An array of solar panels floats on the waters of San Antonio in San Pedro, one of the cities surrounding Laguna de Bay, the Philippines’ largest freshwater lake 55 kilometres south of Metro Manila, on the northern island of Luzon.

Installed in March by renewable energy firms SunAsia Energy and Ciel et Terre, the 13 kilowatt structure is a year-long experiment to see if the photovoltaic (PV) panels can withstand the strong waves and gusty winds at the lake.

In the nine months since it was installed, the test bed has survived more than 10 typhoons that have slammed into Luzon, said Karlo Abril, SunAsia’s floating solar project lead. They included Typhoon Mitag—the most powerful typhoon in the country this year with a wind speed of up to 170 kilometres per hour, and which also caused fatalities in Japan, China and South Korea.

Screw piles used to anchor the aluminium frame modules in the solar PV test bed in Laguna de Bay. Image: SunAsia Energy Inc

Aware of the 911-square-kilometre lake’s exposure to extreme weather, developers have used a screw piling method for the modules carrying the solar panels, to allow them to move more freely in waves.

Apart from the anchors, installers have attached recyclable polyethylene frames that cradle the solar panels and are able to withstand winds of up to 118 miles per hour.

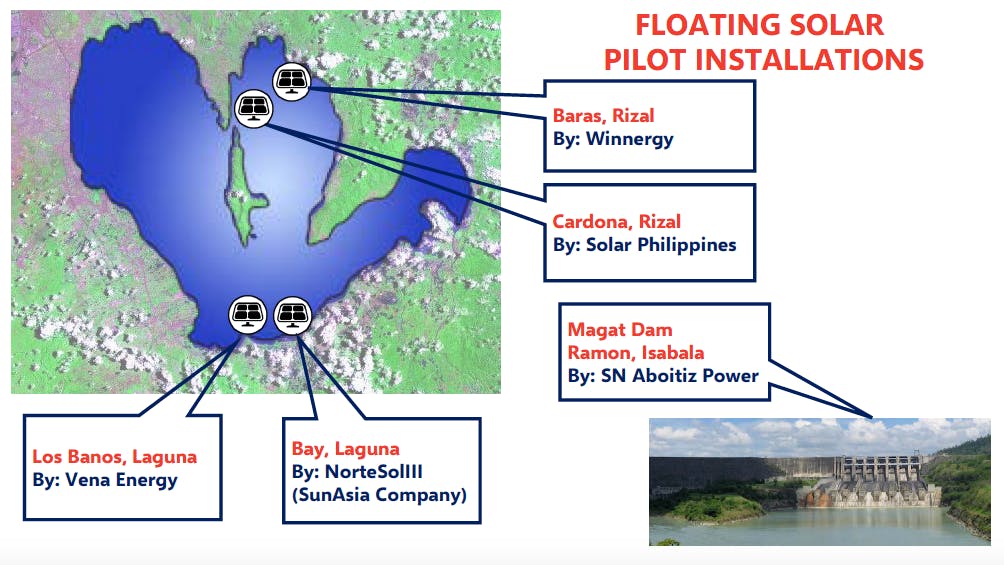

The San Antonio test bed is one of the five floating solar pilot installations in the Philippines, mostly set up in the waters of Laguna de Bay.

Solar energy companies in the Philippines have started turning to lakes and dams to install solar arrays as part of the government’s wider push for 2,000 megawatts in installed capacity of renewable energy in 10 years.

Abril fancies the potential of floating solar in the Philippines, an archipelago of more than 7,100 islands, with over 200,000 hectares of lakes and 19,000 hectares of water reservoirs.

“The Philippines has a potential of 11 gigawatts of inland floating solar if it covers just 5 per cent of the country’s water surface, which can power up to 7.2 million households,” he told Eco-Business. “Offshore floating solar may be the solution for islands with limited available land areas. “

Embracing its vulnerability to typhoons

If solar arrays can withstand conditions in a country that is hit by an average of 20 typhoons per year, the technology can survive less treacherous conditions in other countries, said Dr Thomas Reindl, deputy chief executive of the Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore.

SERIS deputy chief executive officer Thomas Reindl speaking at the 4th ASEAN Solar + Energy Storage Congress in Muntinlupa City, Philippines. Image: ASES

“Most floating solar projects I’ve seen are done in calm waters as it’s the easiest way of deploying them. Very few countries have floating solar deployed right away in strong winds like the Philippines,” Reindl told Eco-Business on the sidelines of a floating solar conference at Muntinlupa City in the Philippines this month.

“The Philippines should embrace being prone to typhoons and use the situation as a source of knowledge for research to develop solutions and sell the expertise to other countries which also have strong winds, like Japan, Taiwan and South Pacific Islands.”

In Japan and Taiwan, floating solar systems typically use steel or concrete structures to be typhoon-safe, but they are “10 times more expensive than the plastic floaters being used for floating solar technology”, said Reindl.

“The Philippines’ competitive advantage would be to come up with a solution that would work with strong winds and is, at the same time, cost-effective,” he said.

“

The Philippines should embrace being prone to typhoons and use the situation as a source of knowledge for research to develop solutions and sell the expertise to other countries which also have strong winds, like Japan, Taiwan and South Pacific Islands.

Thomas Reindl, deputy chief executive officer, Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore

Water surface rights and more tests needed

Despite the resilience of the San Antonio test bed in Laguna de Bay, largescale installation—project developers are targeting 110MWp—has yet to be approved. Just like the four other pilots in the country, it is still pending the go-ahead from regulators because there are no clear rules on water surface rights, SunAsia’s Abril said.

“[Floating solar panel technology] is something new to regulators. With land, you have land rights, but how can you define water surface rights? You’re not using the flow of water, you’re not drawing water, but you’re just on top of water. It’s a matter of defining property rights over water surface area,” Abril said.

Solar energy firms also need to prove to regulators that the floating PV systems are not harmful to marine life, especially in a town like San Antonio, where fishing is a major source of livelihood for the residents along the lake, said Abril.

There is no on-site report yet that shows how the test beds affect fish supply in Laguna lake, but Abril cited a 2018 study by the Asian Development Bank that found Vietnam’s first floating solar power plant at a reservoir in Binh Thuan province had “no impacts to natural habitat”, including fish supply.

Solar panels can improve environmental conditions by blocking sunlight from penetrating the water, Abril claimed. This reduces evaporation and inhibits algae blooms which may be toxic for people and marine life.

The structure also does not affect water quality of the lake, which provides 4 per cent of Metro Manila’s water supply, he said.

In spite of solar energy firms’ claims about the lack of impact on biodiversity, regulators are taking a “precautionary stance”.

While excited about the technology, the Laguna Lake Development Authority is still conducting tests, said Adelina Santos-Borja, its department manager under the Resource Management and Development Department.

“We are dealing with uncertainties, that’s why we have to take baby steps. We will have high socio-economic problems if we don’t, because it is a multi-use lake. It’s used for drinking water and (is) also a transport route for fishermen and relied on for their livelihood,” Santos-Borja told Eco-Business.

Borja said the regulatory body is still conducting tests and does not have enough data for the pilot projects to be approved on a large-scale basis.

“We just have to wait for all pilot tests to end, with the last one to finish on August 2020. From these tests, we will generate science-based analysis before crafting policy,” she said.

There are four floating solar test beds in Laguna de Bay, and one in a dam in Isabela province also in Luzon. Image: SunAsia Energy

Jobs and lower electricity costs

An expansion of the test beds to 10 per cent of the lake would generate jobs for residents and help reduce their electricity expenses, Ciel et Terre and locals said.

Ferdinand Toga has been fishing for more than 30 years, like most of the residents in the fisherfolk town of San Antonio, Laguna. Image: Eco-Business

“Even at 10 per cent, that’s already a little bit over 9,000 hectares. One hectare is equivalent to one megawatt so that translates to 9,000 megawatts of renewable energy for the town,” Ciel et Terre’s Philippine lead Raymond Rodrigo told Eco-Business.

The system will need to be cleaned and maintained, and security guards will also be needed at the power plant, he said.

The pilot projects around Laguna de Bay have already powered streetlights, a museum, a police station, a daycare centre and community halls.

San Antonio resident Ferdinand Toga, 52, and his neighbours have seen the town’s pilot project power five air-conditioning units at the town hall.

Toga, a fisherman and father of three who earns US$6 to US$20 a day, said: “We hope the solar panel project will be approved so that it will help mimimise our electricity expenses, just like it has done (for) the barangay hall.”