The last decade was pivotal for the world’s forests. The 2010s saw the rise of unprecedented new commitments — from governments and the private sector alike — to bring deforestation to heel. The UN REDD+ framework, the New York Declaration on Forests and the Sustainable Development Goals set out ambitious targets to conserve and restore millions of hectares of forests.

But as this decade ends and a new one begins, it is also clear the world has fallen short on achieving its forest goals. While the impacts of climate change are being felt around the world, forests — an invaluable climate mitigation tool — are still being lost at high rates. Leaders in key countries are back-tracking on forest protection.

All of this has shaped the forest landscape today and will propel the world into an uncertain new era. Here, WRI’s forest experts reflect on 10 major changes for forests from the last decade, and what we should expect in 2020 and beyond.

1. Global primary forest loss remained high

By Mikaela Weisse

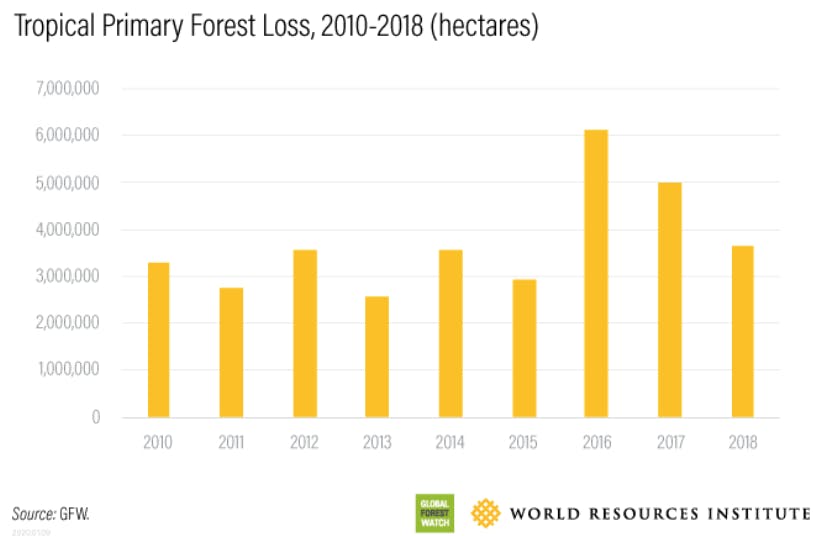

Despite international efforts, the loss of tropical primary forests persisted over the past decade. The three most recent years with available data (2016, 2017 and 2018) experienced the three highest rates of primary forest loss since the turn of the century. Primary forest loss saw a notable spike in 2016 and 2017, mainly linked to fires in the Brazilian Amazon, which made international headlines again in 2019.

While the rate of primary forest loss today is similar to that of 2010, what has changed is the relative contribution of different countries. For example, Indonesia reduced its primary forest loss by 37 per cent between 2010 and 2018, at least in part due to government policies – though some of that achievement may be overshadowed by another strong fire season in late 2019.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the other hand, nearly doubled its rate of primary forest loss between 2010 and 2018. The country is now second only to Brazil in amount of primary forest lost annually. Colombia has likewise seen a doubling of its primary forest loss.

The biggest question for the coming decade is if we will finally start to see evidence of efforts to reduce deforestation reflected in the tropical primary forest loss numbers. Global Forest Watch will continue to monitor and report on the latest changes.

2. New technologies made it easier to monitor forests…

By Rod Taylor

Innovations in remote sensing and cloud computing have made high-resolution global geospatial data available in user-friendly formats at low cost. It is now easier than ever to understand what is happening to forests and make informed decisions over their use and management. For example, Global Forest Watch, launched in 2014, made the University of Maryland’s tree cover change data freely accessible online in dynamic, easy-to-understand maps, charts and graphs.

Closer to the ground, drones, mobile phones and wireless sensor networks have made it easier to find and observe precise locations and ground-truth remote-sensing data. Advances in information technology, internet connectivity, GPS tracking systems and product scanning devices have been deployed to trace forest products and agricultural commodities throughout the supply chain, helping businesses responsibly source materials.

The coming decade offers the prospect of even more powerful technology. New satellites with radar and extremely high-resolution optical sensors will overcome cloud cover limitations and help reveal forms of ecosystem degradation that fall short of outright forest loss. NASA’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) will help map biomass and forest structure from space, enabling more sophisticated approaches to quantifying forest carbon.

New data-mining technologies such as natural language processing and web scraping offer the prospect of faster and stronger policy analysis, and a greater ability to understand the political and social economy around forests. Increased cloud computing power, coupled with new machine learning techniques like spectral clustering, should speed up image processing and augment what we can learn from remote-sensing data.

3. …but biodiversity monitoring technology lagged behind

By Laura Vary

Common and beloved species have been disappearing at 100 times the natural background rate, with massive decreases in species ranging from roadside insects to songbirds to lemurs. But despite growing concern, our ability to monitor these changes and measure biodiversity losses consistently in time and space remain elusive.

The kind of technological innovation that allowed near-real time forest monitoring has yet to arrive for biodiversity monitoring. At the beginning of the decade, we were excited by the potential of field DNA scanners that could identify any species in minutes and remote sensing that could make comprehensive species maps. These new technologies promised a more precise understanding of species ranges, early detection of at-risk species and possible drivers of extinctions.

With these promises on the horizon, companies and governments made commitments to prevent biodiversity losses and report on their progress. Yet the technology developed too slowly to measure progress towards these commitments, only now becoming available for certain species or regions of the world. Without the right tools for the job, policies for protecting biodiversity have focused on increasing protected areas as a broad-brush solution despite their known limitations.

Though forest protection and conservation remain important policies for preventing biodiversity losses, we need to be able to measure biodiversity directly. In the coming decade, the technologies promised may finally be ready to help slow the pace of extinction and protect our planet’s biodiversity.

4. Climate change battered forest ecosystems

By Fred Stolle

Forests are a critical buffer against climate change, absorbing one third of the carbon we emit every year, maintaining stable rainfall patterns and moderating extreme temperatures. This climate guardian has been overtaxed over the past 10 years and is now suffering the consequences of a warming world.

Fires have scorched degraded tropical forests in Brazil and Indonesia, while temperate and boreal forests have seen unprecedented forest fire regimes, from the pristine forests of Alaska to the densely populated foothills of California. Warmer, drier conditions have also allowed insect species like the pine beetle to ravage large tracts of forest in Canada and the United States, while drought has weakened trees in Germany, causing a mass die off.

Sea level rise is threatening mangrove forests— an incredibly carbon-rich forest ecosystem that prevents shoreline erosion and houses a diversity of marine species. The extent of mangroves is already declining in arid coastal areas like Australia and along rivers in the Caribbean and Indo-Pacific region.

If we want to mitigate climate change impacts on both local and global scales over the next decade, we must protect primary forests, reduce forest loss, increase tree cover and limit human-caused disturbances. Only then can forests keep delivering the climate services we need.

5. Forests and people became increasingly intertwined

By Nancy Harris

There are 800 million more people on the planet than a decade ago, and growing demands for food, fuel and fiber have triggered dramatic changes to forests worldwide. In the tropics, primary forests continue to decline. Secondary forests recovering from past clearing are now prominent features of tropical landscapes; many are integrated into forest-agriculture mosaics that sustain 200-300 million people. Land covered by forest plantations is at a historical high, while urban forests improve quality of life in cities where over half of the world’s population lives. The boundary between forests and human development has never been more muddled.

Even after decades of recovery, degraded forests have lower carbon stocks and less diverse species compositions than primary forests. What are our options? Returning forests to their full historical extent is a near impossibility, but this does not mean we should accept future changes as inevitable. In many regions the last chance to protect intact forests is now, and this should be our first line of defense.

Elsewhere, sustainable management of secondary forests, plantations and trees in agricultural and urban landscapes will be vital. These systems can relieve pressure on remaining primary forests while expanding rural economies, improving human health, regulating storm surges and reducing the urban heat island effect.

In the coming decade, we must work towards a world where forests and trees are recognized as much for the ecological services they provide as they are for wood production or new farmland and the burden of responsibility for protecting forests extends to everyone.

6. REDD+ experienced a renaissance despite a rocky start

By Frances Seymour

A global agreement on forest conservation has been elusive since negotiations collapsed in the run-up to the 1992 Rio Earth Summit. The broad consensus on REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation, plus conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks), a UN framework finalised in 2013 in which industrialised countries provide developing countries financial incentives for protecting and sustainably managing forests, is one of the most significant achievements of the last decade.

Initial enthusiasm for REDD+ waned without the large-scale finance expected to materialize from the global carbon market, and public finance proved slow to disburse. Early critics cited the poor performance of project-scale initiatives, even though REDD+ was designed for implementation at the national or subnational level.

Nevertheless, the initial burst of excitement over REDD+ continued to ripple through dozens of developing countries over the course of the decade. Countries, states and provinces made real progress toward establishing the forest monitoring systems, reference emission levels, action plans and safeguard systems necessary to reduce forest loss and become eligible for results-based payments.

Now, at the close of the decade, REDD+ is experiencing a renaissance. Over the last year, there has been an uptick in the number of payment-for-performance agreements signed (by entities such as the FCPF Carbon Fund and the Green Climate Fund, as well as a new bilateral agreement between Norway and Gabon), new standards under development (such as TREES), and new prospects of private sector finance (such as under ICAO CORSIA).

New science has focused attention on the mitigation potential of “nature-based solutions” to climate change, for which forest protection and restoration are paramount. In the coming years, expect more finance to be directed to REDD+ and higher prices per ton of avoided emissions. Together, these incentives will finally test the proposition that material rewards will lead governments to prioritise forests.

7. Commodities became “de-commodified”

By Luiz Amaral

Throughout the 20th century, many food ingredients have largely been traded in bulk, without any differentiation, and commercialized according to global prices. But the last decade saw the beginning of the “de-commodification” of commodities markets. In other words, once homogenous products are now being differentiated according to how they were produced, due in large part to consumer demand.

The 2010’s saw a growth in certification. For example, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil was founded in 2004, but 98 per cent of all palm oil certifications happened in the past 10 years. Global multi-stakeholder initiatives like the UN’s New York Declaration of forest, Consumers Goods Forum, and TFA2020 were also launched with strong commitments to eliminate deforestation from agricultural supply chains. In practice, this means differentiating two otherwise equal products into “acceptable” or “not.”

There are limitations to this revolution. Commitments have not yet delivered their promised impacts and are still mostly limited to richer consumer markets. Alone they will not solve the global food challenge while protecting forests, but the trend can be expected to intensify in the next 10 years.

Desire for deforestation-free products may have sparked this trend, but it will not stop there. Other sustainability and ethical concerns like farm income, food safety and even quality and taste of a product will further fracture homogenized markets.

The remaining question for the next decade is: Will this be a slow-moving trend or completely disruptive? The answer will depend on technology’s capacity to reduce the transaction costs enough to allow differentiated items to fully compete with standardized commodity markets.

8. Restoration pledges proliferated, but action was insufficient

By Sean DeWitt

In response to widespread deforestation and land degradation across the world, countries and NGOs came together in 2011 to launch the Bonn Challenge, an effort to restore farms, forests and pasture by 2020. The New York Declaration on Forests strengthened that resolve.

Over the next eight years, 62 countries committed to make more than 170 million hectares of degraded land economically and ecologically productive again, mostly through country-led partnerships like AFR100 in Africa, Initiative 20×20 in Latin America and ECCA30 in Europe and Central Asia. Impact investors and technical partners jumped in too, pledging billions of dollars to restore landscapes as countries began to shift policies.

But deforestation continues to expand quickly. Between 2014 and 2018, the world lost another 120 million hectares of tree cover, an area larger than Colombia, while only about 30 million hectares of land is under restoration, according to self-reported data from countries.

Although deforestation still outpaces restoration, there is hope. A better understanding of how restoration contributes to rural development, healthier ecosystems and climate change mitigation has spurred countries and companies into action.

Large multinationals are investing in restoration while countries like Malawi are funding programs that employ young people to restore land. In Ecuador, impact investors like 12Tree work with farmers to build profitable businesses that protect and restore forests. This trend is apparent across the globe, as we are beginning to accurately track progress, especially where it directly benefits rural communities.

What comes next? The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration begins in 2021. Better local planning is needed, especially in landscapes where forest protection, sustainable agriculture and restoration are all essential. We need to support communities and entrepreneurs to grow trees and help smallholder farmers. And we need to show that restoration works and accelerate its impact.

9. Indigenous peoples asserted their rorest rights

By Jessica Webb

Indigenous peoples and local communities inhabit more than 50 per cent of the world’s land, and manage at least 17 per cent of the carbon stored in forests. An expanding body of literature over these past 10 years provides evidence of the effectiveness of indigenous communities as forest stewards, leading to greater recognition that global conservation and climate agendas cannot, and should not, progress without them.

The numbers speak for themselves. In the Amazon, deforestation rates (along with corresponding forest carbon emissions) are two to three times lower in legally recognised indigenous territories as compared to lands outside them.

The proliferation of cellular networks and smartphones have connected many historically isolated and remote communities to global audiences. Mobile apps designed to document evidence of environmental threats and human rights violations, map territories and facilitate social media sharing have enabled more collective action and social mobilisation.

But the elevated profile of indigenous peoples has also made them a target. Global Witness found that more than 1,700 environmental and land defenders have been killed so far this century, with an average of more than three murdered each week in 2018. About 25-40 per cent are indigenous peoples, even though they make up only 5 per cent of the world’s population.

In 2020 and beyond, the role and visibility of indigenous peoples in achieving environmental goals will increase. The tide of public opinion is changing, with greater concern for the impacts that deforestation has on indigenous communities. We should also expect donor agencies, NGOs and international institutions to continue allocating resources to support indigenous interests. Indigenous youth activists will also play a bigger role in mobilizing the masses for climate action.

10. Political environmental leadership declined

By Chip Barber

The past decade saw the rise of populism in both developing and developed countries, and this was bad news for the world’s forests and those who seek to defend them.

Forests have suffered from populist efforts to delegitimise environmental science, demonize NGOs and limit access to information. Conserving forests and achieving sustainable development became more difficult in countries where political leaders trampled democratic freedoms, dismissed science or turned a blind eye to the rule of law.

At the same time, the multilateralism that enabled agreement on the UN conventions on Climate Change and Biological Diversity in 1992, as well as the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015, has progressively unraveled.

The lack of action at the December 2019 Madrid Climate meeting— largely due to the intransigence of leaders of large emitter countries like the US and Brazil — is the most visible and latest demonstration that many national leaders are disconnected from the demands of their citizens. The Biodiversity treaty and other forest-related UN initiatives are almost invisible to the public (Does anyone even know that there is a “UN Strategic Plan on Forests”?) and have little real-world effect on forests.

World leadership is faltering on global environmental issues. Although corporations and NGOs are making efforts to guide us out of this environmental wilderness, the evidence of the last decade shows that well-meaning CEOs or data platforms are no complete substitute for the power and authority of governments. Perhaps the rising generation of activists can help us change direction.

But in the coming decades and beyond, all of us will need to reorient ourselves to be more than just “consumers” or “voters”. We must once again become citizens pushing our leaders for the change we want to see.

A new decade for the world’s forests

As we enter into a new decade, we take the successes and failures of the previous one with us. Renewed leadership, continual technological advancement and the all-important contributions from individuals dedicated to protecting their livelihoods and their natural heritage will prove critical for the years to come.

This post is republished from the WRI blog.