This is a critical year for climate. All eyes will be on how signatories to the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change are delivering on their commitments at the national, regional, and institutional levels. But while the European Union is rallying its “green deal” and the US presidential election in November will determine its exit or stay in the accord, questions remain over Asia’s commitment.

The war on climate change must be fought on multiple fronts. In Asia, finance may be the most effective weapon. Following in the footsteps of the European and US markets, green finance across Asia has taken off in the last five years. While Asia is too big and too complicated to be generalised, we think the evolution of sustainable finance across the region has a common success factor – regulation.

Regulators have made strong inroads in addressing market failures such as environmental externalities and information asymmetry. Capital flows have responded in kind.

Pricing carbon

China is the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide, responsible for 27 per cent of global greenhouse gases. China’s nationwide Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) aims to cover 8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions annually from around 100,000 industrial plants. The ETS will start with the coal-fired power industry, which is responsible for emitting 3 billion tonnes of carbon per year. The first trade will take place in 2020.

China’s ETS may become the world’s largest market for trading carbon emissions, and could link up with other markets.

Meanwhile, Indonesia has committed to lowering carbon emissions by 29 per cent on its own, and by 41 per cent with international support by 2030. It will pilot carbon trading in 2020 as part of efforts to meet the goals committed to under the Paris treaty. We believe Indonesia has significant potential as a carbon credit generator, by restoring and protecting its priceless natural capital.

“

While Asia is too big and too complicated to be generalised, we think the evolution of sustainable finance across the region has a common success factor – regulation.

Smaller countries are also doing their part. Although Singapore has a relatively tiny carbon footprint with 0.11 per cent of global emissions, the city state has rolled out a carbon tax across all industries. The government will collect the first payment of the carbon tax in 2020 at S$5 (US$3.71) per tonne from facilities that emit 25,000 tonnes or more of greenhouse gases annually. The rate will be reviewed in 2023, with an eye to increasing the tax to between S$10 and S$15 per tonne of emissions by 2030.

Information barriers

Investors around the world have been voicing their need for quality data on environmental, social and governance (ESG). But the data may be inaccurate or missing altogether in Asian companies. Regrettably, years of voluntary disclosure requirements haven’t moved the needle.

Over the last two years, exchanges across Asia have made substantial effort to make ESG disclosures mandatory for listed companies.

China is a case in point. Effective 2020, ESG disclosure will be mandatory for all companies listed in China. Companies will better understand material impacts from ESG factors as more effective measurement and reporting mandates discipline and compliance in the system. The regulation will also significantly improve investors’ ability to assess companies through an ESG-focused lens. Growing international investment in China will further reinforce quality ESG disclosure and ESG risk management.

Similarly, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange recently announced an upgrade of its ESG reporting rules. From July 2020, Hong Kong-listed companies must report the role of the board in ESG governance, disclosure, and materiality in ESG reporting. Companies must also include an assessment of the effects of climate change, disclosure of social key performance indicators, and external assurance for ESG data.

The ultimate goal of all these measures is to influence capital flows towards activities that will support the transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient and sustainable economy.

China’s 13th five-year plan covering 2016-2020 mandated influencing capital flows for sustainable development. With a green financial system that now promotes green credit, green bonds and green funds, credits supporting the green sectors from 21 major Chinese banks reached 10.6 trillion RMB ($1.54 trillion) in the first half of 2019. This represents 9.6 per cent of the banks’ total outstanding loans, an annual compound growth rate of 13.9 per cent compared to the first half of 2013, according to the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission.

Last year, the People’s Bank of China revised its macroprudential assessment to include green lending and green bonds, which encouraged more green financing by banks. China has been the leading green bond player globally since 2016, with total onshore and offshore issuance of 350 billion RMB in 2019, 30 per cent more than in 2018, according to the China Green Finance Committee.

Meanwhile, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority announced a phased approach to promote green and sustainable banking in May 2019. The first phase developed a common framework to assess the “greenness baseline” of individual banks. The second phase set tangible deliverables, and the third mandated implementation, monitoring, and evaluating banks’ progress. Hong Kong also debuted its $1 billion green bond.

Outside Greater China, we witnessed a surge of sustainable bond issuance from South Korea in 2019, including a $500 million sovereign sustainable bond, aimed at supporting the green agenda and social development. Korean companies followed suit, racing to tap ESG capital globally. Korea’s US dollar and euro-denominated sustainable bonds reached a total $9.59 billion last year, almost triple the 2018 issuance, and second only to China.

In Southeast Asia, regulators are walking the talk. The Monetary Authority of Singapore has included banks’ sustainability practices in its supervisory assessment. It has encouraged local banks to adopt industry standards and to enhance ESG disclosure, including completing ESG assessments for their corporate clients.

The Malaysian central bank, meanwhile, seems to take inspiration from the European Union. It has plans for a ‘principle-based’ green taxonomy for banks and insurers to identify and label economic activities that could contribute to climate change objectives.

Indonesia has taken green bonds to its heart with two landmark green sukuk or Islamic bond transactions in 2018 and 2019 respectively, with 27.4 trillion rupiah ($2 billion) outstanding.

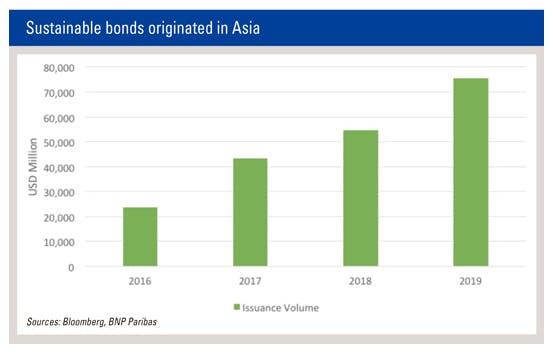

Overall, sustainable bonds originating in Asia grew approximately 48 per cent annually from 2016 to 2019 according to data compiled by Bloomberg, signifying the strong demand and supply dynamic.

Beyond debt

Outside debt markets, ESG investing has positive traction but is still playing catch-up. According to the International Monetary Fund’s latest Global Financial Stability Report, there are nearly 2,000 funds with $850 billion of assets under management investing under ESG strategies. There is a clear gap that Asian-based investors need to close over time.

Asian securities regulators can look to Japan for inspiration. According to the Global Responsible Investment Review, Japan is the third largest market with $2.18 trillion of assets under management embracing a spectrum of ESG investing strategies. Asset owners like the 159.21 trillion yen ($1.45 trillion) Government Pension Investment Fund and insurers such as Japan Post Insurance and Dai-ichi Life are the driving force in making ESG investing mainstream in the country.

It’s clear there is more work to do in Hong Kong. The Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) recently conducted a survey to determine how licensed asset managers regard ESG factors and climate risks in their investment decisions. Only 35 per cent of the 660 licensed asset managers surveyed consistently integrated ESG factors in their investment and risk management processes. And just 23 per cent had processes in place to manage the financial impact of risks arising from climate change.

Despite Hong Kong’s position as an internationally recognised financial centre, there are only around 20 ESG thematic funds available in in the city. A circular from the SFC at the end of 2019 sent a clear message to funds that more effort is required on ESG integration. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority, which manages a HK$4 trillion ($510 billion) Exchange Fund, has publicly committed to ESG investing and recently became a signatory to the United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Investment.

In Southeast Asia, the Monetary Authority of Singapore set up a US$2 billion green investments programme to accelerate the growth of a green finance ecosystem in the city state. In Malaysia, the country’s securities regulator introduced guidelines on sustainable and responsible investment funds in 2017, providing detailed information about sustainable and responsible investment policies.

2020 resolutions

This is going to be a make or break year for climate policies, with countries coming back to reassess their national determined contributions under the Paris accord. Asian countries must continue making headway in the global fight against climate change, and their financing policies are a critical piece of the puzzle.

Policymakers should continue to take the leadership role in paving the way as green bond issuers and ESG investors to spur greater private sector participation. Asia currently has three sovereign green bond issuers – Indonesia, Korea and Hong Kong. But there are 51 countries or regions, encompassing 60 per cent of the global population, which have yet to tap green financing to fund their climate transition.

Bain & Company estimates that 90 per cent of Asian investors have accelerated their effort to invest sustainably over the past three to five years. Between 2018 and 2019, the number of Asian fund managers that have signed up to the Principles of Responsible Investment increased by 15 per cent.

This is promising news because the task ahead is immense. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that the world would have to cut global greenhouse gas emissions by a whopping 45 per cent from 2010 levels by 2030 in order to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius this century.

To reach these targets, we will need to mobilise trillions of dollars of capital from all public and private sectors and fund a sustainable transformation across Asia.

Dr MA Jun is chairman and president of the Hong Kong Green Finance Association (HKGFA) and chairman of the China Green Finance Committee.

Chaoni Huang is vice president of HKGFA and executive director, head of sustainable capital markets Asia Pacific at BNP Paribas.

This article was originally published in Asia Asset Management.