Even as organisers of the UN climate summit in Dubai, known as COP28, cheered a “breakthrough” agreement “transitioning away from fossil fuels” by 2050, critics were quick to point out a “litany of loopholes” in the legally non-binding agreement that will likely impede the furious progress required to slow global warming.

In light of this, and past UN voluntary accords, which can’t force any nation to act, environmental lawyers are stepping up their efforts to pressure policymakers and fossil fuel companies to drastically reduce emissions and support climate-vulnerable nations and peoples.

Dramatic courtroom victories in jurisdictions around the world offer some hope and have emboldened litigators to pursue legal action as a substitute for government or corporate climate action.

But while there is growing recognition that favorable judicial decisions are vital to curbing global warming, there is also an acknowledgement that litigators’ near-term ability to impact climate change and climate policy is limited, especially considering the long legal pipeline they must navigate.

“Litigation is very helpful, and there is a lot of it out there. But it’s misleading to think that it is going to be our big [climate action] savior,” Michael Gerrard, founder and faculty director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at New York City’s Columbia University, told Mongabay. “It’s a thing, but not the thing. We need a big toolbox.”

An oft-cited case in the Netherlands offers a prime example. In 2015, a Dutch environmental group, the Urgenda Foundation, and 900 Dutch citizens successfully sued the government to require it to reduce emissions, not by the 17 per cent it pledged in that year’s Paris Agreement, but instead requiring a 25 per cent reduction by 2020 over a 1990 baseline.

Plaintiffs ran the table of appellate courts, including a Dutch Supreme Court victory in 2020. There’s been just one hitch. According to a July 2023 study in the Journal of Environmental Law:

If the Urgenda target has been met, this had little to do with the few measures that the government took too late and too hurriedly to achieve genuine [emission] mitigation outcomes. Rather, these measures likely caused a slight increase in global long-term emissions. And while the case has raised awareness, there is no reason to assume that it has translated into momentum for climate action more than it has hindered new policy developments.

Gerrard cautioned: “There’s a lot of energy and activity going into these actions, but it’s too early to say whether it moves the needle.”

US plaintiffs plead for climate action

With 2023 “virtually certain” to be the warmest year on record, and humanity likely living through the hottest 12 months in at least 125,000 years — generating increasingly disastrous impacts — environmental plaintiffs continue to play the long-game of seeking legal remedies where political will is absent.

In August, a group of young people in the US state of Montana won what is described as a “landmark lawsuit” in Held vs. Montana, the first trial of its kind in the United States. There, a judge ruled that the state violated its own constitution by failing to consider climate change when approving fossil fuel projects.

The state constitution guarantees current and future residents “the right to a clean and healthful environment.” Montana, a major coal and gas-producing state, gets a third of its energy from burning coal.

The state is appealing the ruling to the Montana Supreme Court, which previously declined requests to block the case from going to trial. If the plaintiffs prevail, there remains the issue of enforcement. More significantly, a winning decision there would only apply to Montana, with its tiny population of 1.1 million.

California, however, is another matter. With nearly 40 million people, the state ranks as the world’s fifth-largest economy. Its government has set strict vehicle emission restrictions, appliance efficiency standards and electric vehicle sales quotas that ripple throughout the US economy, influencing other states to follow.

In September, its attorney general filed suit in California Superior Court, accusing five of the world’s largest oil companies and their subsidiaries, along with the American Petroleum Institute (the industry’s top trade association), of purposely and persistently misleading the public about the dangers of burning fossil fuels. California is the seventh-largest US oil producing state.

California, according to Governor Gavin Newsom, has endured “decades of damage and deception,” even as fossil fuel companies made huge profits. “Wildfires wiping out entire communities, toxic smoke clogging our air, deadly heat waves, record-breaking droughts parching our wells. California taxpayers shouldn’t have to foot the bill.”

On December 10, the nonprofit law firm behind the Montana case, Our Children’s Trust, filed a lawsuit against the federal government and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on behalf of 18 children from California between the ages of 8 and 17. The suit launched in federal court alleges the government and EPA “intentionally” allowed dangerous levels of fossil fuel emissions in the atmosphere, thus risking the plaintiffs’ health and welfare. In response, EPA said the Biden Administration is committed to reducing the pollution driving climate change.

Elsewhere in the US, climate cases continue to mount. While a federal district court recently rejected environmentalists’ efforts to block Conoco’s controversial Willow Project to drill for oil and gas on Alaska’s North Slope, a federal judge in Oregon ruled in June that a stalled lawsuit brought by Oregon-based climate activists can proceed to trial against the federal government for allegedly violating the US Constitution due to its energy policies, which harm American citizens.

Similarly, Hawaii’s Supreme Court just cleared the way for plaintiffs to hold oil and gas companies liable for their failure to warn that state’s citizens of the climate impacts of their products.

Laura Clarke is CEO of ClientEarth in London, an NGO that tracks and supports climate-related litigation around the globe. She told Mongabay there are thousands of climate lawsuits underway — a symptom of failed government regulation and poor enforcement throughout the developed world.

“Many citizens, groups like ours and even public administrations, are turning to litigation as a way of driving climate action and holding corporations and governments to account for their failure to act,” Clarke said. “Whether it’s environmental law, corporate law, human rights law or international law, these actions have the power to drive systemic change and, once precedent has been set, the same approach can be used time and again.”

Climate change and Indigenous rights

ClientEarth has been working a lot with international law in recent years. In that regard, Clarke said, “We supported a group of eight Torres Strait Islander claimants who lodged a complaint with the UN Human Rights Committee arguing that the Australian government’s inaction on climate change was in violation of their human rights.”

A leading exporter of coal, Australia was found liable by the UN in 2022. The country is now being pressured to compensate the plaintiffs and provide climate change adaptation aid to the islanders, Indigenous peoples who live on low-lying islands that are part of Queensland.

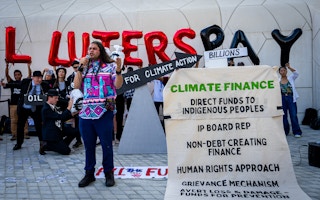

At recent UN climate summits, developed nations have ceremoniously praised the role of Indigenous peoples as being crucial to protecting tropical forests and of enabling nations to meet their carbon emission-reduction targets. But government promises of Indigenous land titles and financial aid frequently go unfulfilled.

Josh Castellino, executive director and professor of law at London-based Minority Rights Group International, told Mongabay that UN promises and pledges “are hugely performative,” and while he says he believes strongly in the power of international law to protect human rights, he often witnesses its limitations.

For more than a decade, his group has participated in legal action on behalf of a Kenyan hunter-gatherer community of some 20,000 called the Ogiek people. The Kenya Forest Service tried to evict the Ogiek from their land in the Mau Forest, but in a series of victories in the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Kenya was ordered to title the disputed land to the Ogiek and compensate them for what was deemed “material and moral prejudice.”

Despite the African court’s 2022 order, Castellino said, the Kenyan government this year, citing forest conservation priorities, is again trying to push the Ogiek from their land.

“The Indigenous peoples we work with have a suspicion of the law,” Castellino said. “They view legal decisions, even those in their favor, with some trepidation. But you work to bring them along. You win, and then nothing happens. We don’t give up. The law is very clear. But the politics of how to implement the law — that’s anyone’s guess.”

Does US law already prohibit fossil fuel burning?

In the United States, partisan politics has brought federal regulatory action on climate change to a halt, with Republicans stopping or reversing legislative efforts pushed by Democrats, which helps explain the scores of climate-related lawsuits across the country.

“It used to be when there was an environmental disaster, it led to legislation,” said Gerrard who pointed out that the Love Canal disaster (a toxic waste site found beneath an upstate New York neighborhood in the 1970s) led to the Superfund Act, and the Exxon Valdez disaster (the massive Alaska oil spill in 1989) led to the Oil Pollution Act. But, he added, the Deepwater Horizon oil well blowout in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 “did not lead to any legislation. We haven’t had new major environmental legislation since 1990.”

Dan Galpern, an Oregon-based environmental and climate attorney, isn’t waiting for new laws. That’s because he feels certain a game-changing law has existed in the US since 1976: the Toxic Substances Control Act, Section 6.

“When people learn about the climate crisis and our nation’s disproportionate responsibility in making it worse,” Galpern told Mongabay, “they think, ‘there ought to be a law.’ In fact, there is a law that is perfectly suited for the purpose of compelling a phaseout of the burning of oil, gas and coal within the United States.”

Galpern knows the act inside and out. Reciting from memory, he said the US Environmental Protection Agency “has the authority to prohibit or limit the manufacture, processing, distribution in commerce, use, or disposal of a chemical if EPA evaluates the risk and concludes that the chemical presents an unreasonable risk to human health or the environment.”

Galpern says he believes fossil fuel emissions — the root cause of climate change — are precisely the kind of chemicals Section 6 allows the EPA to phase out to benefit public health. In support of that view, he noted that the EPA used the act in 1978 to justify the ban of chlorofluorocarbons, the industrial aerosols linked to depleting stratospheric ozone.

Last year, the EPA rejected Galpern’s petition compelling it to act, arguing that it was doing enough under other US laws to reduce carbon emissions. But Galpern is undeterred.

He plans to file a lawsuit in federal court in Oregon in early 2024 that, if successful, could force the world’s most prolific historical emitter of greenhouse gas emissions to oversee a phaseout of fossil fuels within 20 years. That suit is unique among the thousands of lawsuits globally working their way through various courts and jurisdictions in the scale of its potential impact to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“The EPA must take another look at the direct authority it has within its control,” Galpern said. “We don’t have much time. President Biden himself has called climate change an existential crisis. It is. The law is clear. All the science points to an existential crisis that must be addressed aggressively. This is the way to do it. I’ll put it simply: Enforce. Existing. Law.”

This story was published with permission from Mongabay.com.