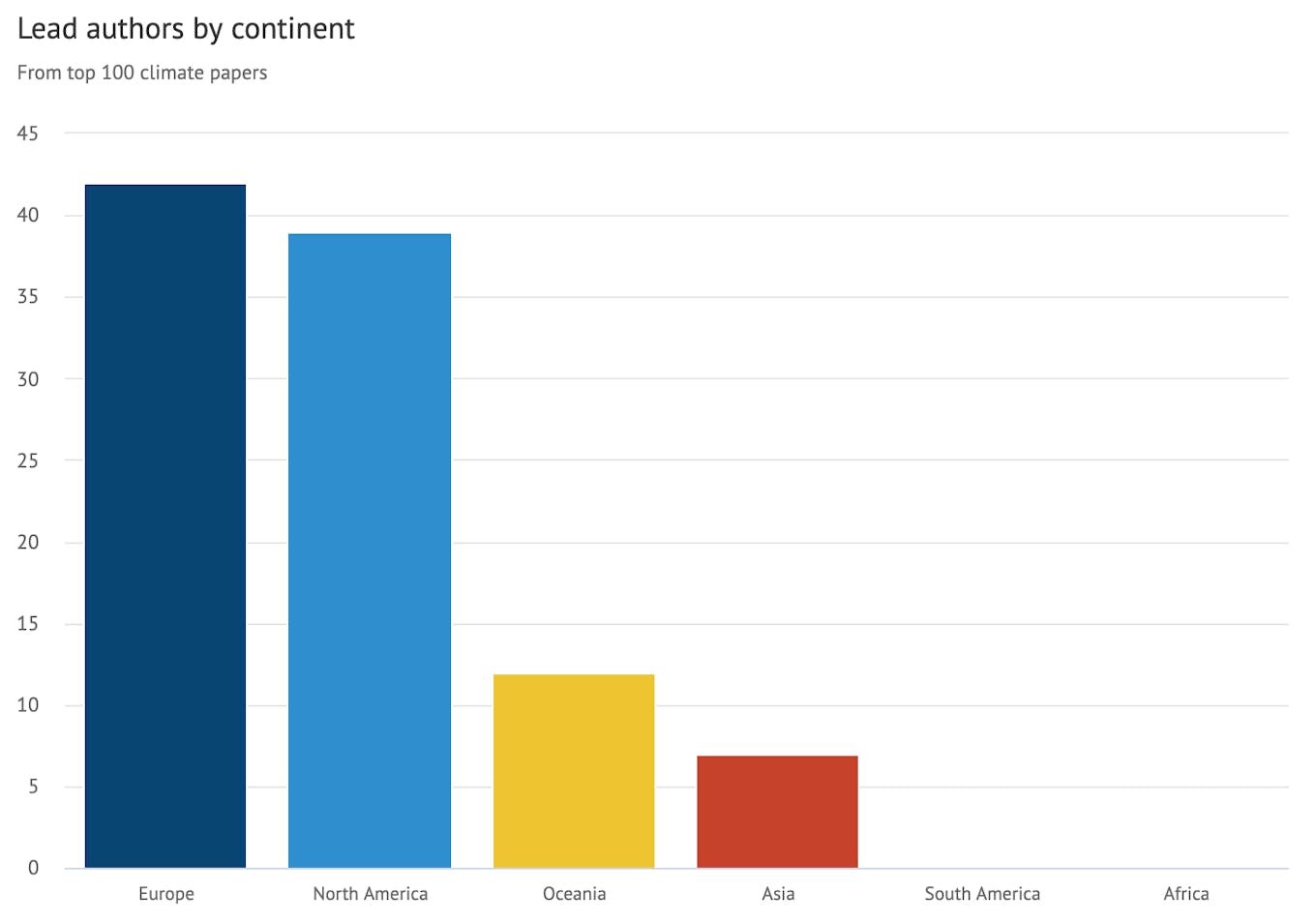

No papers in this analysis are led by a researcher from either Africa or South America. Furthermore, only seven papers are led by Asian authors — five of whom are from China.

She tells Carbon Brief that while most of the results are “completely expected”, she finds the total lack of lead authors from Africa and South America “really shocking and sad”.

There are multiple barriers to conducting research in developing countries — where funding is often low, English may not be an official language, and collaborations with richer nations are generally built on an unequal power dynamic.

Conducting scientific research is expensive — and, arguably, the most obvious issue with running climate studies from countries in the global south is the lack of funding. While the US dedicates more than 2.5 per cent of its annual GDP to “research and development”, no country in sub-saharan Africa — even the comparably rich South Africa —spends more than 1 per cent.

This funding discrepancy means that the bulk of research concerning developing countries is often not performed by local scientists, but instead by groups from the global north. One study found that European and North American institutions received 78 per cent of all funding for climate research regarding Africa over 1990-2020, while African institutions received only 14.5 per cent.

Mwampamba tells Carbon Brief that “ground-breaking research” often needs a level of technical expertise and capacity that countries in the global south do not have: “Groundbreaking research is the research that tends to get funded. But groundbreaking research usually requires more savvy tools, different kinds of data, all types of equipment and abilities that might not exist in a study site in the global south. That creates a huge divide.”

One way for scientists from the global south to overcome issues of funding and technology is to collaborate with researchers from the global north. Academic collaborations between countries are becoming increasingly common. Over the period of 2000-13, the percentage of total publications across all disciplines, not just climate science, with authors from multiple countries rose from 13 per cent to 19 per cent.

Armenteras adds that collaborations between developed and developing countries can lead to “asymmetries of power” that are “really dangerous” — allowing researchers from rich countries to “take advantage of inequality”.

For example, Armenteras explains that funding for research usually comes from countries in the global north, giving researchers from the global north more “power” over the direction that the study takes. Tensions in academic collaborations can be compounded by misconceptions about the quality of research that researchers in the global south are capable of, she adds: “They put you down and think your science must not be good…They don’t associate Colombia as a place where science can be done and often think, ‘I have to be the saviour and do the science for you’.”

Armenteras recounts one collaboration with an academic from an institution from the global north, during which she worked as hard as her fellow principal investigators from the global north, but without the funding and assistance that they assigned themselves.

“We are not slaves,” Armenteras tells Carbon Brief, “we don’t want to work for free”. She ended up quitting the project.

“Researchers in the global south are considered to be kind of like assistants. Even if they’re very much engaged in collaborations, they don’t get authorship [on papers],” Schipper adds.

Mwampamba elaborates on this dynamic, explaining the thought process of some researchers from the global north when they conduct research in poorer countries: “The northern scientist often brings his or her own grad students from the North, and they tend to view their local partners as facilitators — logistic, cultural, language, admin — rather than science collaborators. “It’s like: ‘You’re here as local partners so you make everything accessible to me and make my life easier when I’m here in this foreign country. You will interpret the cultural part, and I will do the science’.”

Another issue with cross-country scientific collaborations is the mindset of some scientists from the global north who seek to extract resources and data from developing countries without contributing to local infrastructure or science capacity — a practise known as “colonial”, “parachute”, or “helicopter” science.

Dr Fernande Adame is a researcher at the Australian Rivers Institute of Griffith University. She conducted research in Mexico for much of her life and has experienced parachute science first hand. “It’s just plain unfair,” she tells Carbon Brief. In a career column in Nature, Adame wrote: “I saw foreign scientists come to our laboratory carrying high-tech instruments that we didn’t have access to. We took the scientists to our field sites and taught them about the unique ecology of the mangroves. Sometimes they used our small laboratory to store or analyse their samples. Neither I nor anyone else on the team was ever asked to contribute to the papers that were published.”

Adame tells Carbon Brief that “a lot of scientists in places like the US still have this tradition of having the old male professor deciding who can or cannot be an author”. This process can lead to authors from developing countries being under-represented, she adds.

Armenteras tells Carbon Brief that in Colombia — a country that she calls “paradise” for collecting data on biodiversity — local researchers want their names on a paper with “the big white guy” from a northern country. So, she says, they often “kneel down to people from overseas and collect data for them, or give their [own] data away”.

While this may allow local researchers to get their names on the paper, it “doesn’t build scientific capacity in the country”, she laments. This mindset of extracting resources without contributing to local capacity extends as far as people, according to Armenteras, who recounts times when researchers from the global north asked her to send promising Colombian students to be trained.

This “brain drain” of promising researchers leaving their country to seek better prospects abroad can have a negative impact on research and development in developing countries and it stands to reason that this will have a knock-on impact on paper publications.

Publish or perish

Once academics have completed their research, there are still multiple barriers to contend with before it is published. The process of writing and publishing papers is laborious, highly competitive and can take years — even for researchers from well-established institutions from the global north.

Academics must first choose a journal whose “scope” fits well with their paper and submit a first manuscript to them. The editors of the journal can either reject the manuscript outright (known as a “desk rejection”) or send it to other scientists in the field to be “peer reviewed”.

The reviewers are asked to suggest changes to the paper — ranging from minor grammar changes to instructions to change the direction of the paper entirely. There are often multiple rounds of editing in this way before the paper is finally published. As such, it is not only the quality of the research, but also the quality of the writing that is important when submitting to a journal.

The specific format required for writing papers is defined by “the academic culture of western universities”, according to Dr Marton Demeter — a researcher at the National University of Public Service in Budapest with a specialism in “publication networks”. He tells Carbon Brief: “Global south authors are not necessarily familiar with these norms and top-tier journals are far from being inclusive in this sense: if you don’t write the paper exactly the same way as your colleagues from Harvard, your research will be considered of low quality.”

The process of writing papers can be complex, so well-funded universities often offer their students training on how to write papers and assistance to guide them through the publishing process. In contrast, academics in developing countries often do not receive the training and support that their counterparts from the global north benefit from, Schipper tells Carbon Brief: “There is a huge discrepancy between the capacity, training, skills and opportunities available for scholars in developing countries to learn how to write peer review, high quality academic journal articles [and that of scholars in developed countries].”

Schipper is on the editorial board of the journal Climate and Development. She tells Carbon Brief that she often receives submissions that are “really interesting”, but in which the author “doesn’t quite know how to write an academic paper”. Schipper notes that some journals, including hers, offer help to the authors of such manuscripts, but that this is not common practice: “If you don’t have a lot of experience in writing [papers] and you don’t know what a paper is supposed to look like, you won’t write a good abstract or introduction and the editor will say ‘forget it — it’s just not worth it, this is not a good piece of work’.”

Pathak is another editor on the same journal and explains that this lack of knowledge around how to write and publish papers does not only apply to early career researchers, but also to mid-career professionals: “I think it’s quite challenging for a developing country author from a small country to be able to publish in these journals. I know mid-career professors who are at a loss of where to start — of how to publish. But it’s not like they are less competent.”

The inaccessibility of scientific literature is also a problem for publishing. “One of the biggest issues is that people can’t access literature that they can cite,” Schipper tells Carbon Brief. She adds that when she receives a paper submission, one of the first things she looks at is how old the references are. “I think the problem of climate change is that it’s moving so rapidly…and it’s really expensive”, she says.

Pathak says that this also poses a problem for getting papers cited: “Suppose someone [from a developing country] does manage to publish a paper in a top category journal. Their developing country colleagues cannot access that paper, so the paper would likely get fewer citations from within the region.”

Conversely, researchers from well-funded universities that can afford to pay journal subscription charges and, therefore, “have access to a huge library of resources and can access everything”, Pathak adds.

To solve this problem, some journals have begun publishing “open access” articles that anyone can view. For example, Nature recently launched an open-access service, for which authors can pay a €9,500 fee to make their paper available for free.

Demeter sees open-access journals as an issue for academics from the global south. He conducted a study that concludes: “[The study] reinforces our concerns that hybrid open-access models are likely to perpetuate inequalities in knowledge production.” He tells Carbon Brief: “If open access in journals with article processing charges (APCs) become the mainstream way of publication, then global-south scholars’ chances to publish in leading journals will be even lower than today, as they wont be able to pay the high APCs — which will be easily paid by researchers working at sourceful western universities or researchers that are funded by international grants.”

Mwampamba also sees open-access publishing as “a huge barrier” for academics from low-income countries due to the cost. She notes that waivers are sometimes an option for authors from developing countries, but tells Carbon Brief that “you really have to search for them. There are all these rules that are not very explicit.”

For example, she tells Carbon Brief that often, waivers are only granted if all authors on a paper are from an institute in a developing country — not just the lead or corresponding author.

Even if academics write a high-quality paper with solid citations — and have the money to publish it — research shows that academic journals are biased in favour of “authors from the US, English-speaking countries outside the US, and prestigious academic institutions”.

Vuong tells Carbon Brief that “many top-tier journals still remain a type of ‘old-boys club’ and are not quite open to voices from the developing world”. He relays experience from is own research group that demonstrates this: “In some cases, we propose useful and worthwhile ideas and analyses, which may be rejected outright for vague reasons…But some time after those decisions, we found publications with very similar ideas, with no better technical treatments and no superior quality, published in those journals. The difference is that the authors usually came from very well-known research institutes or faculty of top-tier universities in the US, Germany, UK, etc. I can say that the playing field is unlevel.”

Part of the issue is in the peer-review process. Peer reviewers, alongside journal editors, are “gatekeepers” of science — deciding which studies are shared with the rest of the scientific community, and which are not. However, there is a well-documented bias in the system, Demeter tells Carbon Brief: “There is empirical evidence showing that both editors and reviewers found submitted manuscripts better if they think that they were submitted by professors from elite western universities.”

Pathak laments that many of her experienced colleagues will “never get a paper in a Nature journal”, because breaking into the world of academic publishing is so difficult for researchers from the global south: “All the papers that make it into major climate change journals would keep on getting cited which drives more funding and international collaborations. So for young authors from developing countries, breaking into that upper league just gets harder.”

The language barrier

For non-English-speaking academics there is also a language barrier to contend with. English is widely regarded as the “lingua franca of science” and research has shown that articles published in English are more likely to be highly cited than those published in other languages.

“We cannot deny the fact that top-tier journals are being published in English,” Vuong tells Carbon Brief. Mwampamba adds that English-language journals are universally considered the best: “There’s a clear ranking —both in universities and research institutes — that if you publish in English to an international audience your science is considered better and it boosts your CV and promotions considerably.”

Mwampamba also tells Carbon Brief that, while many of her colleagues can read in English, writing and speaking are “more challenging skills to master”. Similarly, Vuong tells Carbon Brief that even if scientists have reasonable skill in speaking English as a second language, the language barrier can still be a problem, as “writing clearly in a second language is still a hard skill to master”.

“We cannot ignore” the language barrier, Pathak tells Carbon Brief. She has been publishing in English for years, but notes that in the early days of her research career, her papers were often sent back from peer review with the comment, “extensive language edit needed”.

“In Africa, academic writing is weak compared to writing elsewhere because competition to publish topical issues remains very high,” Chitsamatanga tells Carbon Brief. As such, she says that the rejection rate for manuscripts submitted to English language journals is “very high”. To overcome these problems, many academics are forced to turn to translation services, which can be expensive.

On top of this is the issue of writing style. Mwampamba highlights that different cultures have different ways of expressing themselves which is — to some extent — also reflected in writing styles. For example, she notes that the western style of writing papers is “short and snappy”, while the Spanish style tends to be “more verbose and expressive”. She tells Carbon Brief that this presents yet another barrier to publication: “Even if someone writes the paper in Spanish and gets it translated — and the translation is perfect — the journal might still want a whole different style. This is a lack of flexibility on the part of journals and reviewers. They want to keep things in the Northern style. “Reviewers are supposed to look at the quality of the science or the arguments. But they are to some extent gatekeepers of style. I think it is a real pity that style diversity is smothered in formal communication of science. I know it contributes a lot to why I find a lot of papers so boring to read, difficult to recommend to non-academic colleagues and why so many of us just skip the intros and discussions!”

For scientists who do not speak English, committing to writing a paper in their first language still does not solve the issue. When writing the “introduction” of a research paper, scientists are expected to conduct a thorough review of existing literature and explain how their research builds on this. Without access to or understanding of English language papers — which make up the majority of existing science literature — this can be tricky.

Academic culture

Finally, there is the less-discussed issue of academic culture. In many countries in the global south, academia is less of a priority than in the global north, Schipper tells Carbon Brief: “In a lot of global-south universities, most of the task is to teach and there’s not as much emphasis on research because research funding is not available as much… Because the salaries are so bad, they often take on a lot of consulting work — like UNDP or other kinds of organisations — so they don’t really have time to do research. They do other kinds of work to supplement their incomes.”

When the Reuters “hot” list was published, it triggered a backlash across the climate science community for its lack of diversity. Schipper tells Carbon Brief that a serious issue with the list is its presentation of the scientists as the most “influential” in climate science. This “influence” is calculated using a western approach and does not take into consideration the different roles of climate scientists in developing countries, she tells Carbon Brief. She adds: “I would even argue that a lot of global-south scholars might have a much better relationship with policymakers because there’s fewer of them. The policymakers are looking for scientific advice…So if you spend seven days every month working with your minister of environment, or sitting in meetings at the ministry, then you’re not writing a paper, but also you might have a much stronger influence on what happens.”

This is an example of how a northern approach to quantifying academic performance can underestimate or miss out contributions from the global south.

The gender gap

In addition to the north-south divide, there is a well-documented gender bias in academic publishing. Carbon Brief’s analysis finds that only 22 per cent of authors from the Top 100 most-cited climate science papers over 2016-20 are female.

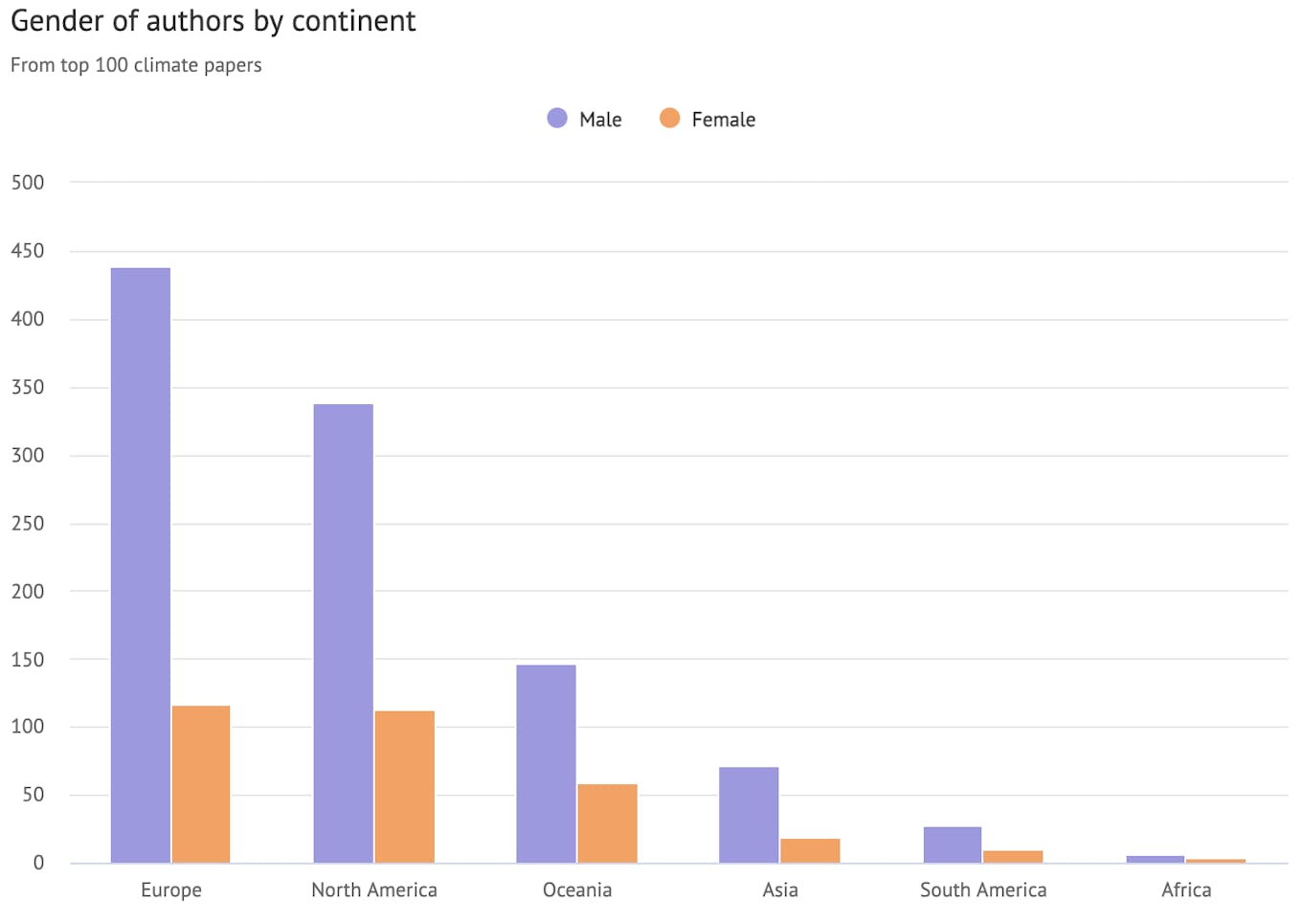

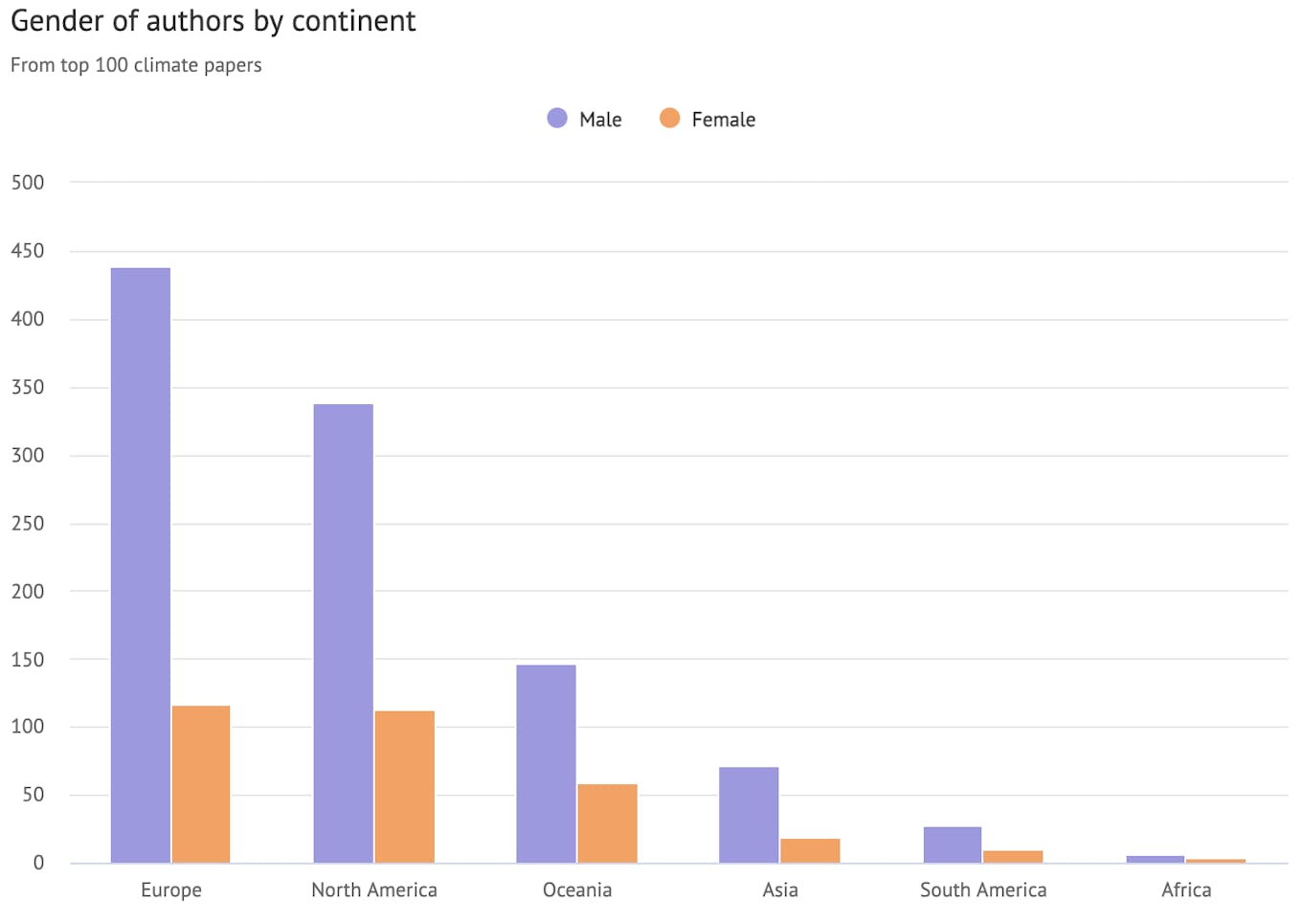

The plot below shows the number of male (purple) and female (orange) authors in this analysis from each continent.

The number of male (purple) and female (orange) authors in the Top 100 most-cited climate science papers during 2016-20, shown by continent. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Female authors account for less than half of the total authors in every continent analysed in this study. In Europe, North America, Oceania and Asia, the total percentage of female authors is 20 per cent, 35 per cent, 29 per cent and 23 per cent, respectively.

Past research has suggested that publication rates for women are lower in developing countries. However, percentages for Africa and South America are not given here, as the total number of authors from these continents is low. More data would be needed to confirm this.

The gender imbalance becomes more evident when focusing on lead authors — as women make up only 12 of the 100 lead authors in this analysis. Similarly, another study on first-author gender biases in the geosciences, found that female lead authors represent between 13-30 per cent of all first authors in the papers tested.

Barriers to female scientists

Women in STEM

An obvious explanation for the low level of female authorship in climate-science papers is the low proportion of women in science. Fewer than 30 per cent of the world’s scientific researchers are women, and the tendency of women to leave academia sooner than their male counterparts — known as the “leaky pipeline” — means that female academics are less likely to reach senior positions.

The leaky pipeline is, in part, due to the inflexibility of academica, Schipper tells Carbon Brief: “The clear thing is this leaky pipeline where women — and also often anybody who’s not a white, cis man — tend to ‘fall out’ because of all because barriers that are in the system — and lack of flexibility is one of the biggest ones.”

Progress is being made in improving the gender balance of women in science within some countries and sectors. However, there are still barriers facing women within the world of academia — driven in part by stereotypes and unconscious biases.

There is extensive literature disproving the misconceptions and stereotypes about women in science — such as “women are worse at maths” and “women are not analytical enough for science”. However, despite having been proven untrue time and time again, these assertions — introduced to girls at a young age — can affect their performance and confidence.

Pathak tells Carbon Brief that from an early age she was exposed to stereotypes about the ability of women in science compared to that of men. “They just don’t think you can think. They don’t think you are intelligent,” Armenteras adds.

Upon reaching the male-dominated field of scientific academia, the environment can be hostile for women, who are judged more harshly, earn less money, are less likely to have their work cited and face a “motherhood penalty” long before they actually have children. Women are then more likely to leave academia upon having their first child than their male counterparts.

Women who choose a scientific career path are less likely to choose natural sciences — such as maths, physics and engineering — than social sciences. This also has implications for the gender balance in climate-science research, Schipper and Pathak pointed out in their response to the Reuters Hot List: “Natural sciences receive 770 per cent more research funding on climate change than social sciences, which generates large differences in the sort of publications being produced. Related to this, gender biases in funding are significantly more explicit in the physical sciences than in social sciences and there are more men in STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] subjects than women.”

Schipper points out that “traditionally, STEM subjects like physics where you would learn to model are overwhelmingly male”. She adds that climate-modelling studies are typically published in higher-impact journals, and are often faster to write and publish than social science papers, allowing authors in this field to accumulate more publications and citations.

Pathak tells Carbon Brief: “You’ll see a lot of [quantitative] climate-science papers attracting more citations. But there’s also this very important branch of social and behavioural science where the journals are not often that highly ranked and, therefore, sometimes women who are not in those quantitative fields get underrepresented. I have colleagues in the social sciences who don’t even get a fraction of the funding that [more technical] science gets.”

The dominance of “economics-and engineering-based” backgrounds within climate science is highlighted in a 2015 study, which analyses the authorship of the working group III part of the fifth assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). It found that 56 per cent of the authors analysed had an economics or engineering background, while social scientists represented 22 per cent of the authors and humanities only 2 per cent.

Meanwhile, a survey of more than 100 female authors of IPCC reports found that “41 per cent of women saw gender as a barrier to their success, and 43 per cent believed that female climate researchers are not well represented in the climate community”.

The dominance of “economics-and engineering-based” backgrounds within climate science is highlighted in a 2015 study, which analyses the authorship of the working group III part of the fifth assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). It found that 56 per cent of the authors analysed had an economics or engineering background, while social scientists represented 22 per cent of the authors and humanities only 2 per cent.

Meanwhile, a survey of more than 100 female authors of IPCC reports found that “41 per cent of women saw gender as a barrier to their success, and 43 per cent believed that female climate researchers are not well represented in the climate community”.

Cultural norms and gender roles

Cultural norms and gender roles play a notable part in the experiences of women entering academia.

There is sometimes an expectation that academics need to work beyond the typical 9-5 hours kept in many other professions. However, women are traditionally the care-givers for young and elderly relatives and tend to take on more household responsibilities than their partners, which takes up their time and energy.

Chitsamatanga tells Carbon Brief that her schedule is “hectic” and leaves limited time for her work as an academic: “My day begins at 4:30am getting the kids ready to go to school. By 3:30pm I have to rush back home to collect the kids and we have to start preparing for tomorrow. There’s laundry to do. There’s cooking to do… The duty of being a mom, of being a wife, of being a daughter-in-law comes first…in most cases, when you get home, you have to train yourself to say ‘when the kids go to bed, then I will try and do one hour or two hours of work’.”

Chitsamatanga says that female academics in Africa have to “put on a lot of hats” and juggle their limited time between many different responsibilities. However, this is usually not the case for men, she adds: “It’s an issue of tradition and cultural beliefs and the way that you are brought up. For African men, it’s easier to say, ‘I don’t want to be disturbed’. We have been brought up to give them that space. Then you [women] have to make sure that you are keeping the kids quiet, you’re entertaining them. But, if it’s me that has a deadline, I have to find a way to meet it, even if it means I just have to spend that whole night working… We have to stretch that 24-hour day to 72 hours.”

She also tells Carbon Brief about cultural and traditional beliefs in Africa that require women to refrain from loudly voicing their opinions or challenging others. This can prevent female academics from putting themselves forward, for fear that they will be called “wayward”, Chitsamatanga says. There are also potential issues in interactions between male and female academics, she adds: “There are few male academics that want to mentor female academics. There is the insinuation that if the two people are working closely together, then there must be something going on between the two of them — that kind of thing. The female academics themselves tend to be uncomfortable at being mentored by a male.”

Armenteras also notes the danger of appearing “bossy” or “overbearing” as a woman in science trying to make their case. And Mwampamba tells Carbon Brief that she often enjoys the atmosphere when working with mostly women: “It’s usually less competitive. It’s just an environment that’s so much more pleasant to work with. I am usually consciously aware of how enjoyable and effortless it is and how everyone’s defensive barriers are mostly down. But when working with male academics I find myself turning on the ‘you are now working with men’ switch. Basically mentally and emotionally preparing myself to be ‘harder’, i.e., not to accept to be the note taker, to volunteer much less, to have to repeat my ideas several times, to be more stoic.”

However, even when there are no overt systems separating men and women, peoples’ perceptions and unconscious biases can still play a huge role in hindering women.

Armenteras tells Carbon Brief that “sexism is still in science everywhere”. For example, she describes discussions with colleagues in which her ideas were “dismissed many times”, but where the same ideas were accepted when proposed by a man.

“We women have so much information that we want to share — about our research, our work, our perspectives of the field we are contributing to,” Mwampamba says.

Women from the global south face (at least) two barriers — gender and race. This “intersectionality”, in which a single person faces multiple overlapping systems of discrimination, comes with its own challenges, Mwampamba adds: “You are never sure whether access to something is denied because of your colour, because of your gender, or because of your nationality. You’re always questioning that. And I think the opposite is true as well — you aren’t sure whether you were invited to something because they truly value your work or if they were trying to fulfill some diversity criteria.”

‘Decolonising’ academia

For many countries in the global north, the history of scientific progress is closely entangled with that of colonialism . This history is still clearly embedded in many aspects of science and academia. As such, there is a growing movement to “decolonise” academia, by working to recognise the colonial context of modern-day science and — as one article explains — to “eliminate, or at least mitigate, the disproportionate legacy of white European thought and culture in education”.

Biased science

Carbon Brief’s analysis shows that women and researchers from the global south are significantly underrepresented in climate-science literature.

Mwampamba tells Carbon Brief that the lack of diversity means we are “missing a whole set of brains that can contribute to science”, as well as ignoring the opportunity to try “a whole new type of science — a science that is a lot more inclusive of other ways of doing things, other ways of generating knowledge”.

She adds that important data is also being overlooked by limiting the scope of international science to English-language journals.

Demeter stresses that diversity increases the quality of science: “Diverse communities, including academic communities, can provide more creative work. Research shows that the contributions of diverse research groups are generally better than those of their less diverse counterparts.”

And Pathak emphasises that negotiations and decisions around climate action will need global contributions: “Climate change is a global problem. If we want wider participation in decision-making, we need to understand all the available solutions and which ones are going to be accepted. It is therefore important to get wider views — from indigenous communities, non-English speakers, communities who are never invited or consulted. We won’t know what local solutions are available if we never consult them.”

One study concludes that “the production of knowledge is biased towards richer regions with cooler climates”, noting that “the imbalanced production of knowledge affects adaptation and policymaking”.

Another states that the supply of knowledge is “biased toward the richer and less vulnerable countries”, while the production of knowledge is “is skewed away from the poorer, fragile and more vulnerable regions of the world”.

While science aims to be completely objective and free from bias, this is difficult to achieve. Science is conducted by individuals, each of whom bring their own biases to the way they conduct research, Schipper tells Carbon Brief: “It’s a fallacy to say that science is neutral and that we’re not influenced by other things in our lives. We [scientists] get our training and so on, but world views, perspectives that we have and our social cultural baggage influences the way that we understand what we’re looking at. And so it’s not that women or ethnic minorities or disabled researchers inherently or biologically do research differently — but it’s about the perspectives that we bring and the way that we understand the problem — particularly with climate change, because it is a societal problem.”

Dr Farhana Sultana is an associate professor at Syracuse University in the US. She also notes the skew in knowledge production when one group is over-represented in science, telling Carbon Brief: “Knowledge production and circulation are skewed and incomplete, and this distorts and impoverishes public discourse on important topics. Ultimately, this has deleterious consequences in policies and practice. [Our current system] ends up reproducing a knowledge system that is exclusionary and misses out not just a diversity of voices, but perpetuates the colonial practices of discounting of knowledge, lived experiences and wisdom from many global-south contexts.”

This is unsustainable, as reliance on “trickle-down science” leads to “ongoing reliance on the global north for solutions to local problems and an inability to develop alternative approaches to problem solving that take local — non-northern — contexts into account”, one study explains.

Demeter adds that as the entire system of knowledge production is skewed towards the interests of the global north, they can “determine the leading theories and ideas, the adaptive courses of actions and the accepted forms of academic capital in the world-system of knowledge production”.

He adds that higher education has “a few elite and a legion of communal institutions”— meaning that we only hear voices from the “international elite”. He tells Carbon Brief that to make their voices heard, underrepresented scientists often have to “repeat the knowledge disseminated by the ruling elite”. He adds: “If academics from the underprivileged peripheries succeed in reaching the centre, they have to sacrifice their authenticity. It is very hard to imagine a peripheral academic with a global reputation who lacks elite central education: they must be subjected to intellectual reeducation — a form of intellectual colonisation — before they are permitted to express their voices.”

Schipper stresses that, based on her experience, circumstance — rather than lack of knowledge — are holding back authors from developing countries: “There is a huge amount of fantastic knowledge coming out of the global south, but there are some really deep systemic issues that stand in the way and prevent authors from submitting published.”

Solutions

None of the academics who Carbon Brief spoke to say they are surprised with the overall findings of this analysis. All are well aware, they say, of the systemic inequalities within academic publishing.

Carbon Brief asked the scientists how they think diversity within academic publishing can be improved and the system of academia decolonised.

Earlier this year, Armenteras wrote a comment piece in Nature Ecology and Evolution outlining guidelines for “healthy global scientific collaborations”. In this piece, she explained how academics from the global north can collaborate with researchers from less-developed countries in a constructive way — including avoiding tokenism, building long-term collaborations and focusing on building capacity in developing countries rather than going in with an “extractive” mindset.

She tells Carbon Brief that, after publishing this article, she received many messages of agreement and support from other academics from the global south: “I got messages from many African countries, I think every single South America and Latin American country. We share a lot of sentiments.”

Armenteras tells Carbon Brief that, in order to make collaborations fairer, it is important to “get rid of your implicit bias” and “be aware that you are in a position of privilege” when working with local researchers from lower-income countries.

Meanwhile, the “manifesto for action” published by editors of the Climate and Development journal outlines further actions that can be taken to improve the representation in climate publishing.

The manifesto states that scholars must “actively cite” female scholars and researchers from the global south, cite across disciplines and actively seek out co-authors from the global south.

Chitsamatanga stresses that mentorship is crucial. It is particularly important for women, she says, so that knowledge about how to navigate academia as a woman is passed on down the generations rather than being lost. She adds: “Changes have been made and we are appreciative of those changes…I always say my main wish is for roundtable discussions, to get to know ‘what are your challenges, how best do we assist you, where are we going wrong and how best do we correct that?’”

For researchers in the global north, “not being inclusive certainly makes for a more efficient research process”, Mwampamba tells Carbon Brief. She acknowledges that limiting your collaborations to only those colleagues who are fluent in the same language, have good internet connection and live in the same time zone can streamline the process of research.

However, she emphasises the importance of diversity and of including researchers from the global south at all stages of the project. She tells Carbon Brief that researchers from the global north need to sit with their collaborators at the beginning of the project and work out what everyone expects and needs from the project.

“Design the whole thing together, apply for the grant together, then execute it together,” she emphasises.

“The country’s economic development is undoubtedly an important factor,” Vuong tells Carbon Brief. In a recent Nature “world view” article, he argues that investment in science is an important way of supporting countries’ development: “For a developing country like Vietnam that wishes to catch up with the developed world, the best way is to fully appreciate and strongly support the value of science as a foundation for technological advance.”

Demeter tells Carbon Brief that he wants to “confront the biasing effects of having elite degrees” by removing people’s institutional affiliations from submitted papers and other means of academic assessments, and having a person’s work judged based on “talent and production alone”.

He also outlines some actions that academics from the global south can take, such as organising regional conferences in which local academics take centre stage, He adds: “Moreover, they [researchers from the global south] should cite the valuable papers of non-central scholars at least as frequently as they cite the works of central academics in their publications. Finally, and most importantly, they should preserve and even critically intensify their authentic voices even after they succeed in acquiring positions in some of the central strongholds of the global academy.”

Increasing diversity among editors and peer reviewers can also have a positive trickle-down impact. Women and scientists from the global south are currently under-represented in editor and reviewer roles, but one study finds that “mixed-gender gatekeeper teams lead to more equitable peer review outcomes”. It also finds that for many countries’ papers were more likely to be accepted when their paper was presented to a “gatekeeper” from their country.

Adame tells Carbon Brief that she has started taken action and been pleasantly surprised at the response: “I have started pointing out to journals when I get a paper that is obviously parachute science, and leave a polite suggestion to the authors to include a local person. I have been surprised that the editor and other reviewers have supported me on this.”

Methodology

For this analysis, Carbon Brief used Google scholar metrics to rank the Top 100 English-language journals, based on citation number, over 2016-20. From the 100 journals listed by Google scholar metrics, Carbon Brief selected all journals that could contain climate-science papers, excluding (for example) medical journals, such as the Lancet.

Google scholar metrics ranks every paper published in its selected journals over 2016-20 by citation number. Carbon Brief used this ranking to manually select the Top 100 climate science papers from the selected journals.

Papers about energy and air pollution are not included under the umbrella of “climate science” for the purpose of this analysis. Policy forum pieces from Science and Science Advances have been excluded. Comment pieces from Nature journals have also been excluded, as these are written on an invitation-only basis.

For every paper, each author’s gender and country of affiliation was recorded. Country of affiliation is based on the author’s institutional affiliation in the paper. For authors with multiple affiliations, the first listed affiliation was used.

(Approximately 20 of the authors in this analysis are affiliated with institutions in both the global north and global south. Around two thirds of these authors had their affiliation from the global north listed first on their papers, with the remaining third listing their global south affiliation first. As there are more than 1,300 authors in the analysis, this unequal split does not materially affect the results.)

For papers with joint lead authorship, the first listed author is identified as the sole lead author in this analysis. However, Carbon Brief notes that the convention for selecting first authors varies across fields, and may mean different things across the different papers in this analysis.

The gender of authors is based on the usual gender of their first name as determined by genderise.io (a web-based API), an internet search for their professional website bearing a sex-specific pronoun, author appearance from images or by asking the author over email.

The use of the genderise.io API to determine the gender of individuals has been used in research articles (see examples here, here and here) and by publications including the Guardian. The use of internet searches and appearance based on images has also been used in research articles (see examples here and here).

If genderise.io could not predict the gender of the author with at least a 90 per cent probability and all other methods failed, the author is included in country analysis, but excluded from gender analysis. This is the case for 13 of the authors, accounting for less than 1 per cent of the total analysis.

Carbon Brief recognises that gender is not best categorised using a binary “male” or “female” label, and appreciates that the methods used of determining author gender could result in inaccuracies. However, for the purpose of this analysis, this method was deemed the most suitable.

(Carbon Brief also “scaled” the results so that each paper was given an equal weighting. This was to avoid single papers with tens of authors from the same country skewing the results. However, the scaling did not notably change the results of the analysis, so the results are not presented in this piece. However, these results can be found in the data.)

As the results were recorded manually, Carbon Brief acknowledges the possibility of human error. A large sample size of more than 1,300 authors was employed to try to mitigate the effect of any such inaccuracies on the final results.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.