When the financial crisis of 2008 struck, it left in its wake devastated economies and a general distrust of financial markets and the institutions meant to hold the industry to account.

So when a shiny new cryptocurrency named Bitcoin emerged later that same year, promising transparency, incorruptibility and freedom from middlemen such as banks and traders in transacting, there was hope that it would revolutionise the global financial system.

Ten years later, Bitcoin hasn’t come close to replacing money, but the underlying data storage technology it was based on, known as blockchain, is making waves in the field of sustainability. Blockchain has been applied to supply chains to trace the origins of seafood, and to turn plastic waste into a source of income for the poor.

But what is it?

Simply put, blockchain is a public chain of records in which each new transaction is logged. All parties who have access to the blockchain will have the same copy of the record, which is updated each time a new transaction is made and collectively verified.

Blockchains are used as an open database or a distributed ledger system for its most obvious and appealing qualities: transparency, immutability, consensus-building and traceability.

For example, imagine you’re shopping for a pair of denim jeans at a store. By scanning a QR code on the clothing’s tag with a smartphone, you can see exactly when the cotton was harvested, the amount of water used to produce it, and where the denim was cut and sewn. Blockchain can offer customers a remarkable level of insight into a product’s manufacturing and supply chain. In fact, it’s already being done.

“Blockchain is a revolutionary step in data processing and data storage. It is a great solution if you have an issue with transparency, traceability and immutability,” says Laszlo Giricz, founder and chief executive officer of Poseidon, a non-profit using blockchain for forest conservation.

Blockchain and carbon

As the blockchain industry grows, so too has the excitement around its potential to help deliver more environmentally friendly ways of living and working.

From making sustainability reporting less painful to swapping clean energy between neighbours and unlocking climate finance, it would appear the only limit is creativity.

One big potential use for blockchain is in the carbon markets emerging around the world, where the sheer volume of trades and complex network of players—including producers, certifying bodies, middlemen and traders—creates room for manipulation and fraud.

“Carbon markets today are opaque because people do not have visibility as to where the carbon credits come from or go, which has led to double counting and fraud,” says Jeffery Liu Xun, co-founder of Xarbon Sustainability.

To address this, the Hong Kong-based blockchain company has created a cryptocurrency from carbon credits generated through the environmentally friendly projects it runs, such as forest conservation in Papua New Guinea. These digitised carbon units, called OCO, are sold to companies and individuals who want to either trade in global carbon markets or offset their carbon footprint, adds Liu.

Because the cryptocurrency sits on blockchain’s open ledger technology, buyers can see how many hands each unit has passed through, and trace it all the way back to the source. This gives companies and individuals the confidence that the credits they acquire are genuine.

From the Papua New Guinea rainforest conservation project, Xarbon has been able to accumulate 200 million tonnes in carbon credits that will eventually be sold on the carbon market, and is equivalent to conserving of 500,000 hectares of rainforest area. To put things in perspective, Singapore’s annual carbon footprint totals 206.5 million tonnes.

“

The fact that we can transact carbon credits in grams rather than tonnes is rather revolutionary.

Laszlo Giricz, founder, Poseidon

Another benefit of blockchain technology is that large units of carbon can be broken down into smaller units for offsetting, says Laszlo Giricz, founder and chief executive officer of Poseidon.

The company collaborates with retailers to get consumers to offset their purchasers with its OCEAN tokens, each of which represent a small amount of carbon. In May this year, it ran a pilot programme at a Ben & Jerry’s ice cream store in London, where customers had the option to offset the carbon footprint of their dessert. Within three weeks, the company had raised enough funds to protect forest area equivalent to 77 tennis courts.

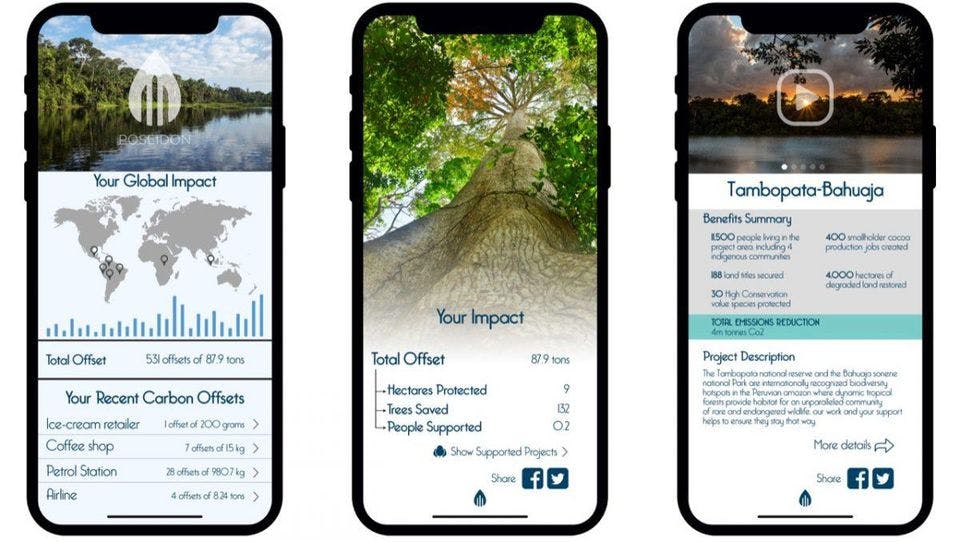

The company provides users of its app with details about the origin of their purchased carbon credits and the impact they are having. Image: Poseidon Foundation

“The fact that we can transact carbon credits in grams rather than tonnes is rather revolutionary,” Giricz remarks, adding that he hopes micro transactions like that would become as addictive as a “super drug”.

He says: “People use drugs is because of the immediate feedback. By offsetting purchases based on blockchain solution, within seconds you can see the impact of your giving.”

Beyond carbon

In the energy sector, blockchains are enabling peer-to-peer transactions with the help of smart contracts.

Shanghai-based Energo Labs uses this combination to create a community-based clean energy trading system. Households with solar panels and smart meters can sell excess energy as Watt tokens by putting up a sales order through the company’s mobile app.

The system’s smart contract, which operates on blockchain techology, automatically matches the sales order to purchase orders created by other users, and completes the transaction without the need for human intervention.

“We want to create a network where people can easily upload and download excess renewable energy, as easy as downloading MP3 music on our devices,” remarks Kai Kai Yang, chief operating officer of Energo Labs.

The company last year established a successful pilot microgrid system at the De La Salle University in the Philippines. Combined with other energy conservation initiatives on campus, the project is set to save the university 1.2 million Philippines pesos (US$22,254) over the course of its 20-year lifespan.

Blockchain is shaking up the food industry as well. Californian firm Pavo helps farmers sell organic food produce directly to consumers with the aid of blockchain-based smart contracts.

By using the blockchain platform to certify products are grown organically, Pavo hopes to ease the costs that farmers bear for certification. Instead, farmers can assure buyers of the quality of their produce by showing them crop data. Smart meters also reduce the need for middlemen, ultimately making organic food cheaper for consumers.

Co-founder and chief executive officer, Erhan Cakmak, explains: “We aim to make farming cashless and frictionless, devoid of complicated authorisation procedures. These problems can easily be solved using [blockchain] technology.”

With new tech comes new risks

But blockchain alone will not cure the social and environmental evils of the age, say blockchain experts.

“I’m increasingly concerned that many think blockchain is the holy grail that will solve everything,” remarks Giricz.

Blockchain isn’t without its weaknesses. Experts have said that although immutable once inside the system, data that is entered into the blockchain has to be first verified in the real world, which will take effort and resources.

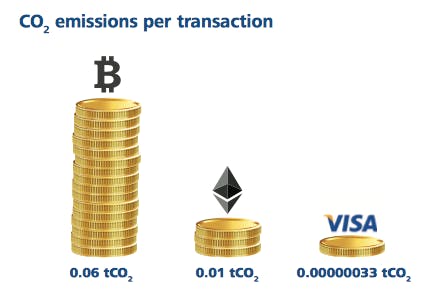

Cryptocurrencies representing different types of blockchain. Image: QuoteInspector, CC BY-ND 2.0

According to Deanna Macdonald chief executive officer of BLOC, an open collaboration platform using blockchain, at Asia Pacific Climate Week in July: “[Blockchain] is a great mechanism for creating a chain of custody but the technology still relies upon intermediaries.”

This means that while the blockchain prevents people from tampering with records, it can not prevent erroneous or corrupt data from being recorded, say blockchain experts. And since the data has to be checked manually, it leaves room for human mistakes and manipulation.

Another complication is that there are many types of blockchain, each taking a different approach to the same end goal of efficient data storage. The major limitation in this is the lack of interoperability that restricts consumers and traders to exchanging goods and services with only those who are on the same blockchain.

Macdonald says: “What the technical community needs to achieve is interoperability, to make sure these blockchain systems can speak to each other, before we can get to a global scale.”

This means that, ironically, intermediaries have to be used in order to transfer value or information from one blockchain to the other.

Ultimately, blockchain cannot force people to behave in a way that benefits the environment and each other.

Liu remarks: “When people talk about blockchain projects to fight climate change, it is not simply about the technology but [getting] the whole ecosystem including community, incentives and regulators [into alignment].”

Macdonald comments: “All the elements [to fight climate change] don’t have much to do with blockchain at all.” What the technology can do is provide opportunities for consumers, retailers and producers to choose practices that are sustainable, but the onus remains on people themselves, she adds.

Is blockchain sustainable?

But there has been a lot of criticism surrounding blockchain’s shockingly big energy footprint, specifically for cryptocurrency Bitcoin.

The rate of transactions determines the energy efficiency of the blockchain, and therefore its carbon footprint.

A decentralised public ledger like Bitcoin requires hundreds of thousands of computers to constantly verify and log new transactions, causing its energy consumption to skyrocket, according to Andy Tan, who runs a Singapore-based blockchain start-up called Carbon Grid Protocol that helps blockchain projects offset their carbon footprint.

To give an idea of the amount of energy in question, a single transaction via a traditional system like Visa uses 180,000 times less electricity than if it were done through Bitcoin.

Comparison of carbon emissions per transaction for Bitcoin, Ethereum and Visa. Image: CleanCoin

The most obvious way for blockchains to slash their electricity consumption is for them to run on renewable energy. But given that an immediate switch to renewable energy worldwide is impossible, many believe that an easier alternative is to reduce the amount of computing necessary to verify blockchain transactions, therefore lessening its energy consumption.

That means, instead of using a computer-heavy mining process called ‘proof-of-work’ companies can ascertain data storage through less energy-hungry method called ‘proof-of-stake’.

Most non-mineable cryptocurrencies, including Ethereum, run on the proof-of-stake model and are significantly more energy efficient than mineable bitcoin cryptocurrency, but are significantly less popular, holding less than 30 per cent of the blockchain’s total market value.

This is still far from enough. To compete with the likes of Visa, Ethereum will need to become more than 30,000 times more efficient.

A more immediate solution is to offset the carbon emissions from blockchain’s energy consumption. Carbon Grid Protocol’s Tan believes that integrating offset options into blockchain platforms can help projects and companies based on different blockchain platforms to calculate their carbon impact and supply them with verifiable carbon credits to offset it.

He adds: “As more people find market solutions using blockchains, the ecosystem will grow and the requirement to create an offset mechanism will grow even further.”