Mentions of climate change and low-carbon energy have roughly tripled in annual reports from Chevron, ExxonMobil, BP and Shell over the past decade.

But even as these firms issue pledges to cut emissions and invest in renewables, the study concludes that such a transition is simply “not occurring” as all four companies continue to focus primarily on producing fossil fuels.

The study, published in PLOS ONE, comes in the wake of record profits for the fossil fuel industry as the global energy crisis bumps up oil-and-gas prices. In the UK, BP has argued against an additional “windfall tax” in response to the crisis, partly on the basis that it would hamper the firm’s planned low-carbon investments.

However, having analysed how the four companies’ commitments align with their climate action and spending, the authors of the new study question the extent of these investments.

While their oil-and-gas production has remained consistently high, less than 1 per cent of their capital investment went into low-carbon technology between 2010-2018, the study concludes.

An expert who was not involved in the new research tells Carbon Brief that it provides “robust” evidence that fossil fuel companies are “not walking the talk when it comes to addressing climate change”.

Major emitters

Due to the use of their products, Chevron, ExxonMobil, BP and Shell are associated with globally significant shares of greenhouse gas emissions. By one estimate, they are responsible for more than one-tenth of all CO2 that has been emitted since 1965.

State-owned companies based in China and Saudi Arabia are larger, but these four US and European energy majors are the biggest among investor-owned oil-and-gas firms.

Amid growing societal and political pressure these companies have started pledging to cut emissions, even committing to “net-zero” emissions targets – although in some cases only for their operations rather than their products. BP has said it intends to move away from oil to become an “integrated energy company”.

However, previous studies have extensively documented how oil majors have spread misinformation about climate change, spent millions lobbying against climate measures and shifted the blame for global warming onto consumers.

This historical behaviour suggests that the authenticity of the companies’ climate commitments “should be examined critically and exhaustively”, the researchers write in their new study.

Increasing trend

Mei Li of Tohoku University, along with co-authors Prof Gregory Trencher of Kyoto University and Prof Jusen Asuka of Tohoku University, set out to investigate the sincerity of the four oil-and-gas majors by analysing language employed in company documents and comparing it to the reality of their real-world activities and investment portfolios.

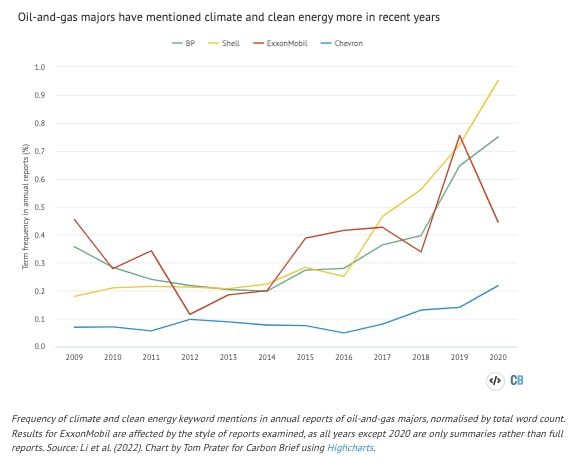

The first part of their analysis involved counting the number of times 39 key words or phrases, including “net-zero” and “low-carbon”, were mentioned in annual reports up to the most recent ones published in 2021, covering the period 2009-2020.

The frequency was then divided by the total word count in each report, providing a “rough proxy for the degree of awareness and importance placed on these issues”.

Annual reports were chosen because they were seen as the “most official and representative” of documents addressed to stakeholders and shareholders.

As shown in the chart below, the researchers found that the majors showed a “clear increasing trend” over the study period, adding that Chevron has the least noticeable increase and ExxonMobil’s results are hampered by the inconsistent format of its reports.

Prof Robert Brulle, a visiting professor at Brown University Institute for Environment and Society who studies the public image of fossil fuel companies but was not involved in this work, tells Carbon Brief that, while counting keywords is a simple technique for assessing the significance of a topic, “it is easy to understand and has face validity”, and therefore suits the researchers’ aims.

Pledges and actions

The second component of the research involved analysing pledges and actions relating to clean energy and decarbonisation made by each company.

To do this, the researchers identified 25 indicators of progress, ranging from simply acknowledging that burning fossil fuels causes climate change to scaling back oil and gas exploration.

Each indicator was assigned a score, with +1 indicating a pro-climate action activity, -1 indicating something that contradicts such activity, and 0 meaning no evidence of pledges or action in either direction.

The chart below shows each company’s total score over time. It shows that there has been a significant increase in companies pledging to address climate change towards the end of the decade, particularly the European majors, BP and Shell.

However, the study notes that when it comes to translating these pledges into reality, “the volume of concrete actions…is considerably less than pledges”.

This can be seen in the chart below, which shows that while the European majors still lead, the number of tangible actions taken has been relatively low. Often, the authors note that actions have contradicted pledges, giving the example of BP pledging to reduce fossil fuel investment in 2019 while increasing its area for new exploration access by 58,000 km2.

The study concludes that the companies have largely opted for “low-hanging fruit” in their business plans, including simple statements of support for climate science or carbon pricing. Every major has pledged to scale up its gas production.

The researchers also note that overall there has been “scant acknowledgement of the need to shift away from or reduce dependence on all types of non-sequestered fossil fuels…overall, statements consistently argue the reverse”.

A clean transition?

Finally, the researchers assessed the data communicated in annual reports to ascertain whether the figures supported the oil-and-gas firms’ climate rhetoric.

Among the metrics assessed were total earnings from fossil fuels and spending on fossil fuel acquisition, upgrading and maintenance. They found that while investment in exploration and production had peaked in 2013, analysis of relative spending showed that this remained the “pillar business for all majors”, particularly Chevron and ExxonMobil.

The researchers also looked at the average daily production of oil and gas, which has remained fairly constant for the past decade, albeit with the noticeable impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, and a significant dip for BP in the years following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

As well as fossil fuels, the researchers looked into spending on renewable energy and the amount of electricity these companies have generated from low-carbon sources.

They tell Carbon Brief that companies were “not at all” transparent about providing this data. Instead, the study authors turned to third-party sources, namely CDP and S&P Global Platts to get cumulative figures for the period from 2010 to the third quarter of 2018.

Overall, less than 1 per cent of capital expenditure across this period went towards low-carbon investments, they found. ExxonMobil and Chevron allocated the lowest share of their expenditures towards low-carbon energy – just 0.2 per cent each – while BP had surpassed the others with 2.3 per cent, followed by Shell with 1.3 per cent.

Oil-and-gas majors had also not generated significant amounts of power from clean sources over this period, according to the study.

Once again, BP was the best-performing of the four with 2 gigawatts (GW) of renewable capacity as of 2018 – the equivalent of two large gas power plants – while ExxonMobil had generated no clean power at all. The authors conclude:

“We find no evidence to suggest any major has entered the renewables market at a scale that would indicate a shift away from fossil fuels.”

The relatively low spending tallies with the conclusions of the International Energy Agency (IEA), which reported that 95.9 per cent of total oil-and-gas industry spending in 2021 was on fossil fuels, down slightly from 98.6 per cent the previous year.

A spokesperson from BP tells Carbon Brief that 2021 saw the company complete its “largest transformation” to deliver the net-zero strategy it set out the previous year:

“Because this paper looks back historically over the period 2009-2020, we don’t believe it will take these developments and our progress fully into account.”

Shell tells Carbon Brief that its target is to become a “net-zero emissions energy business by 2050, in step with society,” stating that its targets are consistent with the 1.5C target of the Paris Agreement.

A Chevron spokesperson says the company is “lowering the carbon intensity in our operations and seeking to grow lower carbon businesses along with our traditional business lines”, with $10bn of “lower-carbon investments” planned by 2028. ExxonMobil had not responded to a request for comment at the time of publication.

The authors acknowledge that there are more recent investments not accounted for in their analysis, estimating that low-carbon spending announced by BP and Shell in 2020 would amount to around 5 per cent of their capital expenditure that year. (BP tells Carbon Brief that in 2021 this proportion had increased to 12 per cent, with the ambition of 40 per cent going to its “transition growth businesses” by 2025.)

Study author Trencher tells Carbon Brief the companies’ announcements were still not clear about the “precise scope” of their investments and such figures “should thus be interpreted critically”. He adds:

“Even if there was evidence of more pledges, we urge stakeholders to recognise the difference between a pledge and a concrete action…and not to overlook the history of regressive actions we have documented over 12 years.”

Moreover, Prof Naomi Oreskes of Harvard University, who has researched climate communications by oil companies but was not involved in the new research, tells Carbon Brief that she finds the majors’ pledges inadequate:

“Instead of getting started on a transition when there was lots of time available, most of them engaged in strategies of denial and delay.”

‘Not walking the talk’

The authors conclude that while BP and Shell have shown more willingness to take climate action than their US counterparts, all four exhibit a “mismatch” between rhetoric and action.

An appraisal of their investments gave a picture that was even more “sharply misaligned” with the “increased green discourse”, they add. The authors therefore state that accusations of “greenwashing” levelled at these companies “appear well-founded”.

Brulle tells Carbon Brief the new paper is “original and robust analysis” that “goes well beyond the existing scholarship in this area by utilising a long time series analysis and robust empirical measures”. He adds:

“While activists have long asserted these claims, this empirical work by independent scholars empirically demonstrates that these claims are true. This is a major contribution to public knowledge of the actions of major oil companies and shows that they are indeed not walking the talk when it comes to addressing climate change.”

To match words with action, Trencher tells Carbon Brief the oil-and-gas majors should publish “a concrete roadmap of how fossil fuel production will be downscaled and then phased-out by mid-century and plan for the financial losses incurred on assets”.

He also recommends industry-wide criteria for what constitutes a “clean energy investment” and more consistent reporting on clean energy spending.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.