The renewable energy revolution is on an explosive growth path from China to India to Latin America, but it appears to have not yet properly reached the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), a regional grouping of 10 countries with a combined population of 640 million people.

Let’s get the bad news out of the way first.

Singapore — the only first-world country in the region and one that should be leading by example — remains disappointingly in denial of the potential of solar power and electric vehicles, with hardly any deployment at all. Indonesia — a nation extremely suitable for solar and wind across its 17,000 islands — continues to import diesel in polluting vessels rather than seek the energy independence, security, and cost savings that are possible with renewable energy.

Thailand’s new administration has put an almost complete stop to the expansion of renewable energy in the country while Vietnam continues to talk solar while pushing coal. Malaysia distinguishes itself globally as the only country where the number of solar panel installations has actually declined in recent years.

“

The resistance to renewable energy in the ASEAN region can’t last: The clean energy revolution is poised to steamroll fossil fuels worldwide as the cost of renewables plunges.

All in all, Asean is the worst-performing region globally in terms of renewable energy deployment and transport sector electrification. One notable exception is the Philippines’ laudable efforts to introduce renewable performance standards that, while in their infancy, will make a difference if enforced.

Excuses abound to defend the status quo.

Nations still buy into debunked myths such as privileging coal as a solution to energy poverty, despite the superiority of distributed solar systems and coal’s track record of leaving the poor in its wake (some 1.2 billion people around the world still lack access to electricity).

Other nations perpetuate the status quo through regulation. For example, officials in Singapore treat electric vehicles the same as gas guzzlers from a regulatory perspective. Powerful fossil fuel lobbies across the Asean region are also hindering progress.

Asean member countries

Now the good news

The resistance to renewable energy in the Asean region can’t last: The clean energy revolution is poised to steamroll fossil fuels worldwide as the cost of renewables plunges. Most recently, a solar contract in Nevada set a new record of about 2 cents a kilowatt hour — a price so low that forecasters thought it wouldn’t be reached until 2050.

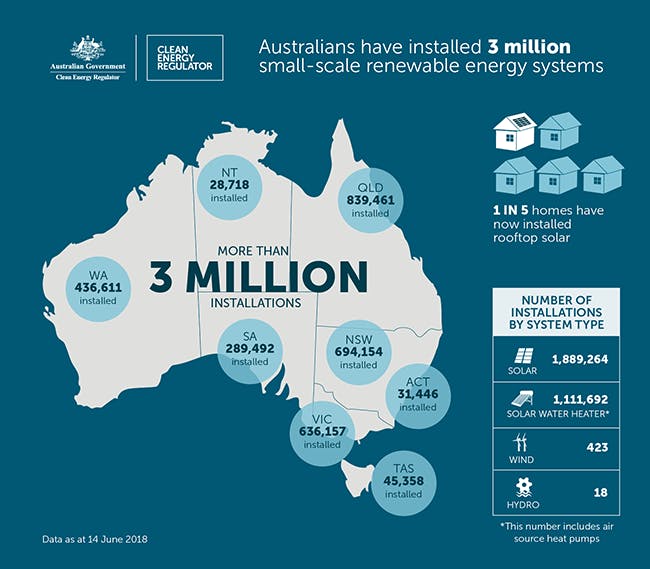

Closer to the Asean region, Australia’s small-scale renewable energy systems passed the three million-milestone this June. Rooftop solar accounts for 63 per cent of all installations encouraged through the country’s Small-scale Renewable Energy Scheme, which creates a financial incentive for individuals and small businesses to install eligible small-scale renewable energy systems.

All of this is in spite of the government’s overarching climate and energy policy — a do-nothing approach with continued support for coal and lignite.

There is little Asean can do to resist powerful global trends. A region where power generation is expected to double by 2025 while overall energy demand grows by 50 per cent cannot continue to so thoroughly ignore renewable energy.

First, utility-scale solar and onshore wind are already competitive with fossil-fuel electricity in Asean without any subsidies whatsoever — a fact too-often overlooked by politicians and regulators. Current barriers to deployment at scale are artificial rather than market-based (for example, resistance by politicians and grid operators). This is true without even taking into account the health, environmental and pollution advantages of renewable energy over coal, oil and gas.

Second, as Abraham Lincoln said: “You can fool all the people some of the time and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time.” While coal-fired power is losing ground everywhere else, Asean seeks to increase its reliance on coal to fulfill its energy demand. Abundant local coal reserves in Asean countries such as Indonesia lead politicians to argue that providing energy from coal is the least costly option compared to other sources.

This is false on several accounts.

Coal-fired power is already more expensive than utility-scale solar in all Asean countries and benefits from deep and broad embedded subsidies — notwithstanding propaganda to the contrary. Renewables can also be deployed much faster than coal and gas-fired power (months rather than years) and their distributed, decentralised nature saves billions in grid upgrade costs.

IRENA, an intergovernmental organisation, estimates that external costs related to air pollution from the combustion of fossil fuels in Asean are already running at a clip of $167 billion per year and will increase by 35 per cent to $225 billion in 2025. That’s before the climate change footprint of Asean’s energy consumption is taken into account.

It is shameful that politicians disregard the environmental and health impacts of coal and gas-fired power generation on their own population, not to mention the fumes from car, bus and two-wheeler fleets. The people, however, are well aware of the damage inflicted by coal and gas: local communities are rising up whenever a coal-fired power plant is proposed near them and protests against coal have been prominent in Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar.

The role of technological innovation

KIUC’s Tesla solar-plus-battery facility.

While even adoption of more basic renewable energy technology would have an enormous impact on the future of Asean’s consumption and regeneration, there are some new technologies that are particularly well suited to accelerate the region’s progress.

For example, renewables-plus-storage systems can cost-efficiently turn many of the inhabited islands of Indonesia and the Philippines into 100-per cent renewables zones. We are watching this goal currently being achieved at the Lāwa’i Solar and Energy Storage Project on the Hawaii island of Kauai.

The 28 MW solar and 100 MWh five-hour duration battery energy storage system will provide electricity for under $0.11 per kilowatt-hour, which is significantly below the cost of diesel generation and represents large savings for islands dependent on expensive polluting fuel. It also spares the population of toxic fumes.

Meanwhile, a new solar panel recently went to market that uses its electricity to draw water from the atmosphere to deliver up to 5 liters of pure water per day — a potential life-saver for many in the Asean region. The technology developed by ZeroMassWater also offsets 70,000 plastic water bottles throughout its lifetime and covers its costs in just five years.

Innovation around mobile solar technology could also have implications for Asean, making it possible to deliver a much larger power capacity to affected areas.

Flexible solar panels designed by Renovagen unroll like a carpet and are ideal for disaster relief especially in a region at the forefront of suffering from climate change. The Rapid Roll system is currently being used to help power an island off the coast of Cardiff.

Innovation powered by financing and people

External and internal pressure is mounting on Asean countries to join the renewable energy revolution and adopt innovative solutions rolling-out worldwide. This is partly because the Asean region can’t continue to ignore climate change for much longer: After all, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam are routinely ranked among the top 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change. In addition, international capital markets have been putting their foot down lately, with finance being redirected in a positive direction by pension funds no longer prepared to finance coal-fired power and eager to finance renewables.

Climate change, ethical finance and people power are bound to force Asean to turn the corner on renewables and adopt global environmental technology innovations that allow its citizens to live healthier lives fuelled by clean energy.

Assaad Razzouk is the CEO of renewable energy firm Sindicatum and sits on the board of Eco-Business. This article was first published on Medium and is republished with permission.