A vast pool of dark green water, about the size of a football field, sits roughly 25 meters from Elementary School 033 in the Loh Iput Darat district in Kutai Kartanegara, East Kalimantan.

The only barrier between the school and this pond is a rusty wire fence, broken in several places.

“Pit 2 belongs to PT MHU,” proclaims a red-painted sign board, indicating this pool has formed in a hole excavated and then left behind by the coal-mining company PT Multi Harapan Utama. There are no other warnings posted, let alone a guard, despite its proximity to a settlement and a school full of young children.

Indonesia’s environmental regulations clearly state that mines should not be excavated within 500 meters of houses. Investigations in mining areas in East Kalimantan found multiple pits in clear violation of this law.

A case from the same district sharply illustrates the dangers of having abandoned mines and children in close proximity. In December 2015, a schoolboy named Mulyadi drowned in a similar pit, also owned by PT MHU. On the day Mulyadi died, this pit was left without any guard on duty. Although the pit is only about 300 meters from the nearest house, there was no barrier and no sign banning entry.

The company only installed a sign and a fence the day after East Kalimantan Governor Awang Faroek Ishak issued a December 18, 2015 decree freezing the operations of 11 coal mining companies, including PT MHU.

In his decree, Ishak stated 11 companies violated rules by, among other things, not “reclaiming” and “revegetating” their mining sites— technical terms for refilling pits and reforesting the land. The companies were also considered neglectful for not supervising the pits they left behind.

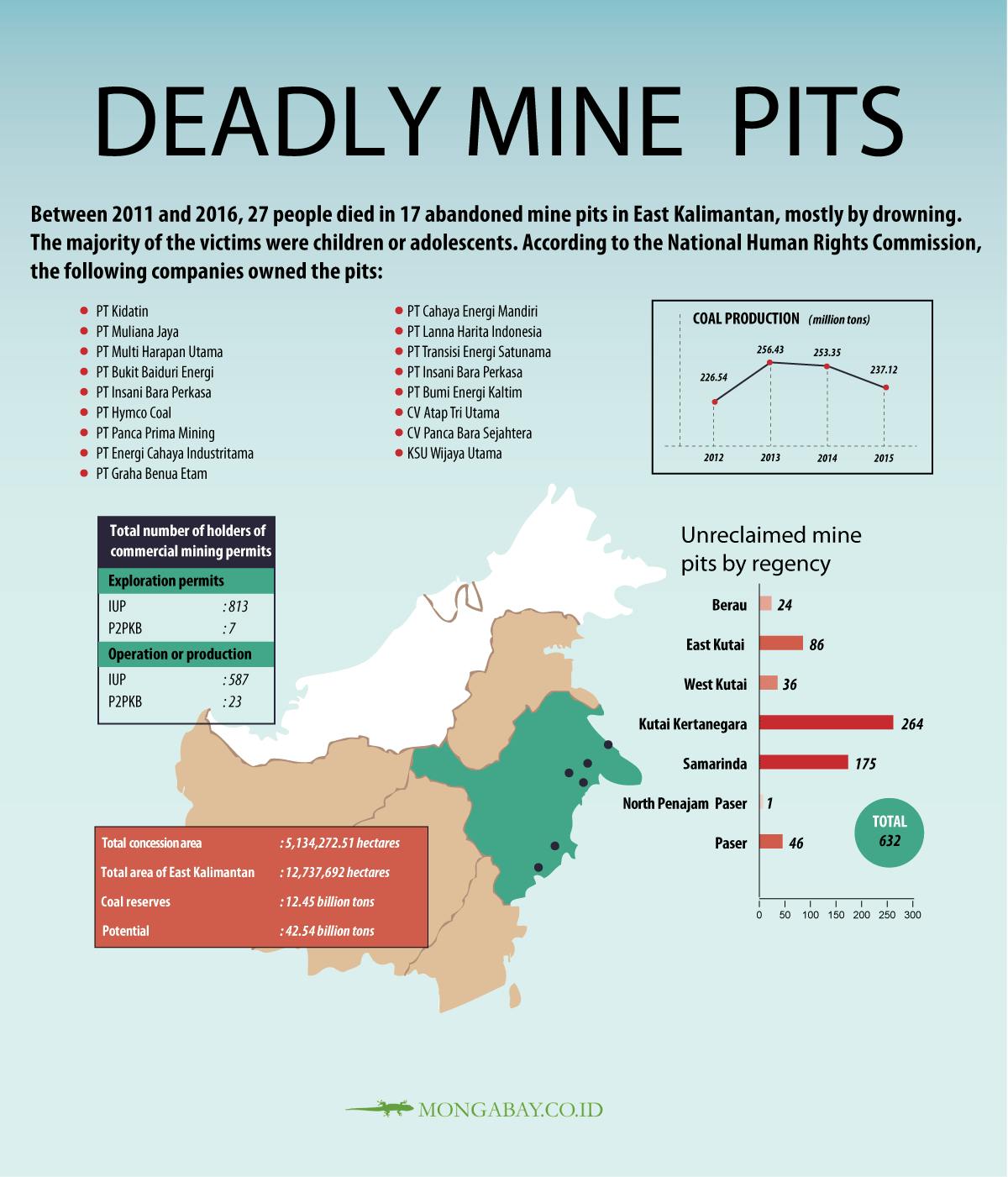

Suspending permits did not stop mine pits from claiming more victims. The National Commission on Human Rights found that mine pits left behind by 17 companies in East Kalimantan killed 27 people between 2011 and 2016, mostly children or teenagers.

East Kalimantan’s black gold

According to data from the Office of Mines and Energy, there are 1,430 mining permit holders in East Kalimantan Province — 820 companies holding exploration permits, and the rest given permission to operate. Altogether, these companies hold concessions covering 5.13 million hectares (12.7 million acres), just over 40 per cent of the province’s total land area.

In 2015, these companies extracted 237.12 million tonnes of coal from the province, amounting to almost half of the total national production of 461.6 million tonnes.

“

Of course there will be mine pits. But they will gradually be restored with soil removed from the next mining area.

Tri Harjono, spokesperson, PT Indo Tambangraya Megah

Coal production is now predicted to decline, in part due to sluggish demand from India and China. According to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resource’s strategic plan, nationwide coal production in 2019 is predicted to drop to 400 million tonnes.

As a result, many coal mining companies have gone out of business. In 2015 alone, 125 mining companies in East Kalimantan went bankrupt, many of them leaving behind unreclaimed mine pits in their concession areas.

The true scale of the problem is difficult to determine. Amrullah, head of the East Kalimantan Office of Mines and Energy said reports from 81 companies indicated there were a total of 314 former mine pits in the province as of December 2016. However, a survey conducted by the Office counted more than twice that number by using Landsat images to spot 632 coal mines transformed into giant puddles.

The true number could be even higher. Not all pits are visible on satellite images, due to factors like cloud cover at the time images are captured. In addition, Amrullah said many companies still have not reported their mining pits, and the Office of Mines has not made direct field inspections.

Text: Anton Septian/Tempo. Data: East Kalimantan Office of Mines and Energy, Directorate General of Legal Administration of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights.

The names behind the companies

According to data from the East Kalimantan Office of Mines and Energy, PT MHU holds 47,230 hectares of concessions and has left 56 pits scattered across Kutai Kartenegara. The real number is likely to be higher. For example, when visiting a site in Jonggon Jaya Village in Kutai Kartenegara where records show just one pit, Mongabay-Indonesia found two, both without fences or posted registration numbers.

Based on the latest company documents obtained by Mongabay-Indonesia, PT MHU is owned by PT Pakarti Putra Sang Fajar and Private Resources Pty Ltd. In turn, PT Pakarti’s shares are owned not by individuals but by two other companies: Bhaskara Alam and Riznor Rezwara.

These companies are linked by one name: Reza Pribadi. He is listed as a commissioner of both PT MHU and PT Pakarti. At PT Riznor, he is listed as a shareholder along with Rizal Risjad.

Pribadi is also listed as director of PT Riznor, a position he also holds at Private Resources — “private” can be translated into Indonesian as “pribadi” — a company headquartered in Perth, Australia. Reza Pribadi is the son of Henry Pribadi, owner of the Napan Group, one of Indonesia’s largest companies.

PT MHU did not respond to repeated requests for comment in person, by mail or by email.

Other well-connected companies have also left behind mining pits in East Kalimantan.

PT Energi Cahaya Industritama’s former mine is located in Rawa Makmur, in Samarinda. An 11-year-old named Nadia Zaskia Putri died in that pit on April 8, 2014. The company reported just five pits of the Office of Mines. Based on satellite imagery, the company appears to have left behind 22. A subsidiary, PT Dunia Usaha Maju, left behind two more pits in Samarinda, bringing the total to 24.

Budi Fachroni, head of technical mining at PT Energi Cahaya Industritama confirmed the company has left behind coal-mining pits, but said the number was much lower. He said 11 holes have already been closed, three are in the process of being reclaimed and another six are still being actively mined.

In this company, there are two retired two-star police generals, Aryanto Sutadi and Alpiner Sinaga, whose roles are listed as “first director” and commissioner.

At least one company has left behind even more mine pits than PT MHU. Data from the mining office suggests that a company called PT Kaltim Prima Coal has left behind 71 open pits in East Kutai regency, although the company states it has only 29 inactive mine pits.

According to Imanuel Manege, PT Kaltim Prima Coal’s general manager for health, safety and the environment, 11 of those pits are currently being mined, 18 have not been excavated, while eight have already been reclaimed. “We close the pits in accordance with the mining plan approved by the Directorate General of Minerals and Coal,” said Manage.

So far, there have been no reports of deaths in any of these sites.

PT Kaltim Prima Coal is owned by the PT Bumi Resources holding company, one of Indonesia’s largest coal producers. The majority owner of PT Bumi is the Bakrie Group, a massive conglomerate owned by a powerful family that includes Aburizal Bakrie, a former cabinet minister who also served as chair of the Golkar Party.

There is also PT Indo Tambang Raya Megah. This company is believed to have 68 coal mining pits through three subsidiaries: PT Trubaindo (20 pits), PT Kitadin Embalut (14) and PT Indomunco Mandiri (34). PT Indo Tambang Raya Mega is a subsidiary of Thai mining firm Banpu Public Company Ltd.

PT Indo Tambangraya Megah spokesperson Tri Harjono said the group has not yet filled in these pits because the mines are still active. “Of course there will be mine pits,” said Harjono. “But they will gradually be restored with soil removed from the next mining area.”

This story was published with permission from Mongabay.com. Read the full story.