Are fossil fuel industry representatives a necessary part of global climate change negotiations, or does their presence at these talks represent a conflict of interest and undermine global progress?

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

This question, which has been brewing in United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) discussions since last year, reached a critical point at ongoing talks in Bonn, Germany on Wednesday 9 May when the UNFCCC secretariat agreed to enhance the “openness and transparency” of the talks, and accept suggestions on how it can do so.

The move comes after months of heated debate between countries about the appropriateness of allowing fossil fuel lobbyists and representatives to participate in the talks. While companies cannot participate in the talks as independent entities, membership-based business and industry non-government associations (BINGOs) can.

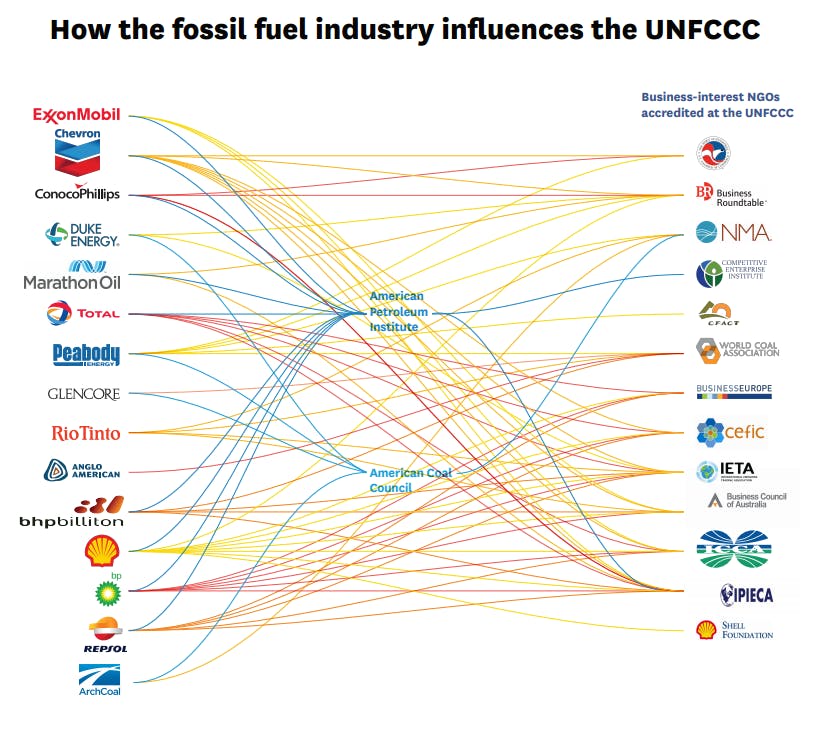

And as a recent report by Boston-based non-profit Corporate Accountability International (CAI) explains, fossil fuel representatives are extensively represented in the associations that participate in the UN climate talks. Examples of such organisations include the National Mining Association, FuelsEurope, the World Coal Association, and the Business Council of Australia. The latter’s members include Shell, ExxonMobil, and BP.

A Corporate Accountability International chart showing the links between fossil fuel companies and business NGOs, all of which are admitted to the UNFCCC negotiations. Image: Corporate Accountability International

CAI notes that industry representatives not only weaken climate action efforts by speaking out in the UNFCCC negotiations that they are allowed to attend, but their presence at the talks also gives them easy access to global leaders.

As Tamar Lawrence-Samuels, international policy director, CAI said in a statement: “With so many arsonists in the fire department, it’s no wonder we’ve failed to put the fire out.”

Developing nations have broadly echoed this view, with countries such as Uganda, Ecuador and the Philippines arguing that organisations such as the business associations, which have observer status, should be open and transparent about any conflicts of interests. This would pave the way to limiting the presence of the fossil fuel industry at the talks.

“

With so many arsonists in the fire department, it’s no wonder we’ve failed to put the fire out.

Tamar Lawrence-Samuels, international policy director, Corporate Accountability International

But wealthy countries with large fossil fuel industries, such as Norway and Australia, have opposed such calls.

For instance, at a panel discussion during the Bonn talks on May 9, which focused on how to enhance the engagement of “non-party stakeholders”—UN jargon for non-government actors like NGOs and UN agencies—representatives from the two countries shot down a suggestion from an audience member that these conflicts should be declared.

A representative from the World Health Organisation’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, pointed out that the global treaty has only been successful in tackling the global tobacco academic because it recognised that tobacco companies spent years trying to undercut public health policy and campaigns to combat theglobal rise in tobacco use.

“In limiting the role of the tobacco industry in fighting the problem that it has itself been responsible for, helps to limit the power that it has to continue to cause the problem,” she said. “Within the context of the UNFCCC perhaps this means limiting the role of corporations that drive the climate crisis that the convention aims to stop.”

In response, Norway said that excluding companies based on their interests would be “counterproductive”, while Australia’s energy ambassador for the environment and delegation head Patrick Suckling said that private sector money was a key part of financing the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Suckling added: “Business is driving the technology and investment in the transformation in a fundamental and significant way, including some of the companies that were being alluded to as the polluters of policy.”

“Some of these companies will be the providers of the biggest and best solutions, so let’s not cut off our noses to spite our faces,” he said. “They play a very fundamental and important role…You could look at some of the statements coming out of ExxonMobil and Shell to underline that point.”

In the past two years, it has emerged that both ExxonMobil and Shell knew about the impact of burning fossil fuels on climate change for many decades, but suppressed the information.

Australia’s remarks were met by swift criticism from environmentalists, with Greenpeace Australia Pacific chief executive David Ritter calling the speech a “new low”.

“It is outrageous and disgusting to imagine representatives of the Australian government would defend such a flagrant conflict of interest,” said Ritter in a statement.

“But it shows the kind of hold that fossil fuel companies have had on Australian politics for too long.”

Ritter added that the Australian government should be calling for the same standards of fairness that govern the country’s public service. “Principles behind conflict of interest rules are well-known and universal and we should be striving to uphold them,” he noted.

CAI’s Lawrence-Samuels, in a press conference after the panel discussion, said that the session places the conflict of interest question squarely on the table, and forces parties to confront the issue.

“There’s no longer any way for parties to ignore or avoid this issue,” she said. “A robust and evidence-based policy will be central to the creation of the Paris rulebook.”

Intervention of fossil fuel interests has hampered a low-carbon energy transition for more than two decades, said Lawrence-Samuels. Clear rules to avoid conflict of interest “is what is needed to ensure that we are taking action on climate change,” she said.

The UNFCCC is accepting suggestions on how to address the issue from member nations, and aims to take them up next year.